Studio Ghibli Inc. is headed by two eminent directors: Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, whose distinctive styles cover a large spectrum of animated movies. Their cinematic sense and stunning depictions with unique watercolor finishes are perhaps unparalleled.

The range of styles in the Miyazaki catalog is extensive. Tonari no Totoro and Majo no Takkyuubin are movies which don fantasy elements in an otherwise largely regular and non-magical world. Whereas movies like Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi, Mononoke Hime, and Kurenai no Buta are created with high fantasy settings based on real historical backdrops, although almost every movie of his has, if not anything else, visual derivations from real places that he travels to before getting down to create. His major themes revolve around concern for environmentalism, pacifism, feminism, and a love of flying objects. His filmography does reveal some recurring visual and narrative idiosyncrasies. For example, characters in real world settings, such as Lisa in Gake no Ue no Ponyo and Tatsuo Kusakabe in Tonari no Totoro accept the existence of magical occurrences. There are elements such as humorous slow motion fights between characters, and funny pirates with ambivalent morality in Tenkuu no Shiro Laputa and Kurenai no Buta, and mechanics who sport large bushy mustaches or mad scientist hairdos in the above two movies and in Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi.

Isao Takahata’s movies like Hotaru no Haka and Omoide Poroporo have upheld neo-realistic cinema in the world of animation. He has mastered the art of meditative pacing and long silences inviting viewers to search for more meaning in the characters or reflect on the story. His natural flair with adaptations of other people's written works is peerless.

All ratings are accurate as of 12/02/2015.

Tenkuu no Shiro Laputa

MAL Rated 8.38, Ranked #168 | Aired Summer 1986

Tenkuu no Shiro Laputa is the first of Miyazaki’s work officially produced under the Studio Ghibli title and it brings most of his favorite themes at full throttle. Consider the massive moss-ridden gardener robot, who looks like he's merging with the earth below him every day, bringing a flower to Sheeta to mark the grave of a defunct robot in a meadow surrounded by a lush evergreen forest within the walls of a city named Laputa that floats in the sky. Just the abstraction of this imagery alone could be considered a representative summary of his art covering environmental concerns, love of flying, criticism of the war, and an empowered female protagonist.

Sheeta, an heir to the hidden island, Laputa, which is believed to be floating in the clouds, carries with her a crystal amulet passed on to her by her grandmother. Laputa was an immensely powerful nation that once ruled the entire world and holds treasures, magical power, and technology and being a descendant, Sheeta is sought after by a family of pirates called the Dola Gang as well as a government secret agent Muska who is aided by the army, in the hope that she will lead them onto this mysterious place. Upon escaping abduction, she is found by an orphaned kid named Pazu who belongs to the miner community and has a story of his own connected with the island. They find a kindred spirit in each other and jointly set out to discover their pasts.

Tenkuu no Shiro Laputa has a sublime introductory sequence. Sheeta falls from an airship in the sky which falls under the crossfire between the two abductors. The visually abstracted credit sequence is supported by the music of Joe Hisaishi and just when the crescendo of his composition hits a high, the unconscious Sheeta is shown falling and the crystal amulet lights up, making her float.

Sometimes Miyazaki's attempts at bringing all of his ideas to an orchestral crescendo get too convoluted for viewers to understand the bigger picture encapsulated by the plot, but in Tenkuu no Shiro Laputa it's still accessible. The two protagonists, one, a young boy who belongs to the community of coal miners in the underground, and the other, an estranged queen belonging to the ancient city of Laputa, that floats in the sky, unite in their ideas of peace and not exploiting the earth for greed or personal gain. There is a sense of universal truth, as Uncle Pom, a character who lives deep in the mines, says, "The earth speaks to all of us. If we listen we can understand."

