Spotlight: A History of Shoujo Manga

When we think of shoujo manga, we usually think of pretty character designs, high school settings, sparkling comic panels, cliché misunderstandings, and honey sweet moments. Great titles such as Full Moon wo Sagashite, Kareshi Kanojo no Jijou, and Skip Beat dominate the contemporary face of shoujo manga. These stories of adolescent love, friendship, and handsome men are extremely alluring to young female readers, but shoujo manga as a particular subset has a long and interesting history much departed from its modern conception. This article will attempt to highlight some of the key elements in the history and development of the modern shoujo manga, briefly featuring notable works that marked its inception as well as the socio-political aspects that influenced its rise in popularity.

As early as 2009, there were forty shoujo manga magazines circulating throughout Japan, compared to only twenty seven shounen manga magazines. Each of these shoujo magazines had specific targeted age groups and specialized genres and subgenres. Historical romances, shounen ai, science fiction, slice of life, school dramas, and fantasy. Shoujo manga magazines offered a wide selection of different fantasies and adventures for young girls that varied drastically from genres to art style.

However, this diversity was, at one point, in peril. The publishing environment before the Second World War saw an abundance of publishers, including modern big names like Kodansha and Shueisha, with copious magazine publications. For instance, Shueisha, known now for its famous magazine Shonen Jump, established six magazines, targeting both boys and girls, in its first year of operation. By the end of World War II, paper and material shortages had all but choked the life out of manga publishers. Only one girls’ magazine, Kodansha’s Shoujo Club, remained at the end of the war.

However, manga magazines endured. They provided a brief and much needed respite from the harsh realities of the post-war era. Children’s manga was extremely popular for precisely this reason. By the time of Japan’s surrender in the summer of 1945, many children who had been born during the wartime era could only remember being at war. Daily air raids, harsh provisions, and escaping to bomb shelters were normal experiences, and the summer of 1945 introduced to children for the first time what they had never known: peace. In many senses, the children of Japan did not know how to live a normal life that was not involved in the toils and service of the now removed wartime emperor. The reintroduction of children’s magazines thus boomed in the post-war era and gave the perfect conduit to capture a number of things: the slice of life experience, exciting new adventures and romances, and a secret lament for the shame and loss during the war.

In addition, the same conditions that killed many publishers and forced massive consolidation in the industry were the same reasons magazines rebounded rapidly at the end of the war. Relative to other things, magazines were still easy to produce with minimal labor and material costs. First issues of post-war manga magazines could be done even when only one color of ink was available and could utilize recycled paper. The infamous akahon, or “red books” named after the color of their covers, dominated the early post-war era. With so little income across Japan, these cheap manga books were priced at anything from ten to ninety yen, easily affordable for young kids. Osamu Tezuka, the known father of the modern manga, was known to have drawn a number of manga in these akahon.

Osamu Tezuka's Ribbon no Kishi

Osamu Tezuka's Ribbon no Kishi

As wealth flowed into the pockets of ordinary Japanese families, the akahon lost relevancy by the end of the 1950s, replaced by other manga forms crucial to the development of the medium. By then, however, Tezuka had already serialized what many consider the starting point of the modern shoujo manga. Ribbon no Kishi (Princess Knight) was a serialized work between 1953 and 1958 and would become the starting point for long running serialized story manga, stories that could run from just a few magazines to ten years, telling the story of a princess who must pretend to be a male prince to inherit her rightful throne. This motif of a girl dressing up as a boy is certainly one that finds its way into more modern shoujo manga such as Shoujo Kakumei Utena (Revolutionary Girl Utena). While Tezuka’s story certainly lays some of the fundamental thematic groundwork with cross-dressing, romance, drama, and fantasy, Ribbon no Kishi more importantly represents a turning point in the conception of the story manga.

Manga targeted at girls is by no means a new phenomenon. One can sift through the archives and find silly manga in the early 1920s clearly meant for girls to enjoy. However, the notion of a story manga dedicated to girls started thirty or so years after the first panels targeting a young female demographic were printed. The story manga was a departure from the narrative style of the past, where manga predominantly featured more episodic content dedicated to comedy. With the introduction of story manga, manga could enter the realm of novels and film and be expressive, romantic, historical, and more. This helped to legitimize the industry as one producing works beyond mere comedy and pulp fiction.

During the 1960s, most of the mangaka publishing in the major shoujo publications such as Shoujo Friends and Shoujo Club were men. This included big name mangaka in the industry such Tetsuya Chiba, famous for his magnificent sports manga, Ashita no Joe, who published works such as Akane-Chan, Mama no Violin, and Yuki no Taiyou in shoujo magazines. The father of horror manga, Kazuo Umezu, published a number of his horror works in Shoujo Friends. Shoutarou Ishinomori, known for Kamen Rider, also published a short story collection in Shoujo Club.

However, it is the 1970s that should likely be considered the Golden Age of shoujo manga. The 70s gave rise to the Year 24 Group, the shoujo manga equivalent of the Bloomsbury Group. The name derives from the fact that many in the group were born in the 24th year of the Showa period (1949). While some consider Tezuka to be the producer of the earliest renditions of the modern shoujo manga, the Year 24 Group masterfully recreated the genre in their image. It is the aesthetics of this period as well as its focus on gender and sexuality that would be the standard for all great shoujo manga.

