A Heated Subject of Debate

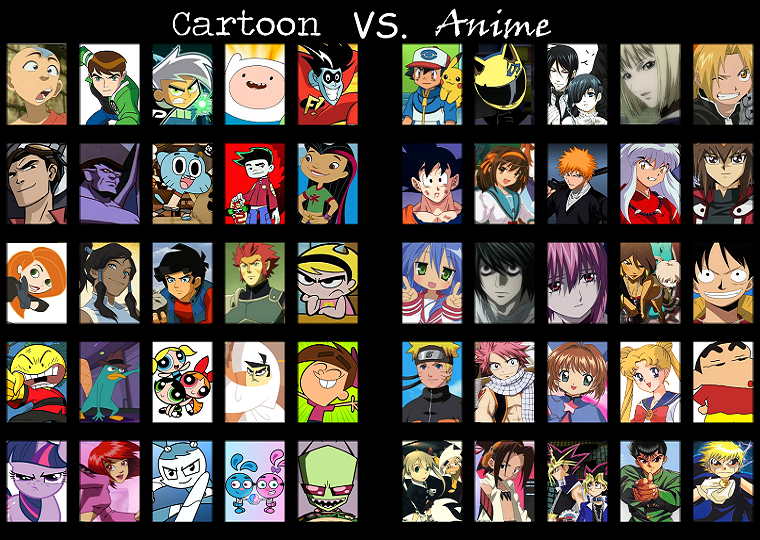

American cartoons vs. anime. People get really opinionated on this topic. On one hand, there's those who throw a fit if you dare call any anime a "cartoon" because "cartoons are for kids." On the other hand, "anime is teh s uck". No one would deny there's pretty big differences between the Japanese and American animation industries, but is one truly greater than the other? And as anime increases in influence in the West, are they starting to share more in common?

Quality

Let this be clear: American cartoons don't all suck. Neither does all anime (though you probably knew that if you're on an anime website). Sturgeon's Law (that "ninety percent of everything is crap") holds equally true on both sides of the Pacific. Having a general preference for one country's animation over the other is understandable as a matter of personal taste, but you can't paint all of a country's animation with one brush. To dismiss The Iron Giant and Rick and Morty as "American trash" while claiming Garzey's Wing is somehow elevated above a "mere cartoon" by virtue of its national origin is absurd. Dismissing Grave of the Fireflies and Fullmetal Alchemist as "junk for kids" while singing nostalgic praises for He-Man is equally idiotic.

Genres

Image Source: Fantasia

Image Source: Fantasia

While the quality of cartoons from America and Japan may not see a significant difference as a whole, there are distinct trends in the popular styles and genres of American cartoons versus anime. American cartoons trend towards comedy, and while they haven't always been aimed at kids, the majority of American animation is family-friendly. Anime has its comedies and its kids/family shows, but the range of genres and demographics is much wider, including realistic dramas that are almost never considered for animation in America.

The differences between the two animation industries can be explained historically. The first American cartoons were theatrical short subjects. When you went to the movies in the 1930s, you'd be paying for a full experience, with newsreels and shorts - both animated and live action - preceding the feature (there was also often a cheaper "B movie" following the main attraction). In that context, animated shorts were most effective as little bursts of comedy. They also served as ways to showcase studios' music libraries - a precursor to the music video - establishing a connection between the cartoon and the musical that doesn't really exist in Japan (but oddly enough, there are lots of stage musicals based on anime - yet hardly any actual anime musicals).

For a long time, feature-length animated films were almost in the exclusive domain of Walt Disney. Disney had experimental ambitions early on in his career, but following the commercial failure of the artier and more adult-oriented Fantasia he retreated to the safety of the fairy tale formula that made him so much money on Snow White. This started the stigma of animation being primarily for kids and families, a stigma which became all the more severe when animation moved to television in the '60s. TV killed the theatrical short subject, and with it, the subversive comedy of the Warner Bros cartoons and the visual experimentation of UPA's shorts. While those theatrical shorts were shown before adult-oriented films and as such often aimed at the adults in the audiences, on television, most animation got relegated to Saturday mornings when most adults were sleeping in. The Flintstones had some success as a primetime sitcom, but as other primetime cartoons flopped, it would be over two decades before The Simpsons made comedy cartoons for adults commercially viable again in the mainstream.