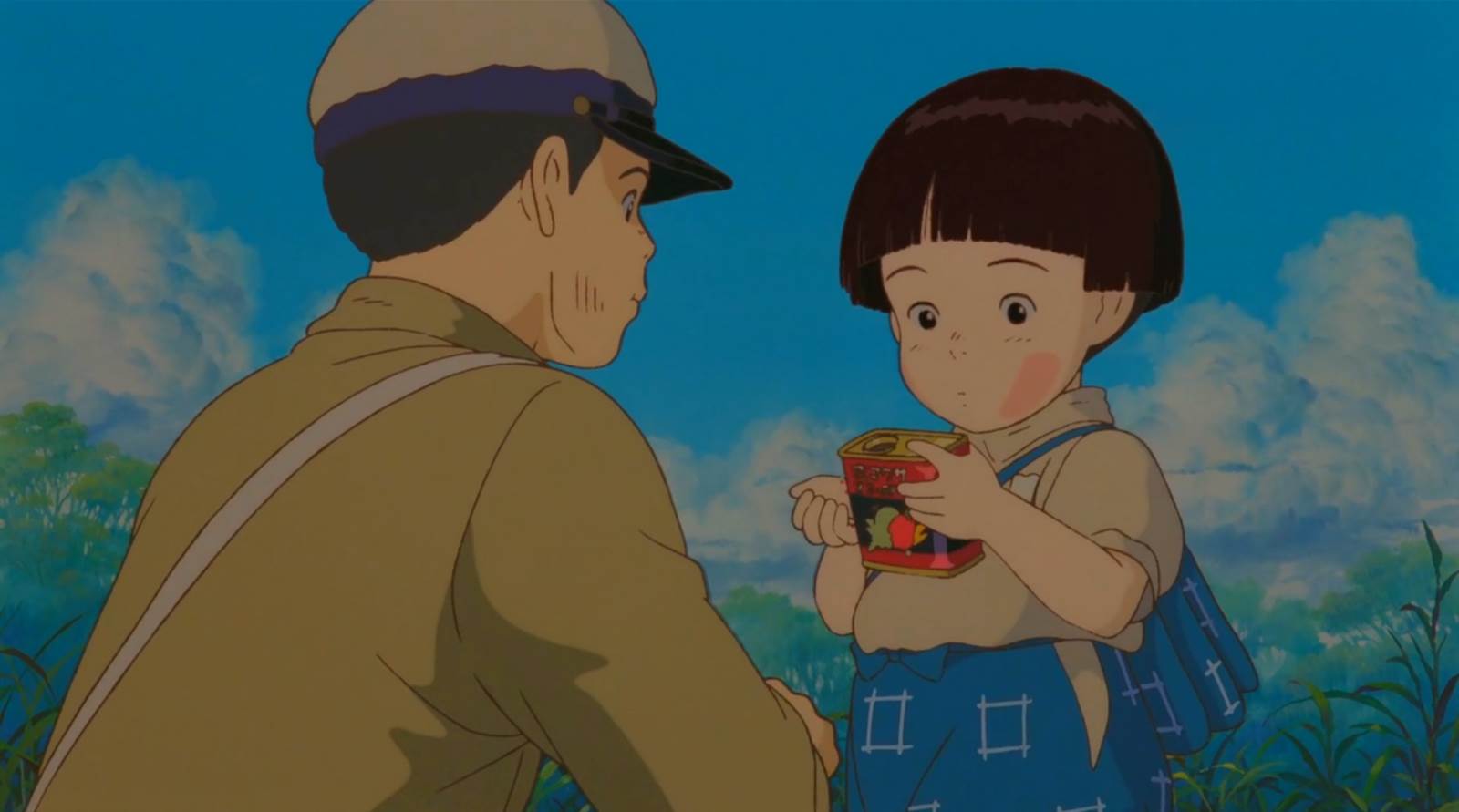

Hotaru no Haka

MAL Rated 8.60, Ranked #64 | Aired Spring 1988

There can only be a handful of live-action films, let alone animated ones, that can match the emotional intensity that Hotaru no Haka has to offer. It has drawn this reaction at nearly a universal scale, championing along with it the potential of animation as a medium for inciting true empathy in its viewers across the duration of a single movie. In fact, animation could have been the only medium to present the unsparing realism of the screenplay. For example, it’s hard to imagine a scene done with taste involving Seita, the young protagonist watching his mother's maggot-ridden dead body getting carried away, with real actors and video.

Isao Takahata has often said that this is not an anti-war film. It is a surprise that people would view it as just that. Seita’s aunt wouldn't have reacted any differently to her orphaned nephew and niece were it a series of imminent natural calamities instead of air raids. It feels like a film about adversity right from the beginning with war just a backdrop.

The persistence with which Seita turns unfavorable occurrences into a show of good cheer for his sister is a major gut-wrenching aspect of the film as we already know from the first scene that he dies a homeless man thinking of his sister, and the sense of impending misery creates an atmosphere of grief even when the characters are playing out their lives in a happy scene. He turns their finished box of sweets that also served as a metaphor for the countdown of their last good days into a sweet drink for his sister by adding water and shaking it and letting her do it herself. When she complains of itching and rashes he takes her to the beach on the pretext of a fun day out and gets her to wash those wounds with sea water (which, we later learn, didn't work very well, according to their village doctor). The memorable scene where Setsuko is afraid of the dark and Seita collects fireflies and lets them loose in their mosquito net not only solves the immediate problem but also triggers a memory of a Navy Review that his father was a part of, the events of which he then proceeds to narrate dramatically to her, only to turn around and find her asleep. The next morning she buries the dead fireflies and reveals to her brother that she knew of their mother’s death while he thought he had successfully hidden it from her. This breaks down young Seita’s strength and the manipulated joyful world that he creates for his sister at every step of their lives, and some part of him began living in that world himself.

She learns to lighten the burden on her brother and grows up with an unnatural quickness. These scenes are even tougher to sit through. Just before she dies of hunger she makes mud balls hallucinating that it is rice and even saves some for her brother. When Seita gets mauled by an owner for stealing potatoes and sugarcane, little rattled Setsuko offers to take him to a doctor. She even learns to save; when the last pieces of their fruit drops are unloaded on her hand from a can she thinks for a bit and then licks off the powdery tidbits that fell out and places the pieces back.

To call it a tearjerker bordering on melodrama or to question its audience manipulation might be valid when taken out of context. But it’s based out of a semi-autobiographical story written as an apology to the sister by the brother in question who actually survived to tell the tale and considering the events described there can’t be a shred of doubt about the desperation in it that Isao Takahata must have sensed. The plea of a reeling viewer of the movie would be that war should be avoided at all costs so as to not drive man to such extremities. But what of man’s heart, a war away from turning into stone?

Tonari no Totoro

MAL Rated 8.50, Ranked #102 | Aired Spring 1988

The beauty of Tonari no Totoro lies in the simplicity of the setting. Satsuki, her baby sister Mei, and their father, move into a village house by a forest. Their mother is recovering from a nameless illness in a hospital located few hours away from the house. The kids meet with some forest spirits near their new home, whom they share a friendship with, due to their inherent innocent nature.

As per standard Ghibli fare, the imagery is fascinating. The kids find in their house, black bug-like magical creatures called Susutawai, or dust fairies, which are believed to be illusions that one sees when a dark place is lit up. These creatures disperse and move out of the house when they sense that its occupants are good-natured. A dream sequence where Totoro and other spirits perform a ritual that makes acorns planted by kids grow into massive skyward trees is particularly beautiful. Totoro, transported by a flying top, first takes them to the treetops, and then on a trip across the village. When the girls wake up, they find that tiny plants have started appearing from they had sown the seeds.

