Otaku Meaning

What is an otaku? In Western anime fandom, otaku is used interchangeably with anime fan(s), but that's not quite what it means in Japan. While anime - particularly late-night shows aimed at less mainstream audiences - are often associated with otaku, an otaku is not necessarily an anime fan.

An otaku is an obsessive fan of any topic. Obsessive being the key word here. It's not the same implication as geek or nerd in the West, as over the past 30 years or so, geeks have achieved a high level of acceptance, whereas otaku is more pejorative.

The linguistic term originates from an overly polite form of "you", 'お宅', literally meaning "your house", the implication being that those labeled as otaku are socially awkward and often prefer to stay at home. There are growing numbers of self-identified otaku in Japan, though usually it's fandom-specific labels such as anime otaku or game otaku that get worn with pride rather than just the general term otaku, which is still usually something of an insult. The phrase was popularized or even possibly coined by Akio Nakamori in a series of essays about otaku in the hentai anime magazine Burikko. You can check out an English version of his introduction to otaku here.

What is the Meaning of Fujoshi?

Fujoshi is a term that refers to specifically female otaku. The term is a combination of 腐 (fu), meaning "rotten", and 女子 (joshi), meaning "girl". While female otaku can also simply be called otaku as well, they can also be referred to as fujoshi. Being an anime fujoshi often implies certain things about the female otaku's interests: common niche fandoms for fujoshi include gothic lolita fashion as well as yaoi, explicit anime, manga, or games about love (or lust) between boys or men.

Fujoshi have become a growing market, though there are way less anime explicitly for and about fujoshi. Lucky Star, despite its all-female cast, was a shounen series (the doujin artist Hiyori Tamura is closer to the standard fujoshi archetype than Konata, who's more idealized to male otaku tastes). Genshiken remains seinen but its most recent series Genshiken Nidiame increased the number of female club members, continuing to present the broad scope of Japanese fandom. The best josei series about female otaku, and one of the best about otaku in general, would have to be Princess Jellyfish. While the main characters work as assistants to a reclusive Boys Love manga artist (the most stereotypical fujoshi profession), their special interests go beyond the expected manga/anime gaming otaku interests into more specific and unusual areas of obsession, including dolls, old men, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, model trains, and, yes, jellyfish. Humorous yet empathetic, there's sadly no second season, but the manga is being translated on Crunchyroll and finally being published in print on March 22nd.

Men who also enjoy Boys Love, not to worry. There is another term, fudanshi, that refers to otaku boys with those specific interests.

How are Anime Fans or Anime Otaku Viewed by Society?

Otaku, and some of the individual fandoms associated with anime fans, got a particularly bad rap following the 1989 arrest of Tsutomu Miyazaki, a pedophile and serial killer who unfortunately happened to have an extensive collection of anime and horror film VHS tapes. In the aftermath of that case, it was an anime OAV, Otaku no Video, that began to rehabilitate the image of otaku.

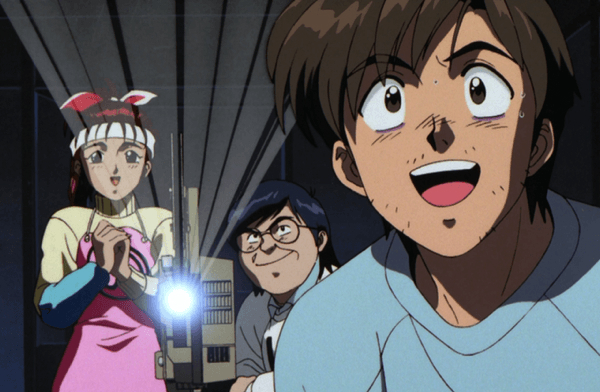

The main story focuses on once normal-seeming boy Ken Kubo who reluctantly falls in with the otaku crowd and over the years takes otaku obsession to the next level, starting multiple business ventures and vowing to become the "Otaking, King of Otaku." It's a story heavily inspired by the origins of the OAV's animation studio Gainax, which started as a few hardcore anime fans making their own anime videos for conventions. Very much a film made inside the otaku culture, it both mocks and celebrates it. Interspersed between the animated story bits are live-action documentary interviews with various anime fans, which serve as a fascinating and sometimes awkward sociological study of early '90s otaku culture. The interviewees range from a successful businessman who talks about being into the anime fandom as a past phase to a few genuinely unhealthy cel thieves and hentai obsessives, and a wide range of anime fans in-between the extremes.

The Anime Otaku Community Just Keeps Growing and Growing and Growing...

By the turn of the century, otaku were a growing subculture, and an economically powerful one at that. Akihabara, the popular electronics district in Tokyo, had become an otaku haven, filled with cosplay, maid cafes, and shops selling anime goods of all kinds. The "Cool Japan" campaign, started in 2002, emphasized pop culture and technology, areas of common otaku interest, as a significant form of Japanese cultural power internationally.

The 2004 novel Densha Otoko (Train Man), allegedly based on a true story from a 2chan message board thread about a shy otaku who defends a girl being harassed on a train and eventually ends up dating her, became a massive hit and further served to lessen the negative stigma against otaku. Making shows for otaku was a safe bet for animation studios, and an increasing number of these shows were about otaku too.

Genshiken followed the adventures of a joint anime/manga gaming club with a wide range of characters from the surprisingly fashionable Makoto Kousaka to the pervy over-the-top Manabu Kuchiki. Relatable for otaku, occasionally in an uncomfortable way, the series received multiple seasons. Less realistic is The World God Only Knows, a series in which the main joke is that an anti-social dating sim otaku is actually able to use his gaming skills and a bit of magic to effectively romance real women. It too received sequels.

Perhaps Japan's biggest hit in the "for the otaku by the otaku" genre was Lucky Star, a comedy series filled with anime in-jokes that's main character, the mischievous cosplayer/gamer girl Konata Izumi, seemed to be practically every other straight male otaku's "waifu" at the time it came out (the 7th most Favorited female character on MyAnimeList as of the date of this article's publication).

Where There is Good, There is Also Evil, Even in the World of Anime Fandom.

Other anime series are decidedly more pessimistic about the otaku phenomenon, sometimes with good reason. Perfect Blue delves into the sort of crazy and possessive fans that idol singers unfortunately have to deal with. A lot of the folks at Gainax, otaku themselves, certainly soured on parts of otaku culture when director Hideaki Anno started getting death threats over the TV ending of Neon Genesis Evangelion.

The End of Evangelion movie was in part a harsh criticism of the worst elements of the anime fandom (freeze the frame during one of Shinji's meltdowns and you can see the death threat letters). Hayao Miyazaki himself is ruthless in his criticism of the otaku subculture, including what he sees as an increasingly insularity in the anime industry that's too willing to repeat old formulas and pander to the hardcore rather than look at broader inspirations. His casting of Anno, a notably self-critical otaku, as Jiro Horikoshi in The Wind Rises emphasizes reading the film as a cautionary tale about otaku impulses leading even well-meaning men astray, as Jiro Horikoshi's single-minded obsession with airplanes blinds him to the negative effects of his work.

The TV series Welcome to the NHK arguably goes lighter on otaku than some of its other targets of satire. Kaoru Yamazaki, while a major anime and eroge otaku, does go to school and have a social life, unlike the show's main character Tatsuhiro Satou, an aimless hikikomori (shut-in). The social problem of the hikikomori in Japan is frequently linked to otaku, however, and in the show's first episode Satou imagines a conspiracy in which broadcasting stations air late night anime with the express purpose of ruining people's lives and turning them into hikikomori. It's an anime series with a somewhat ironic (but in some cases useful) message:"Stop watching so much anime!"