Chihayafuru

Available on Manga Store

New

Sep 27, 2016 6:39 AM

#1

| I had to study about poems because of school so I thought this manga will be a good subject for that. But since there's no thread for poems in this forum, I thought I should make one and post about my own interpretation of the poems. You may as well post yours. Suetusugu once said that readers should pay attention to the poems because there is story for them and when it comes to poems in this manga and I think the most important poem in this manga series are the poems for the main characters name that Suetusugu picked for them. Chihayaburu - as we all know, Chihayaburu is about a passionate and unchanging love. Which the characters in this manga has shown us, with their passion and undying love for karuta. Even though they may get nothing in the end, they still keep on playing, that's how much they love karuta. So this is the English translation for Chihayaburu: "Even when the gods Held sway in the ancient days, I have never heard That water gleamed with autumn red As it does in Tatta's stream" I think this poem really suit Chihaya. Because that poem is talking about how, out of all those passionate gods, there is someone in which passion surpasses them all. In this manga, we have seen how almost every players love karuta. They worked really hard for it, they have passion for it, they love it and their love for it never change. But out of all those passionate players... there is Chihaya whom everyone named as "karuta baka" They are all passionate when it comes to karuta, they all love karuta. But Chihaya's passion and love for karuta is on completely different level than all of them. Everyone who sees how much she loves it can't help but feel touched by her passion for karuta. There was even a line like this about her " I have never seen anyone as greedy as her. But I also have never seen anyone who loves karuta as much as she does" - This line is the closest translation of Chihayaburu poem. Out of all those passionate gods who live for thousands of years, they have never seen someone who's as passionate as that person/god that the poem is referring to and in this manga, out of all those passionate karuta players. Chihaya's passion is something that surpasses them all. Tachi Wakare - for Taichi Mashima. "Though we are parted, If on Mount Inaba's peak I should hear the sound Of the pine trees growing there, I'll come back again to you." Most people see that poem as someone saying that he will be coming back. Similar to that line" Just call my name and I'll be there", which is actually right. But this poem is not just about coming back but mostly about waiting. It's a poem about love that is willing to wait no matter how long. A love that will never change. If you will pay attention. You will notice that, the person in this poem is in a love with no assurance. He is not sure about what she really feel for him or whether there is someone else that she like. He left without ever finding out about her real feelings. That's why he said "if I hear you pine for me" - if she feel the same way about him, then he doesn't need to say "if I hear you pine for me" because she will surely pine for him. But since he is not sure about what she really feel for him, all he could do is left her a promise. A promise that no matter what happen, no matter how long it takes, he will always be waiting for that day that she will pine for him. While he's on Inaba mountain. A lot of things can happen. She may fall for someone else and forget about him. There was never assurance that she will pine for him. But despite knowing that she may never ever pine for him. He's still willing to wait for that day and so no matter where he is, no matter how long, if he hear her pining for him, he will return right away. That's how much he loves her, he is willing to spend his whole life waiting for something that may never happen. He's that confident that his love for her will never change no matter how many years has passed. Which really fit Taichi's character. Especially if you think about how the author gave such a big emphasis about his love for Chihaya. A love that he's been carrying ever since they were kids. A love that didn't change even after years of being a part. A love that didn't change despite seeing all of her flaws. A love that have no assurance of being returned someday. But despite not being sure on where his love will take him. He stayed with her through thick and thin. No matter how painful it is, he bear with it for years while hoping that someday his feelings will be returned. Arata - There are two cards that was associated with Arata. One is poem 76 and the other one is poem 11 (which Suetsugu drew him holding) Poem 76 "Over the wide sea As I sail and look around, It appears to me That the white waves, far away, Are the ever shining sky." Poem 11 "Over the wide sea Towards its many distant isles My ship sets sail. Will the fishing boats thronged here Proclaim my journey to the world?" Poem 76 It's about someone who left the place that he love. That the whole time he's traveling, his eyes was only set in the direction of that place. So he never paid attention to what's around him. But when he finally decided to look around, he realized that what's around him and what's waiting for him is a much much better place. This really suit Arata because the whole time. We have seen Arata as someone who wasn't able to move on from that old apartment and his memories from when he was in Tokyo. He let himself get stuck in that room and so he never realized the changes around him. He never realized that he Chihaya and Taichi already moved on from that apartment memory. He never realized that he was the only one inside that room . But the moment he started to think of making a team is also the same moment where he started to think of what's around him. Just like the traveler in that poem, he started to look at what's around him and there he saw that what's waiting for him is a much better place. Arata's development is still far from over, he just started to pay attention to what's around him. There's still more to come for him, because we still don't know the answer to the question from Poem 11. "My ship sets sail Will the fishing boats thronged here Proclaim my journey to the world?" Arata started his journey toward his goal but the ending is still unknown, it's still unsure whether he will succeed or not, so we have to wait to find out the answer to that question. |

