Adaptin’ ain’t easy. That may be the most obvious sentence I’ve ever written, but it’s something we tend to forget when watching a favorite book or comic reimagined through TV or film. It isn’t just a matter of taking the original and adding motion, voices, and music; every element of the source material—from story arcs to character development to general tone and themes—has to be taken into account and converted to its new medium’s time restraints, structural limits, and narrative conventions.

So when I say the Baccano! anime is a stellar adaptation, I’m not saying it’s an exact replica or “better” than Ryohgo Narita’s original light novels. What I am saying is that it’s a prime example of how an anime can be faithful to the spirit of its source material while gleefully rearranging its pieces, preserving the original’s voice even as it adds its own to the chorus. When it comes to a great adaptation, sometimes what you change is just as important as what you keep.

General discussion of the Baccano! anime TV series and the first novel (1930: The Rolling Bootlegs) below. It helps if you’re familiar with the anime, but I’ll avoid any major spoilers.

Every medium has its own strengths and weaknesses that help immerse the audience in a story. Novels don’t (usually) have musical scores or frame-by-frame illustrations, but they can draw you into their worlds through vivid descriptions, lyrical prose, and especially by giving you an up-close-and-personal look into another person’s thoughts and feelings.

The Baccano! light novels (LNs) accomplish much of this through a combination of colorful, distinct dialogue as well as Narita’s narrative voice. He has a simple but evocative style, equal parts wry humor and empathetic warmth, that makes it easy to sink into the story and engage with even the most minor of individuals via our mostly omniscient, mostly third-person narrator.

I say “mostly” because the The Rolling Bootlegs uses a first-person framing device, where the central story is being told to a modern-day Japanese tourist in NYC. There are also a few (surprisingly poignant) passages told from the first-person perspective of a minor character later on. However the bulk of the novel is a fantastical gangster tale set in Depression-Era New York. It's written from a third-person POV that bounces between multiple characters, providing insight into their histories and thoughts. (Although, again, he's only mostly omniscient. When it comes to the eccentric thieves Isaac and Miria, even our godlike narrator can only toss up his hands and shrug at times.)

The constant shift between characters—often as one person encounters the other, “transferring” the narrator from Firo to Ennis and so on—not only creates the sense that there is no single protagonist (one of Narita’s stated goals), but also forwards the novel’s own ideas about how “coincidence” and “destiny” are two sides of the same coin. Each character’s actions—and especially the emotional impact they have on each other—coalesce to form a bigger picture. Parts become a whole; individuals form relationships; meaning arises out of chaos.

While the Baccano anime technically could have replicated Narita’s breezy prose or inner monologues, it would’ve drastically slowed the story, bogging it down in lengthy voiceovers. Baccano is many things, but it is most definitely not slow. It’s a stolen town car careening down an alley; a runaway train barreling towards Grand Central Station.

Screenwriter Takagi Noboru could keep Narita’s dialogue, and in many cases did (for example, Isaac and Miria’s repartee is frequently ripped straight from the novels). But to preserve the fast-paced nature of the LNs, the anime had to sacrifice the narrator’s voice and the level of intimacy with the characters and replace them with elements that would work better in a visual medium, still immersing the audience while also maintaining the original’s lively spirit.

The anime succeeded for a mess of reasons, such as the streamlined stories, trimmed-down cast of characters (yes, there are even more characters in the LNs!), expressive animation, engrossing vocal performances, a jazzy score, and frenetic action sequences. That said, I want to focus specifically on the two boldest changes, and the ones that really allowed the anime to not only stay faithful to the original’s tone but in many ways enhance it: Framing devices and narrative structure.