With bare-bones setting at hand, Miyazaki injects much life and development into characters and the resulting interpersonal relationships are unlike many of his other movies. When these characters are sad, anxious, scared, playful, and excited the viewer feels the same and perhaps more than what the story might suggest. For example, before Mei gets separated from the village people, she nearly loses her way through the village while running blindly behind Satsuki. In this little sequence where Mei gets lost, the fact that the viewer gets slightly anxious, for such a trivial thing, holds testament to the movie's directorial sensibility. He depicts the sense of paranoia and loss of orientation that people face, when fearing for the safety of loved ones, by emphasizing how Satsuki forgets about Mei in her anxiety regarding their mother’s health. When Mei finds her way back Satsuki loses her cool on her starting a chain of events that lead to the extended search sequence. Pre-occupied characters such as the above often forget about each other, even the caring father of the girls is almost completely oblivious to their whereabouts while he's working, creating an atmosphere of unease when the girls go astray.

The dramatic quality of the movie is achieved without evil characters. The father calmly accepts and understands the kids' stories of unnatural events, and even takes them out to pay homage to the wood spirits.

The emotional expanse generated within a single sequence is one of the tools employed to prevent one single emotion from overpowering the viewing experience. A memorable scene is one where the girls wait in the rain alone for their father, carrying his umbrella for him that he'd forgotten to take to work. The bus that he's supposed to arrive back to the village in, stops in front of them, but he isn't there. Silent, multi-angled shots follow to create a tiny anxiety. Satsuki, a small frail girl who has assumed a motherly role to her little sister in the absence of their mother, carries Mei who's falling asleep. Mei, according her own father when he was carrying her earlier in the movie, was getting heavy. The two girls wait and anxiety moves onto sadness, but just then Totoro appears. Satsuki forgets her existing troubles and is stunned by the forest spirit that she has been dying to see for a while. She hands Totoro an umbrella and wakes Mei up. They look in wonder at this strange creature and the scene lightens up to humor. Then, a bus arrives in the distance, it first seems like their father's bus and the viewer is supplied with hope. But the bus turns out to be another weird magical creature, a galloping Carrolesque Cat-Bus that picks Totoro up and goes away. The scene has brought in a vibe of surrealist wonder. Next, another bus comes in, hope is restored, and the father walks out this time. This is cinema and Miyazaki is a master of it.

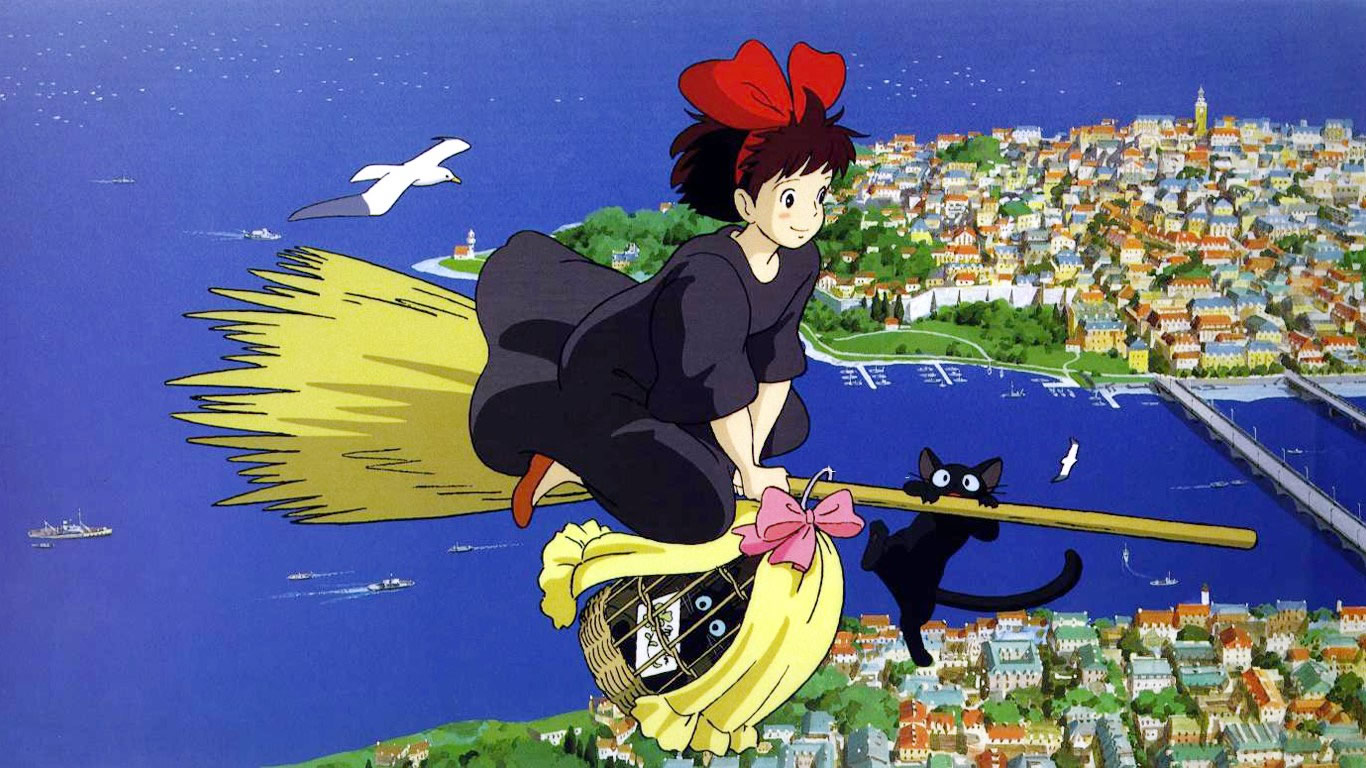

Majo no Takkyuubin

MAL Rated 8.26, Ranked #244 | Aired Summer 1989

The movie could be categorized as a classic ‘fish out of water' story but with a promising premise of a 13-year-old witch out in a big city to learn more about her craft and also find her ‘special skill'. Kiki leaves her home with a broom in hand and a cat for a best friend (in this world all witches have pet cats). She dislikes the standard black colored witch outfit for being ‘too dumb'. On her way across the sky, she meets another witch just like her who claims her special skill is fortune telling, especially of people's loves. We are struck with wonder at the possibilities of this world.