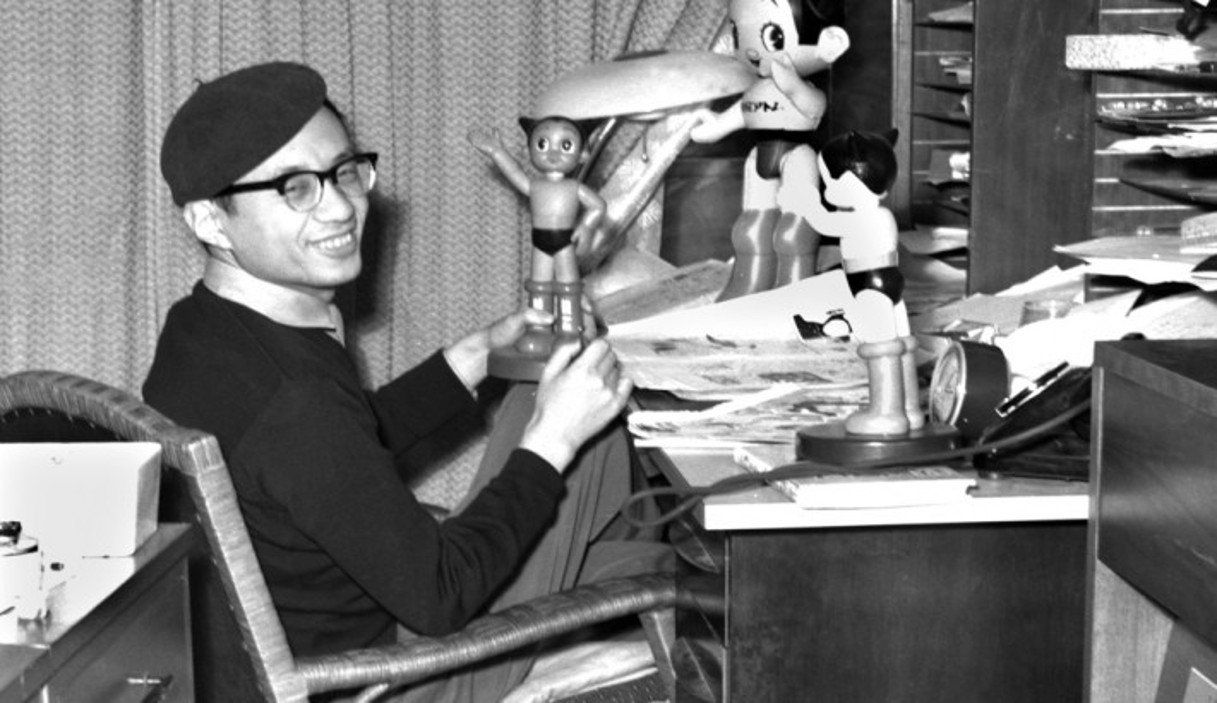

The differences between anime and American cartoons in terms of genre diversity can be traced to the differences between their most influential figures; Disney and Osamu Tezuka. Tezuka admired Disney, borrowing heavily from his art style, and sure enough, many of Tezuka's biggest successes, works like Astro Boy and Kimba, were kid-friendly works heavily indebted to Pinocchio and Bambi. But where Walt grew artistically conservative with age, Tezuka's experimental streak never went away. In addition to his childrens' series, he also did medical dramas, historical works, philosophical meditations, gruesome horror, and even erotica.

It's important to note much of Tezuka's manga couldn't have been published in America at the time. The Comics Code Authority, established in 1954, was extremely restrictive (even moreso than the Hayes Code that dictated Hollywood censorship in the same era) and killed off the once popular horror and romance comic genres in America, leaving only squeaky-clean superheroes and kids stuff surviving. American comics would recover eventually, but without such harsh restrictions, manga from the '50s through the '70s grew to encompass every genre and every audience.

Since the anime industry was so tied to manga, it was only a matter of time before anime reached towards these wider demographics. The first anime TV series in the '60s were mostly kids' adventure shows, but by the '70s shows aimed at teens such as Mobile Suit Gundam were dealing with darker subject matter, and more adult-oriented series like Lupin III began to show up. By the '80s the first generation of anime otaku had come of age and anime for adults became a regular thing. Economic restraints also helped diversify anime. If an American TV network made, say, Rose of Versailles, it would almost certainly be a live action show. But at Japanese networks, where money is tighter and animation comes cheap, it's not so bizarre or unexpected for a more realistic drama to go the anime route.

Visuals

Image Source: Bakuman

Image Source: Bakuman

Most people who watch animation can generally see a few seconds of a show and determine based on the animation itself whether it came from America or Japan. Yet defining a particular "anime style" is difficult, despite what those old "how to draw anime/manga" books might have you believe. You can't pull up a picture from Ghost in the Shell and a picture from Lucky Star and really say they share a "style." So how is it so many people can "know it when they see it" and identify what looks like "anime"? Well, there are common visual trends in anime (the big eyes and tiny noses, sweatdrops and other SD stylizations), but what makes anime generally look so different from American animation might be less about any particular art style and more about a difference in priorities and animation techniques.