CuebeeSep 27, 2016 8:38 AM

| *Yawn* Not gonna argue again with a stupid troll. |

Mar 11, 2017 9:45 PM

#2

| Bumping this thread to the top of the list, even if it turns out to have been just for a little while. I've felt bad about letting this topic just sit there without response while the thread slowly dropped down the page - despite all the effort you put into it. With my first reply I'll say that I'm not really qualified to comment, though the topic fascinates me. In spite of my lack of qualifications I feel I must also first observe that the original language appears to have gone missing, a little, in the way you wrote this all up. Personally, I think including Romaji transliterations will be useful and I'll probably add that -some time soon - if no one else does it first, for the poems you highlight. I'm also writing to ask that you include the source(s) of the translations you posted. I think it is useful to note that modern Japanese people also require translation from the original language in which the poems were written. Teika himself interpreted older sources when he collected them into the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu collection - a collection for which in turn there are various English translations as well. For the bi-lingual edition of the manga series itself, for example, Yoko Toyozaki and Stuart Varnam Atkin were credited with the respective translations. An edition which fortunately incorporates romaji transliteration. Stuart Varnam Atkin's translations have been retained for the newly released English e-book edition of the first volume, but not all romaji survived in the margins. His is a different approach to the English translations you relied on for your analyses. Arata's poems can be used to demonstrate the reasons why I think romaji matters, or why learning the pronunciation of kana characters can be of benefit. There is information in the way the poems sound when recited, and this can be a benefit to understanding the series beyond the karuta matches. That the white waves, far away, Are the ever shining sky. "The White Waves" in this translator's choice for what can also be written as "Shiranami". Which happens to be in the name of Fuchu's Shiranami Karuta Club. [Name as given in the first volume in the bi-lingual edition.] To the selected three of the OP, I'm adding a fourth person, Wakamiya Shinobu, and a few preliminary lines from one of the poems associated with her, arguably of equal importance. As is the case with Arata, there is more than one possible poetic association in the collection, based on the sounds in her name. Her arrival, I think, is foreshadowed with that poem's playing card in the first chapter. Shinofuru koto no Yowari mo so suru "Second verse" of poem 89, quoted above from the bi-lingual edition from which I've also taken Stuart Varnam Atkin's translation: So why not now, before our secrets Spill from my feeble heart? Another poem has been explicitly attached to a particular volume (34) and the latest chapter to date, the 178th song, has a book open, to suggest we read beyond the pages contained. Will the series become a completely open book, when we understand the thoughts behind these lines or their placement within the story? Probably not, but I agree with you that the poems need a thread of their own here. Hope we haven't let you slip through our fingers... Edit to expand on information revealed in chapter 178 but which might be easier found in a thread with this title by someone with an interest in such topics. This really does require commentary well beyond what I'm capable of providing, and I think, well beyond what any translator of this 178th chapter will likely include in the translation of the chapter itself. Perhaps it is useful to note that Ian Hideo Levy's book,「英語でよむ万葉集」"Eigo de yomu Manʾyōshū", "Reading Manʾyōshū in English", is depicted and referenced in that chapter. It is a small volume with a selection of poetry preserved in the Manʾyōshū anthology. Levy opens with: "Tell me your name"; followed by "Many are the Mountains of Yamato"; before getting into the "White, pure white" chapter, p.29ff, we see reflected in Chihaya's conversation. That section itself begins with lines from "Two poems on the crescent moon" and Levy next provides his English translation for and commentary on, the "Tago no Ura" poem, p.34ff *. A poem itself written as an envoy for a longer poem on mount Fuji specifically as well. Suo's commentary appears, to me, to come almost directly from the pages following the "spread", pp34/35, on which the book is seen open in "our" latest chapter to date. Levy identified the poem as the transliteration and translation of Book 3, Poem 318 from Manʾyōshū. University of Virginia (UVa) eText: http://jti.lib.virginia.edu/japanese/manyoshu/Man3Yos.html#318 The poem was also included, as the fourth poem, in Ogura Hyakunin Isshu, by Teika - but in a slightly different form and language. A good opportunity to mention "Pictures of the Heart" by Joshua Mostow. Mostow who commented on the different versions of that poem and who deferred to Levy for the English translation we saw in the 178th chapter of Chihayafuru, although Mostow referenced Levy's book "The Ten Thousand Leaves" as his source. (... Prof. Mostow, who has yet to comment on Chihayafuru.) |

removed-userMay 5, 2017 10:10 PM

Mar 16, 2017 7:58 AM

#3

| Thanks for the reply, I completely forgot about this thread. I hope more people will talk more about the poems too. |