Although it's standard procedure for witches to leave home and be assigned to a city or a town, the people of Kiki's city are generally awestruck with the physical manifestation of a girl on a broom in the sky but only mildly surprised at the tradition of the witches, it seems to be a happening of a bygone era, and witches don't actually frequent these cities anymore.

Kiki’s sarcastic and wistful cat Jiji is the exact counterpoint that Miyazaki needed to make this enthusiastic and benign girl have meaningful scenes when she’s flying around (Some of the scenes in Porco Rosso felt like they needed a corresponding Jiji when the pig is all alone speaking to himself).

The sequence with Kiki's first delivery is handled with expertise. She decides to fly really high in order to get a bird's eye view of the city to find her delivery location. The delivery is a gift of a toy cat that looks just like Jiji. Although it's easy to imagine the problems that she might encounter, we don't anticipate she'll upset an entire forest of ravens and that Jiji might have to act like the non-living replica of himself that the two of them dropped in the forest during their tussle with the ravens. When we see that the kid's house has an enormous pet dog and that Jiji has to keep up with the act until Kiki finds the original in the forest, all the things we expect will happen do not. There is no steal and run fiasco at the end. In fact, they just leave with the lesson of not lying too high.

But Majo no Takkyuubin beats the stereotype of how these urban life stories unfold. Consider this: until the end of the movie Kiki's special skill is not revealed, although we think it's flying itself. Only because another odd situation is left unexplained- when Kiki and her friend Tombo's propeller bicycle nearly crash onto an oncoming vehicle on the road at full speed, something launches them just above it and saves their lives. When Tombo asks her if it's because she's a witch she says she doesn't know. We don't know either. The implied question is the whole point, and not the actual answer of it.

Omoide Poroporo

MAL Rated 7.65, Ranked #1101 | Aired Summer 1991

Isao Takahata's film about nostalgia and romance is known to have used calculated facial detailing to make the characters more realistic, and the film needs it, given that it features many closeups of conversations between people. As soon as Toshio steps in, the movie takes on a slightly different energy. He reacts and behaves in a much more lifelike manner than the standard animation fare.

I was reminded of Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man by James Joyce with the portrayal of Taeko's childhood development. She spends most of her early school days trying to understand the world around her in her own unique way. When faced with mathematical problems such as dividing a fraction by a fraction, she has trouble visualizing it. The sequence where she is assigned a single line role of ‘Village Child A' in a school play is exquisite. She takes up the job of enacting her one line with great purpose and even proceeds to change the words during a rehearsal, which the teacher promptly disallows. In the end, she actually manages to do what she wants to but in a manner that upsets no one.

An older but unmarried Taeko visits a family acquaintance in rural Japan, offering to participate in the safflower harvest to distance herself from city life, for a short span of time. Throughout her trip, she is wrapped up in childhood memories, which she shares with Toshio, spending her time reflecting on her present life.

The scene where young Taeko receives a slap from her father genuinely takes the viewer by surprise; in depicting life as it is, the moment when a slap is received is hard to anticipate, and its reasons are frequently obscure.

