Dense, dark, corrupt, chaotic – these are all adjectives which could be used to describe Neo-Tokyo, the postmodern, dystopian setting of Katsuhiro Otomo's cyberpunk masterpiece Akira. Otomo personally adapted his manga series into the well-known feature-length anime of the same name, and the film served as an introduction for largely uninitiated Western audiences to the world of Japanese animation. What is it about the Neo-Tokyo cityscape which remains so fresh, so distinctive, nearly 30 years after the film's release?

The History of Neo-Tokyo

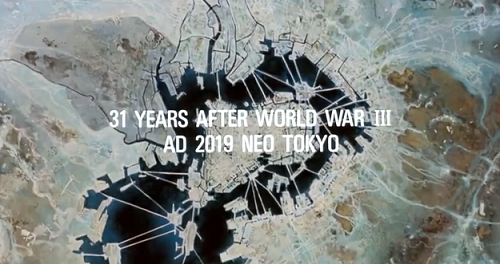

We don't know too much about the detailed history of the city – it's briefly explained that a massive explosion, presumed by most to be a nuclear bomb (though actually caused by the series' titular character), destroyed the city of Tokyo in 1982, kicking off an international incident and igniting World War III. The story then picks up 37 years later in Neo-Tokyo, an artificial island built in the middle of Tokyo Bay and connected to the mainland by a series of bridges and highways. The ruins of the old city lie mostly abandoned along the city's outskirts, though with Neo-Tokyo scheduled to host the 2020 Olympic Games (spooky, isn't it?), necessary construction projects including the Tokyo Olympic Stadium have meant the beginning of the mainland's redevelopment.

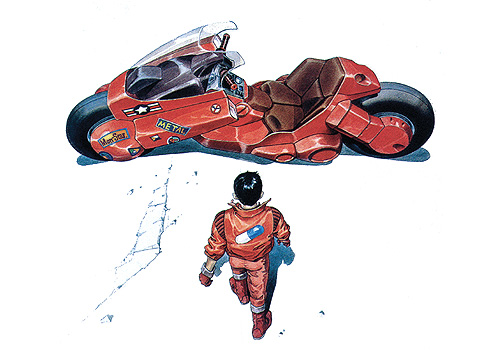

The Look of Neo-Tokyo

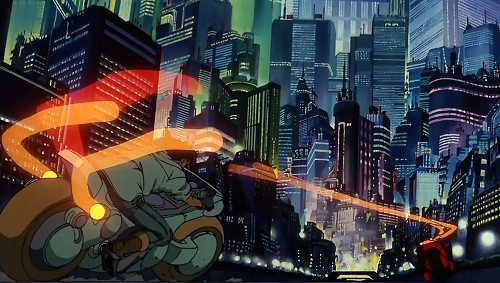

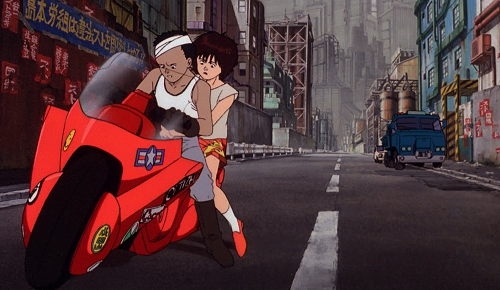

The Neo-Tokyo skyline is choked with skyscrapers – a seemingly endless wall of concrete, glass and steel as far as anyone cares to see. Even with numerous different levels and terraces for vehicle and pedestrian traffic jutting every which way, the city is still hopelessly crowded and claustrophobic. The noise and light pollution is constant. Bridges connect the island to the mainland like threads tenuously lashed together into a net to stop the city from sinking under its own weight. Neo-Tokyo is a city which has vastly outgrown its carrying capacity.

The Feel of Neo-Tokyo

In many ways, Akira epitomizes the cyberpunk genre – the city of Neo-Tokyo is highly mechanized, impersonal, managed by a corrupt, authoritarian government and populated by cynical people for whom life is cheap and nothing really matters. Otomo really outdid himself in crafting the feel and general aesthetic of a world which is at once nightmarish, but at the same strangely appealing and totally believable, if not inevitable. Though we see plenty of it in the film, the nihilistic mood of the city really comes to life in the manga, in which the expansive cast of characters and subplots give us a more complete look at just how little everyone in this world really seems to care about the idea of living.