Image Source: Clutch Cargo

Image Source: Clutch Cargo

American theatrical animation in the '30s and '40s was all "fully animated", with new drawings either every frame ("on ones") or every other frame ("on twos"). This process was both too painstaking and too expensive to carry over in the transition to TV, so "limited animation" techniques were born, such as animating on lower frame-rates and limiting movement by only redrawing specific body parts rather than the full character. The artistry took a serious hit in the early years of American TV animation, and most American cartoons from the '60s through the '80s look like crap because of it (Clutch Cargo, pictured above, is a notorious example). American TV cartoons today still use limited animation techniques but generally look better than older ones due to a combination of factors (higher budgets, more appropriately streamlined designs, more direct involvement of the storyboard artists in the final product, digital software easing workflow).

Image Source: Neon Genesis Evangelion

Image Source: Neon Genesis Evangelion

To paraphrase Bane from The Dark Knight Rises, American cartoons only adopted limited animation, while anime as we know it was born in it, molded by it. Early TV anime had animation even more limited than American TV cartoons, but the animators figured out ways to use the style to its advantage without detracting too much from the cinematic qualities of the visuals. Cinematic qualities were in fact emphasized. Where the best American animators have a tendency to compare their craft to acting, Japanese animators tend towards a focus more on cinematography. That's not to say that there's no impressive shot compositions in American cartoons or that there's no expressive character animation in anime, but the different priorities explain a lot about the differences in visual styles. Anime tends to dismiss the idea of a consistent frame rate entirely; one shot can be just a moving camera over a still image while the next can fluid and action-packed. Even today in big budget anime movies, you're likely to find scenes animated "on threes" or "on fours" next to scenes "on ones" or "on twos" (while big budget 2D animated movies in America do switch between animation "on ones" and "on twos" depending on the complexity of the scene, the difference in fluidity is almost imperceptible and far less dramatic than the bigger frame-rate changes in anime). At this point this is no longer an imposed limitation, but a conscious choice.

Other differences are based in production schedules. Anime generally focuses less on lip-sync than American animation both because it's an easy place to cut animation costs and because anime production schedules tend to start animation production before recording voices; in America, voices are typically recorded first (Katsuhiro Otomo went the voices-first route for Akira, which is why the mouth animations are so much more detailed there than in other anime and why it's so weird watching the movie dubbed).

Convergence

Image Source: Batman: The Animated Series

Image Source: Batman: The Animated Series

While anime started off heavily influenced by Disney and other American cartoons before evolving into its own thing, in recent years American cartoons have been increasingly influenced by anime. In the '90s the influence was rarer and subtler. Bruce Timm cited Akira as one of many influences and John Lassetter of Pixar has long sung the praises of Hayao Miyazaki, but nobody would ever describe Batman: The Animated Series or Toy Story as looking like anime (though there is one particular anime that looks a lot like Batman: The Animated Series: The Big O, which was made by Sunrise animators who'd previously worked on the DC superhero cartoons and picked up notable design influences).

Image Source: Avatar: The Last Airbender

Image Source: Avatar: The Last Airbender

After the Pokemon boom in the early 2000s, a lot of American cartoons started looking like anime. The best of these anime-esque cartoons were made by people who truly understood the influences they were working from: Glenn Murakami's well-animated 2003 Teen Titans series, George Krstic and Jody Schaeffer's short-lived but hilarious mecha parody MEGAS XLR, the early seasons of Aaron McGruder's The Boondocks, and of course Bryan Konietzko and Mike DiMartino's Avatar: The Last Airbender, one of the best-written animated serials ever and probably the American show that the most people have mistaken for anime. The worst were cheap cash-ins on a trend that didn't really know what they were doing (is anyone actually nostalgic for Kappa Mikey or Loonatics Unleashed?).

Image Source: Steven Universe

Image Source: Steven Universe

Now American animation finds itself in an exciting place: the rise of the first generation of American animators to grow up with anime as a regular part of their media diet. The rise of more complex serialized storytelling in cartoons such as Adventure Time and Gravity Falls might have more to do with general trends in American TV post-Sopranos than any specific anime-related influence, but it's allowed a move towards a style of storytelling that's been long associated with anime.

The influence of anime has produced some great cartoons. Bee and Puppycat combines the magical girl action of Sailor Moon with the low-key comedic sensibility of King of the Hill. Steven Universe is filled with references to everything from Utena to Evangelion, and its combination of quirky humor, smart world-building, and heavy emotions makes it one of the best cartoons from any country. Yoh Yoshinari's a big enough fan that he drew Connie from Steven Universe - as well as Dipper and Mabel from Gravity Falls - into Little Witch Academia 2 (it should come as no surprise to anyone who's seen Panty and Stocking that the guys at Trigger are huge fans of American cartoons).

Avatar: The Last Airbender begot The Legend of Korra, which was less consistent story-wise but a major step up visually. Now much of the Avatar/Korra crew is working on the Netflix reboot of Voltron. Most of this anime influence is still regulated to children's programming; adult cartoons in America still lean heavily towards the comedic, aside from the occasional arthouse films like Anomalisa. But even if America doesn't ever regularly produce adult animated dramas on par with Millenium Actress, the future of American animation is looking bright in large part thanks to the influence of anime.