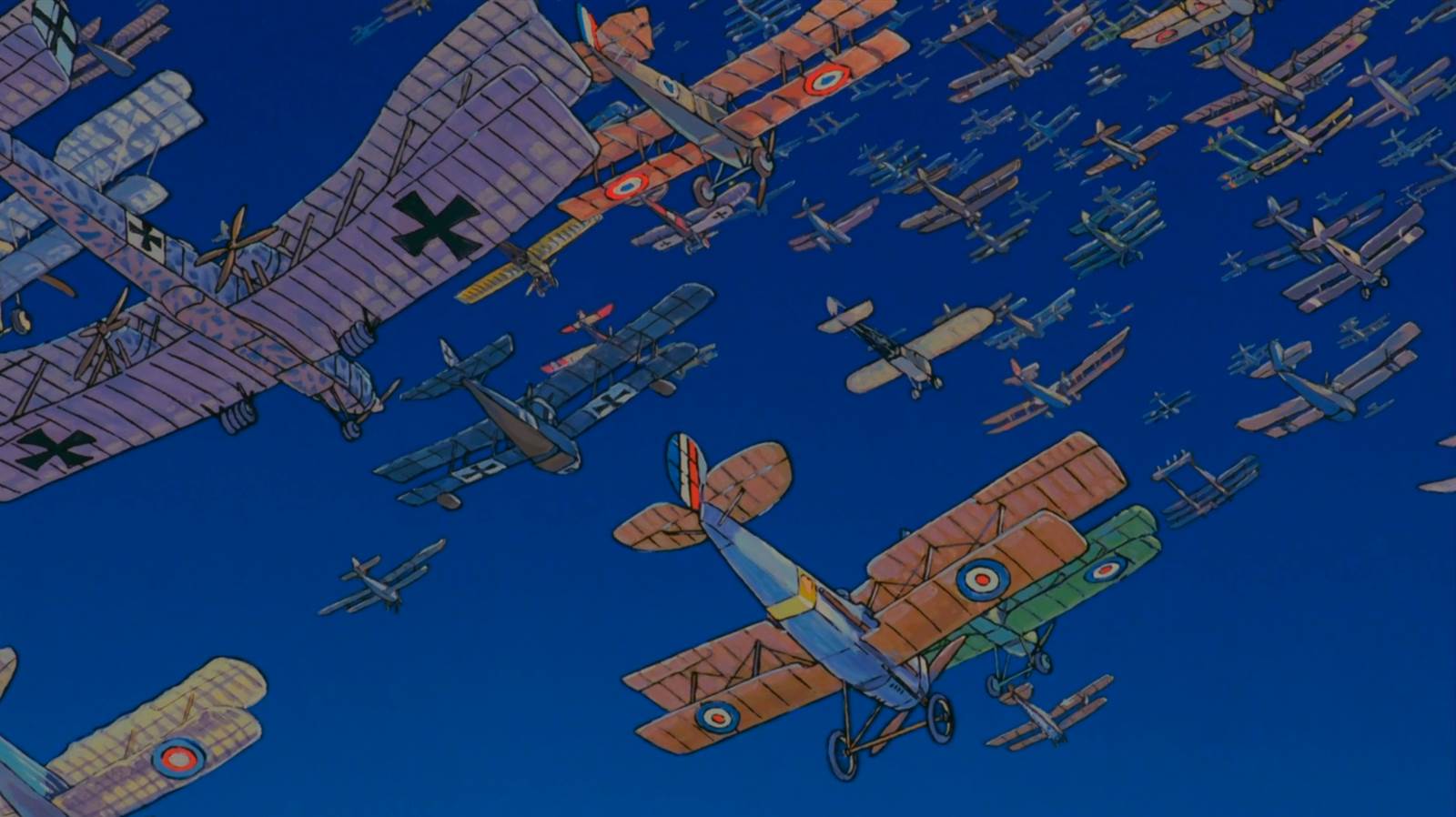

Kurenai no Buta

MAL Rated 8.03, Ranked #483 | Aired Summer 1992

"I'd rather be a pig than a fascist," claims Porco, the Italian ex-pilot who has been cursed to become a pig. There is an inherent pacifist sentiment attached to most of Miyazaki's movies which here lends itself as the political stance of the protagonist. Porco is revealed to be more multi-layered a character than it seems in the early sequences where he is the perfect anti-hero sipping wine and smoking alone by the beach on a beautiful island of a hideout in the Adriatic Sea; He tends to sport a self-destructive streak, often drawing comments from his friends and well-wishers to not be ‘pig-headed', and is valiant in keeping a high moral standard during battle, as he skips shooting an enemy plane down when he can't get a clean shot at it without hitting the pilot.

The sequence of dead fighter pilots floating and slowly rising to the sky implying their ascent to heaven while Porco, who is the lone survivor, watches them as they pass is especially poignant surreal imagery, and one of the very few serious scenes of the movie. There's a little breaking of the fourth wall when Ghibli's name appears on the parts of a renaissance plane that lies in the factory of Mr. Piccolo. The factory is also run entirely by women, since Piccolo's sons have moved on and Fio, who is the plane maker's granddaughter, is revealed to be a genius of an engineer by Porco. Miyazaki's feminism is also never too thinly veiled.

The movie also has a more grown up tone than the average Miyazaki offering- with slight sexual undertones and multiple references to Fio’s butt in various conversations, and the existential situation of the pig and his rival, the American Curtis.

Mononoke Hime

MAL Rated 8.81, Ranked #24 | Aired Summer 1997

The first time we see San, a wolf child, couldn't have been more precise in character definition. She sucks blood off of a wound on Moro, a god in the form of a wolf, to take out the bullet in her body; when Ashitaka calls out to her, she turns around and spits some blood, with her face smeared in it. In an instant you know she’s a fearless, and perhaps confused, warrior.

The story is set in a medieval world of gods and demons whose coexistence with humans has broken down. The protagonist, Ashitaka, is attacked by one such demon, which had taken over a giant boar, and upon killing it, takes upon himself a curse that will kill him. The dying boar remarks about how disgusting the humans are and the village doctor brings out the cause for his death, a piece of iron in his body.

After Ashitaka sets out to find out more about his curse he learns that his destination is a forest where “beasts are all giants, just like they were in the dawn of time.” He gets caught in crossfire between gods that are guarding the great forest spirit and humans who seek the forest’s iron sand. The humans are also after the forest spirit’s head, which the emperor of Japan seeks due to a belief that its possession lends immortality to the owner. Ashitaka tries his best to play the mediator between multiple rival groups when he senses that the antagonism between them will lead to disaster for all, and attempts to bring peace whenever he can.

Eboshi's village is a classic Miyazaki micro-world, where society is made up of outcasts who are given a redeeming chance at leading meaningful lives. Lepers make the rifles, and whores captured from brothels pump bellows in the factory while the rest of the men are at the front-line for war. But as Eboshi claims the women, have better aim and entrusts them to guard Irontown in her absence. In a sequence where Eboshi is knocked out by Ashitaka, the belligerent women are unable to fire their guns at him and the men are unable to block his way out to prevent him from escaping, making their individual ideals seem different from the ones Eboshi leads them to believe in. She manipulates them at many levels; during a face-off with the wolf girl she instructs two women, who have recently lost their husbands due to a confrontation with the wolves, to shoot San down. Yet just as one would expect from a Miyazaki story she is not an archetypal villain as she also genuinely cares for them.

It’s not just humans who are inscrutable and imbalanced in their actions- Okkoto, Moro, and the monkeys act blindly upon anger. It is the movie’s intention to depict hatred as a disjointing force; even allies against a common enemy end up spiting each other as peace can’t be achieved in an atmosphere of war.