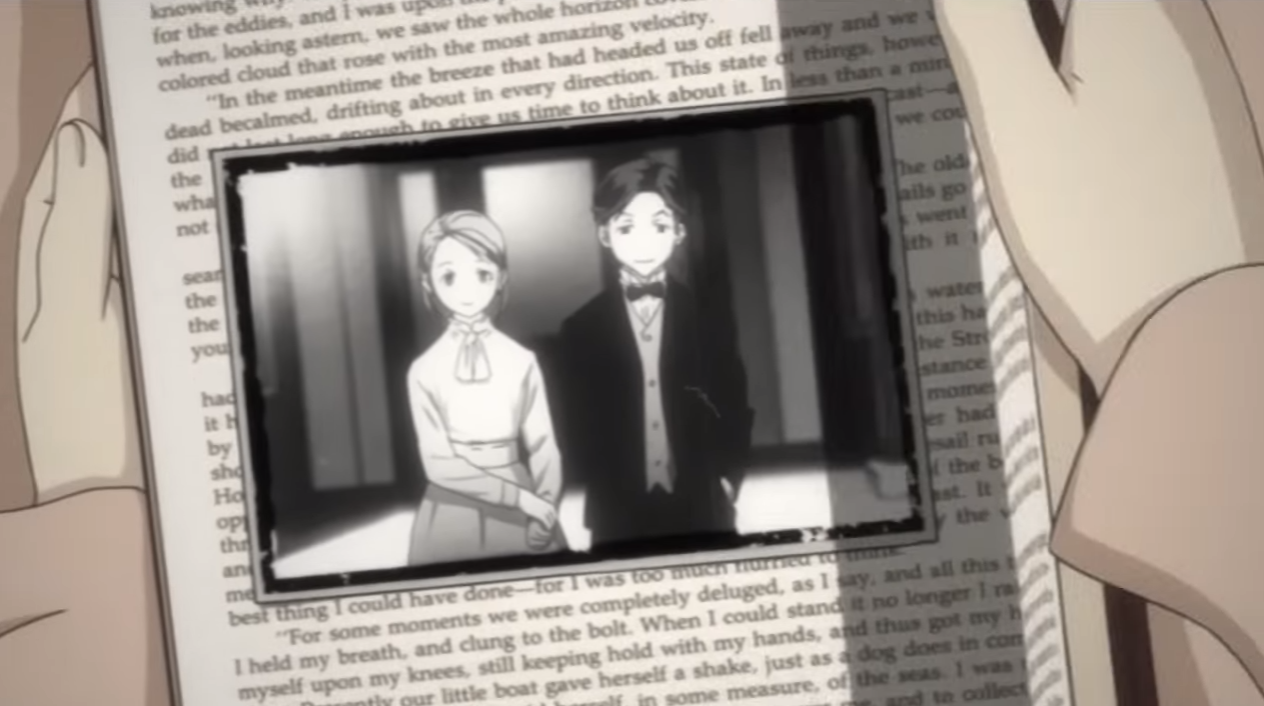

The modern-day Japanese tourist in the LN gets replaced in the anime by two 1930s American journalists. They’re following a series of strange occurrences revolving around people who are rumored to be immortal, and are trying to form these seemingly disconnected pieces into a coherent whole. They even have a whole conversation in the first episode about where to begin and who the “main character” is, echoing Narita’s own desire to write a story without a true protagonist.

The journalists succinctly capture Narita’s overarching themes about how humanity creates meaning out of chaos, but they’re also a unique way for the anime to pull the audience into its story. The anime can’t immerse us as deeply in the characters’ thoughts as the LN did, so it immerses us in the characters’ world instead.

We’re not outsiders being told a decades-old history. We’re members of the population, trying to piece together events as they occurred. The anime dives straight into Baccano's outlandish universe of immortals and gangsters and alchemists, and it never once comes up for air. (As an aside, Funimation’s phenomenal dub takes this immersion one step further, its big city dialects and speakeasy slang all but soaking the audience in 1930s pulpy gangster goodness, making it one of, if not the, best English dubs ever produced.)

This framing device also helps the anime set up its narrative structure, a fragmented tale that jumps between times, locations, and characters with maniacal glee. While the original novels do insert some flashbacks and the series as a whole jumps through time quite a bit, each book is mostly linear, following the events of a single location and year in more-or-less chronological order.

The anime series, meanwhile, throws the first four Baccano LNs in a blender and hits “puree.” The audience ends up traveling simultaneously down three timelines, to say nothing of an extended 1700s flashback thrown in for good measure. It’s daunting at first, but if you’re willing to ride through the initial confusion, the pieces do start clicking together. Once they do, you find yourself rolling along with the story and characters, solving concurrent mysteries as the events of early years fit with the later years, answering some questions and raising others.

It shouldn’t work, but it does. And in the process, the Baccano! anime finds a way to not only preserve but actually amplify Narita’s original narrative structure, taking his multiple perspectives and slightly shifting timelines and making them louder, more disorienting—and, in the end, more cohesive, too.

In the original novels, there are events in Volume 1 that don’t get resolved until Volume 4. In the interim, we drift away from those characters. But in the anime, we see those tales happen simultaneously. We learn of a character’s fate at the same time his sister does. We figure out who’s immortal and who’s not in one year at the same time we’re seeing them gain that immortality in another. We become the journalists, piecing stories together, creating a coherent whole out of erratic fragments, just like our original LN narrator does.

By understanding both the spirit of the source material and the strengths (and limitations) of their own visual medium, the anime team turns four rollicking novels into a frenetic, compulsively bingeable anime series that still resonates with viewers (and remains one of my all-time favorite series) almost a decade after its release.

Baccano is Italian for “ruckus” and can be used to refer to a big, noisy party. Narita captures that sense of rowdy joy through his snappy prose and perspective shifts; the anime recaptures it through its narrative structure and vibrant music and visuals. The light novel’s story could only be told in prose; the anime’s could only be told in animation. And yet through it all both tell the same tale: Of uncertain heroes, bombastic villains, and eccentric guests of honor, as they dance through the party, bumping into one another, sharing snatches of speech that slowly form a conversation. Coincidences so myriad, they just might be destiny.