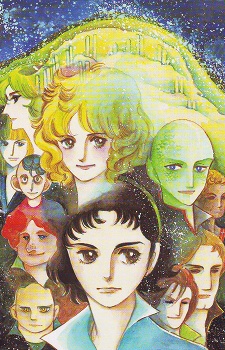

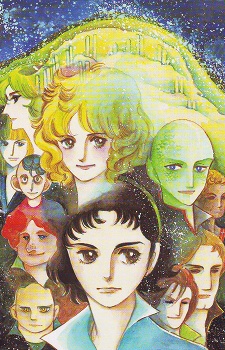

Moto Hagio's They Were Eleven

Moto Hagio's They Were Eleven

It is an era of Moto Hagio, often considered the mother of the modern shoujo manga, who wrote a number of science fiction classics, including Juichinin Iru! (They Were Eleven), historical manga such as her epic Poe no Ichizoku (The Poe Family), and a number of early shounen-ai works such as Thomas no Shinzo (The Heart of Thomas) that would be representative of the shoujo genre. Unlike Tezuka’s Ribbon no Kishi, the flowing hair of the main character in Juichinin Iru! and the panache of Poe no Ichizoku, along with its beautiful men, are much more visually in line with what we see in shoujo manga today.

Riyoko Ikeda's Rose of Versailles

Riyoko Ikeda's Rose of Versailles

It is also an era of Riyoko Ikeda, most known for her masterpiece Berusaiaya no Bara (The Rose of Versailles). Published in Margaret Comics, Riyoko’s manga depicted the themes so popular in shoujo manga even thirty years later, including historical elements from the 18th and 19th century, an aesthetic that is focused on the details in the eyes and long flowing hair, as well as internal questions of gender identity and sexuality, as is referenced by the main character’s upbringing and masculine name, Lady Oscar.

There are many more, from the shounen ai manga of Yasuko Aoike to the historically focused works of Toshie Kihara, but they all had one thing in common. This era of manga artists all contributed to establishing the broad themes and aesthetic cues that make shoujo manga what they are. While we may originally trace the modern shoujo manga’s lineage back to Osamu Tezuka, it is inconceivable that his Ribbon no Kishi and the works of the Year 24 Group are comparable in terms of their inevitable influence.

Furthermore, it is notable, in the development of shoujo manga at least, that feminist criticism had begun in Japan in the late 1960s and early 70s. Still under the sphere of American influence, which was experiencing its second wave of the feminist movement, the feminist movement in Japan was, broadly, about women’s liberation. This included ideas such as liberating women from an oppressive household system and redefining ideas of husbands, children, households, and love.

This took shape in shoujo manga as well, as more liberated female characters in the shoujo works of Moto Hagio and Riyoko Ikeda and others represented a shift towards more female agency. In addition, the presence of shounen-ai manga by Yasuko Aoike and Keiko Takemiya, who published perhaps the first shounen-ai manga “In the Sunroom”, were interpreted as not just a new intriguing fantasy for young girls, but also brought forth questions and topics of liberal gender and sexuality that had previously not been considered. Male characters often shared effeminate features in shounen-ai, yaoi, and boys love manga. Many have often attributed the popularity of these sorts of characters to the fact that these characters may represent the alter egos, or hidden desires, of the female reader to escape some of the trappings of the female sex.

From left to right, Revolutionary Girl Utena, Cardcaptor Sakura, Sailor Moon

From left to right, Revolutionary Girl Utena, Cardcaptor Sakura, Sailor Moon

This sort of criticism and feminist perspective would dominate the 80s and 90s, as the Year 24 group continued their careers. To supplement this, a new trend of fighting heroines from manga such as Shoujo Kakumei Utena, Bishoujo Senshi Sailor Moon and Cardcaptor Sakura also chimed in the latter half of the 1990s. Utena, Sailor Moon and Cardcaptor Sakura brought forth ideas of transformation, whereby young girls turned into something that enabled freedom, power, and agency. Utena, specifically, set herself apart from the pack as she was not only a fighting heroine, but a heroine wearing male clothes, which represented a callback to manga such as Ribbon no Kishi and Berusaiaya no Bara. It is thus no coincidence that Utena deals heavily in topics of sexuality and gender identity.

Other manga, such as Fruits Basket, where characters turned into their zodiac animal when hugging members of the opposite sex, utilized this theme and transformation in different ways, but an underlying motif of puberty, growth, and sexuality still existed. As Fruits Basket continued into the mid-2000s, we were given numerous titled from Nana to Skip Beat, which have since flourished with critical acclaim, that dealt with the transformative nature of the lives of young girls as they moved from one stage of their lives to the next. One may notice that at this point, the trends in shoujo manga have become to dissipate and grow vaguer, and the types of stories within shoujo manga have become vast and innumerable.

Indeed, shoujo manga has grown enormously since the second half of the 20th century, and it has become difficult to paint broad strokes for shoujo manga in the 21st century that bears significant truths worthy of analysis. Nevertheless, the history of shoujo manga remains as it was, rich in historical context and deep in its evolution from its early comedic stages. While shoujo manga is nowadays criticized for its overemphasis on school environments, underwhelming teenage romance, and childish teen dramas, there still exists the intrinsic desires, dreams, and aspirations of young girls. These dreams can be fleeting and ephemeral, but shoujo manga preserves them in their entirety, now, and forever. |