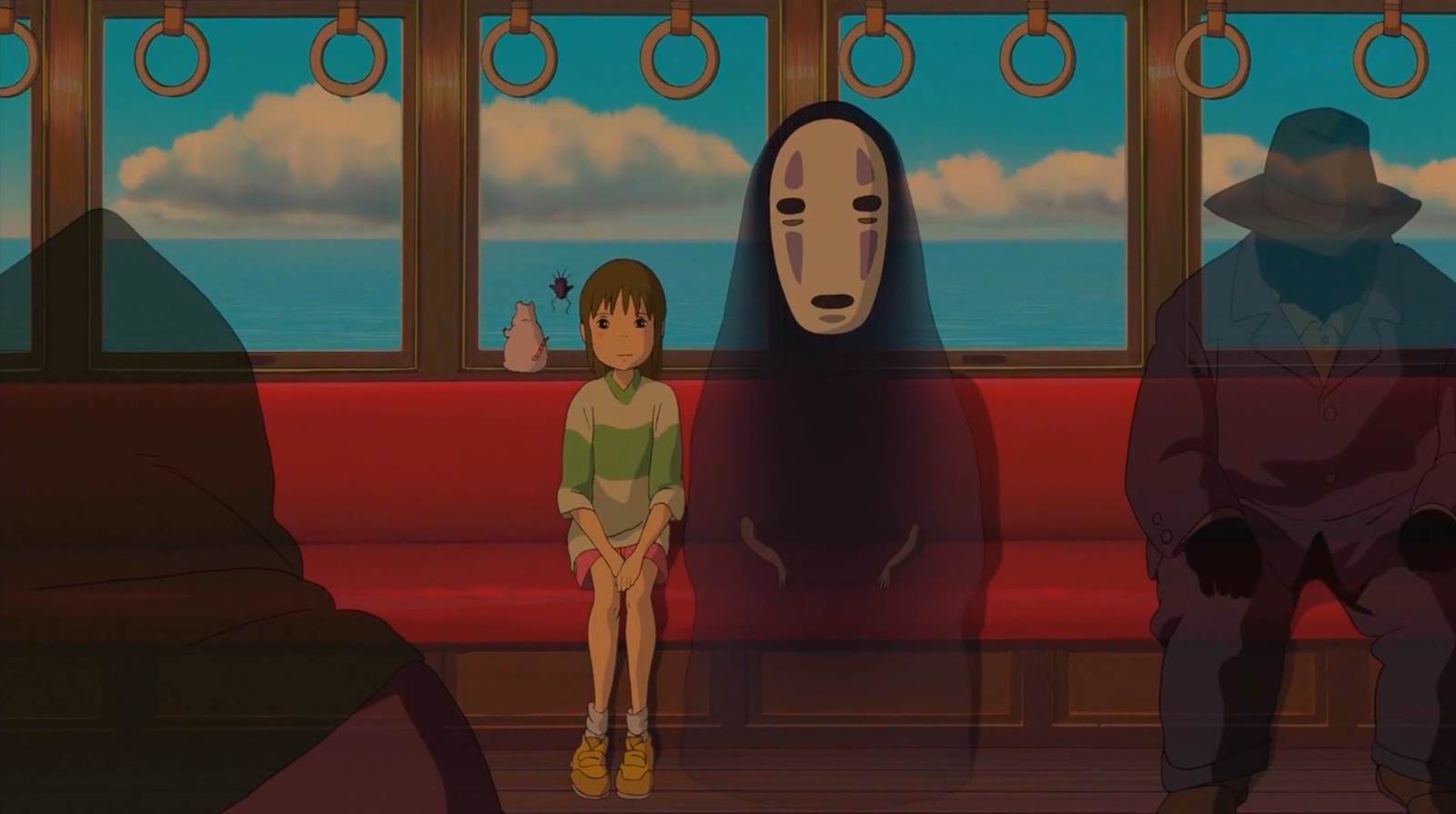

Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi

MAL Rated 8.93, Ranked #12 | Aired Summer 2001

Of all of Hayao Miyazaki’s high fantasy romps, such as Tenkuu no Shiro Laputa, Howl no Ugoku Shiro, and Mononoke Hime, Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi stands out as the most tightly knit written work and perhaps the one with the most courageous directorial effort. Apparently, he had made a movie specifically for ten-year-olds, who are neither small kids nor teenagers. Chihiro, the protagonist, falls in love towards the end of the movie, and it is not the teenage love that Kiki's craves in Majo no Takkyuubin, neither is it completely childlike like it is in Tonari no Totoro. It is an odd ten-year old’s love for an older guy who saves her from trouble.

The film has a nightmarish opening sequence. Chihiro and her parents are moving into a new town and they take an exploratory detour to visit the nearby sites, ending up in an abandoned theme park. Her dad smells some food nearby and the three of them follow it. The source of the smell of delicious food is from an empty restaurant with freshly made dishes displayed at the counters. Both starving parents decide to help themselves to the food and paying later when the shopkeeper back, much to the dismay of Chihiro who feels that they'll get into trouble. To this, the father replies "Don't worry, Daddy's here, he's got cash and credit cards." Chihiro decides to take a walk but soon she realizes they're in trouble when a mysterious boy tells her to get out of the place and she begins to see spirits and ghosts on the way. When she returns to the shop to warn her parents it's already too late. They have turned into pigs (consumerists), grunting and gorging on the food ravenously. It is now up to Chihiro to work her way through this spirit world and rescue her parents.

Considering that the plot involves a little girl who is the spirit world, in a bath-house for spirits, you might think that Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli would let their hair down with countless creative variations on the theme. And they do so, but around purposeful dialogue and a well-paced plot. The sheer visual absurdity of some of the characters makes for eye-candy elements, but their roles are also calculated. The many-limbed, insect-like boiler-room controller Kamaji, who has cast a spell on an army of soot sprites to continuously refuel the heating device, has two pivotal roles to play in Chihiro's journey. One is to help her get into the bath house, and the other to help her get out of it.

Haku, who initially seems to be a dragon spirit, helps Chihiro out in order for her to save her parents, who are bereft of their human memories and are herded with other pigs waiting to be butchered for the bathhouse’s dining services. She needs to get a job within the spirit bathhouse the residents of whom despise and look down upon humans. Chihiro gathers courage and slowly works her way through the place.

Miyazaki's environmentalism is placed cleverly; there is a massive stink-spirit who visits the bathhouse much to everyone's horror, and Yubaba orders Sen to deal with it. It turns out that it is a regular spirit who gets engulfed in human garbage, turning into a massive walking mountain of slush. One of the most interesting scenes in the movie is where a spirit called No-face, who assumes the personalities of the people around him, turns into an uncontrollable greedy spirit-eating monster in the company of the staff of the bathhouse. In Sen's company, it is timid and helpful. This spirit in the context of the story has no significant bearing but to reflect the viewer's the truth about the characters that they are looking at.

The sequence where Sen, No-face, and two spirits under a spell set out bravely to visit Yubaba’s twin sister, Zeniba, on a train that travels across the ocean is one of the most mesmerizing landscapes created by Miyazaki. It is especially well-timed considering that Sen has turned from a weakling to a courageous young girl who has even begun to inspire the people around her to disavow their greedy lifestyles and embrace their benign spirits. When they do reach their destination they are greeted by a one-legged hopping street lamp, who bows in welcome and leads them to the house they're looking for.

There is also a disturbing aspect of the movie in which Yubaba turns from a vicious, ruthless owner to an overprotective mother of an overgrown baby who she has never let out of its room. The love between them is proven plastic; neither recognizes duplicate versions of each other, namely Zeniba and three green walking heads, upon whom a spell is cast to look like the baby.

A lot of Studio Ghibli protagonists go out of their way to save their loved ones, turning wiser in the process, and Chihiro is no exception. Although, it has been viewed as having a murky undertone of trafficking that went on in the bath establishments during this period, the love with which the story is told stands tall in itself without indulging in deeper meanings.

Howl no Ugoku Shiro

MAL Rated 8.73, Ranked #35 | Aired Fall 2004

Howl no Ugoku Shiro opens with some of the most promising introductory scenes in the Ghibli collection; Sophie, who works as a hatter, encounters a powerful young wizard named Howl. He saves her from two men who were harassing her on the street, by sending them away marching with a casual swish of his hand. Then, upon being followed by black slug-like creatures, Howl levitates, taking her with him, and teaches her to walk on air, bringing her safely to her destination. Soon Sophie falls under a spell cast by one of Howl's romantic pursuers, "The Witch of the Waste", turning her into an old woman, and preventing her from revealing the nature of her curse to anyone. She decides to travel to a wasteland in order to find a way out of it, rescuing a hopping scarecrow with a turnip's head which was stuck in the bushes on the way. Unable to find shelter there, she latches onto Howl's moving castle and begins living in it with a taking fire demon, Howl, and his apprentice.

Howl’s powers are sought out at war, which has taken place as the neighboring country’s prince is believed to have gone missing in Sophie’s country. By the time Sophie gets to know the wizard, his suave ways make way for deep-rooted angst laden with inner disharmony, especially when she learns that he turns into an enormous, terrifying bird when at war, a transformation that grows in him every day making it increasingly difficult for him to return to human form.

Gake no Ue no Ponyo

MAL Rated 7.95, Ranked #586 | Aired Summer 2008

‘Ponyo' is the name that the five-year-old Sosuke gives to a magical goldfish that he's rescued and brought back home. The goldfish wants to become a human, and with her bestowed powers and a drop of human blood that she tasted off of a cut on Sosuke's hand while getting rescued, she is able to do so temporarily. She manages to find Sosuke, although her wave spirit sisters who carry her along with a frenzied enthusiasm to land cause a tsunami in the process.

The movie has common elements with Tonari no Totoro: family emergencies, fear for loved ones, two estranged children out against the world (or the elements in this case) but Gake no Ue no Ponyo is woven with such fairy tale fabric that it is almost an ode to all the children who watch Studio Ghibli films. The channel through which Miyazaki's high fantasy unfolds is usually based on air and flying, but Gake no Ue no Ponyo is about the ocean, and he manages to bring about the same bursts of imaginative space with ease. Fujimoto's anthropomorphic wave spirits flush and dart with the power to usurp anything in their way. Sailors look at a mountain in the horizon but quickly realize it is actually the sea that has risen in response to the moon that has moved out of its orbit. The scene where Ponyo nears the cliff where Sosuke stays and nearly gets trapped by a fishing trawler and in the process gets her head stuck into a glass bottle is truly claustrophobic, especially in contrast with the preceding scenes of underwater wonder and magic.

As with many of his films, the villain, or the obstacle in the path of the hero, is empathized with. Being an over-possessive and worrisome father, he supplies both obstacles and humor to the storyline. The scene where he addresses Ponyo with the name he had given her and she screams out in protest -"No I'm Ponyo"- is wonderfully comical, considering that Miyazaki thoughtfully has made the onomatopoeic name sound like something that a five-year-old would name a squishy and cute object and the viewer doesn't expect this cuddly fish to have been named after the mythological warrior, Brunhilde, by her father.

Childhood and parenting are the other major Miyazaki themes. "If only you could remain innocent and pure forever,” says Fujimoto to his sleeping daughter. Whereas Lisa, upon seeing the odd-looking Fujimoto before starting her car calls him a ‘freakshow' as an afterthought but quickly corrects herself in her son's presence and tells him "Don't you call people freakshows, we never judge others by their looks." And that is justified; she is a high-strung mother living alone by a cliff with her son and the weight of the world on her shoulders.

Kaguya-hime no Monogatari

MAL Rated 8.42, Ranked #140 | Aired Fall 2013

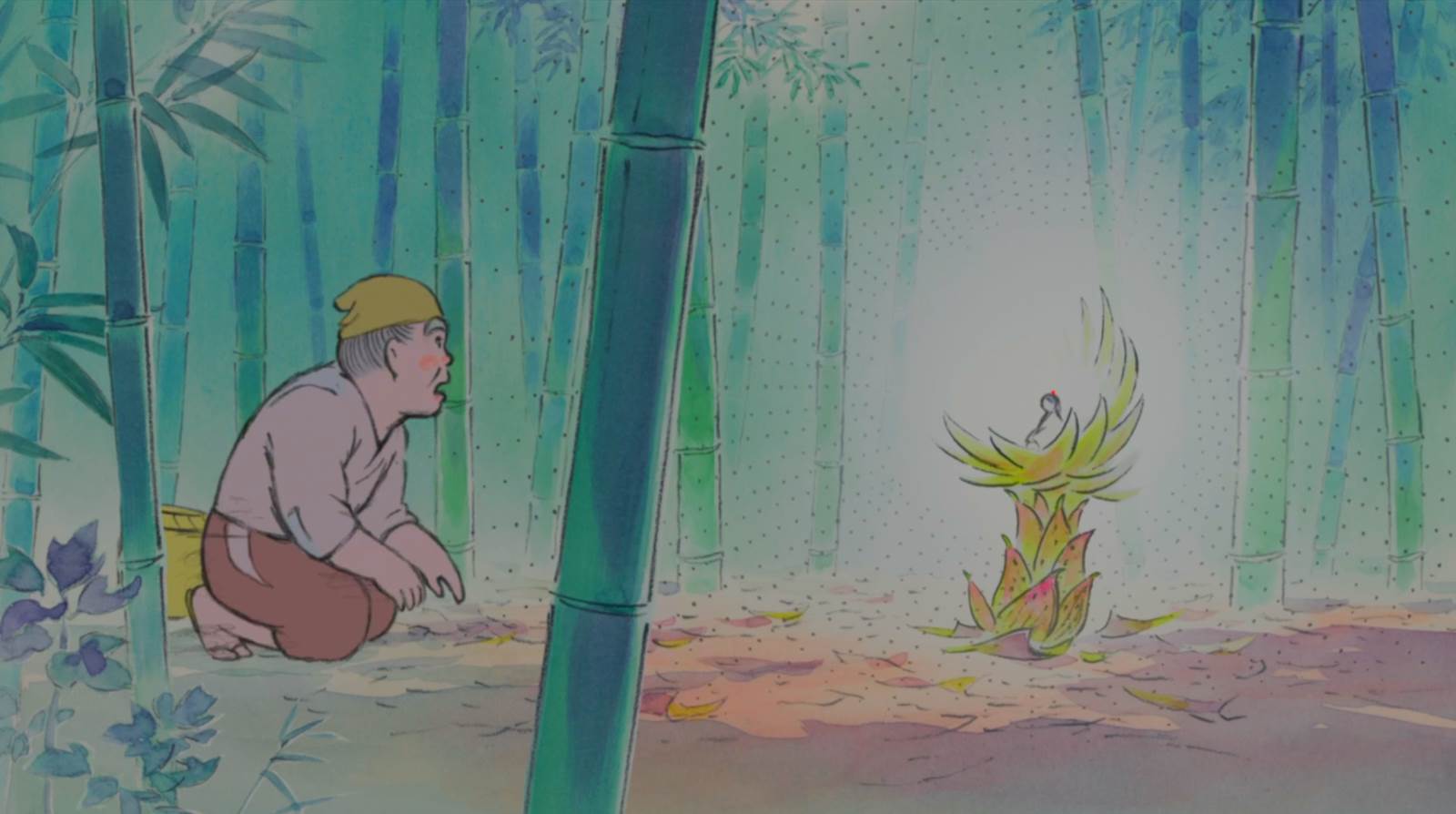

Kaguya-hime no Monogatari is Isao Takahata’s masterful adaptation of a Japanese folktale about a girl who is found within a bamboo shoot.

The angelic baby girl is found by a bamboo cutter, who takes her home to his wife. When the wife suddenly bears milk in the baby’s presence the couple begin believing that they have been assigned a divine task to bring her up. Soon, the bamboo shoots start supplying gold and exquisite robes to the woodcutter, who interprets these occurrences as a sign that the 'Princess' must be taken to the city and brought up in a noble manner. He then sets up an entire system for her upbringing: a large mansion, a governess who will teach her the ways of the high-born including removing eyebrows (Hikimayu) and dyeing teeth black (Ohaguro), and servants who will watch over her every need.

‘Princess' grows up to be an enthusiastic young woman who is also prone to intense bouts of despair. We are made aware of the happiness with which she accepts impermanence as well as her suffering when she relives fond childhood memories. As a toddler, she is consumed with the joy of playing with other children who call her ‘little bamboo'. In one of the defining scenes of the movie, she is seen singing a folk tune with her friends who are taken by surprise at her knowledge of the words to the song. Suddenly she walks away from them and takes off with another song that nobody's heard. Her friends stop singing and look on in awe and puzzlement. At the end of her song, she has tears welled up in her eyes and when her friends ask she tells them she doesn't know why. They joke that "she's weird" and within moments she bursts into laughter.

She promises one of her closest friends Sutemaru that "his little bamboo will always be with him, forever and ever" and as soon as she comes back, gets taken to the city by the bamboo cutter, much to her dismay. We assume that she'll be grieved looking at the new surroundings, but instead she is overjoyed. Her father, the bamboo cutter, who possesses a certain child-like pettiness and obsessiveness, takes to the idea of championing his daughter's nobility and turns completely deluded by it. Although her beauty invites suitors from the highest order of nobility but, much to the father's horror, she rejects every one of them, sometimes with wit, sometimes with luck, and one time with the help of her mother. She knows that she doesn't belong to this world and plainly states that she would kill herself in an event of forcible marriage.

A major portion of the movie's success should be credited to Joe Hisaishi’s soundtrack, which captures the subtlety of the conveyed emotions with precision. The story is told with the backdrop of 'mono no aware’ that makes the protagonist feel ill at ease with the present due to the passage of time. But we ourselves are consumed with sadness by the passage of her story.