| *Yawn* Not gonna argue again with a stupid troll. |

Mar 17, 2017 6:16 AM

#4

| Just wanted to talk about the poem from chapter 179 that took my interest. "The rooster's crowing In the middle of the night Deceived the hearers; But at Osaka's gateway The guards are never fooled." As for my understanding, this poem contains a lot of bitterness, but I could be wrong so I looked for other opinions about this poem. One of them is from http://essaychief.com/research-essay-topic.php?essay=2364453&title=Analysis-Of-hateful-Things-By-Lady-Sei-Shonagon "The rooster's crowing In the middle of the night Deceived the hearers; But at Osaka's gateway The guards are never fooled. Hateful Hate"ful, a. 1. Manifesting hate or hatred; malignant; malevolent. [Archaic or R.] And worse than death, to view with hateful eyes His rival's conquest. --Dryden. 2." It seems that this poem is really to express a great dislike, hatred towards someone or a certain situation that they are in. I wonder what is Suetsugu trying to portray in this chapter for Taichi? |

CuebeeMar 17, 2017 6:20 AM

| *Yawn* Not gonna argue again with a stupid troll. |

Mar 17, 2017 6:44 AM

#5

Cuebee said: Just wanted to talk about the poem from chapter 179 that took my interest. "The rooster's crowing In the middle of the night Deceived the hearers; But at Osaka's gateway The guards are never fooled." As for my understanding, this poem contains a lot of bitterness, but I could be wrong so I looked for other opinions about this poem. One of them is from http://essaychief.com/research-essay-topic.php?essay=2364453&title=Analysis-Of-hateful-Things-By-Lady-Sei-Shonagon "The rooster's crowing In the middle of the night Deceived the hearers; But at Osaka's gateway The guards are never fooled. Hateful Hate"ful, a. 1. Manifesting hate or hatred; malignant; malevolent. [Archaic or R.] And worse than death, to view with hateful eyes His rival's conquest. --Dryden. 2." It seems that this poem is really to express a great dislike, hatred towards someone or a certain situation that they are in. I wonder what is Suetsugu trying to portray in this chapter for Taichi? It's interesting, but also because the story is about someone who wanted/tried to escape that he tried to fool everyone but in the end he wasn't able to escape, that's why he couldn't help but feel hatred towards his rival/enemy or the person who trapped him that made him unable to escape. |

|

Mar 17, 2017 6:58 AM

#6

| I thought it could be much simpler, more like the content of the poem is corresponding to what is happening. The content of the poem in simple words: A person is faking a rooster's cry to deceive the gatekeepers. Osaka gatekeepers don't buy that = they understand that the rooster's cry is fake. Taichi is faking swings to deceive his opponent. The moment he sends this card to Tamaru we see that Tamaru realizes what is going on - that it was Taichi faking his swings. So I think the poem is mirroring what is actually going on in the last pages. A person faking the rooster's cry = Taichi faking swings. Gatekeepers understanding that the cry is fake = Tamaru understanding that the swings are fake. Also, not really relevant, but this poem, #62 is the favorite one for Sakisaka sensei. It is mentioned in 144 chapter :) As for bitterness and hatefulness, as I read your link till the end, the author of the article contemplates about how this hatred in Sei Shonagon's (the author of the poem) essay is actually excessive - at smallest and simplest things :'D The reason Sei Shonagon was so bitter was because the visitor left her with poor excuse. (just in case - these are links where the backstory behind the poem can be found - https://100poets.wordpress.com/?s=62, http://www.heliam.net/One_Hundred_Poems/62_Sei_Shonagon.html ) So the poem is basically a very witty way to say "your excuse was lame" :)) Therefore the bitterness. However, judging by the full text of the article that you posted, the lady in question used to be hateful and annoyed by all the smallest things :D |

Mar 17, 2017 7:05 AM

#7

| @anima_K There was a double meaning in that poem, there was a certain joke that was used which is the story of a Chinese man named Moshokun. The “joke” here is a reference to a Chinese story where a man named Mōshōkun (孟嘗君) was being chased by guards and was trapped inside the city. He came to the famous gate of Kankokukan (函谷関), which was closed for the evening, and imitated the sound of a crow so well, that the guards were fooled and let him out. Sei Shonagon was reminding her husband that this wouldn’t work, so don’t bother (and thanks for being late). So as what Nunnally pointed out, it's about someone who wanted to escape but failed to escape. He was able to fool the guards but not the main person that was his biggest problem. https://klingonbuddhist.wordpress.com/2010/08/27/the-pillow-book-a-review/ And the poet of that poem. Was someone who also have a lot of things she hated in their situation. As for the link I gave you, the blogger talked about how Sei have a lot of things that she dislike because of her situation that nothing she can do about. "Every paragraph in this essay is a situation given by Sei and then criticized. She has many things that she dislikes as she points out in this essay. " Therefore it is not wrong to say that this poem is about a great dislike/hatred, because this poem was based on what the person feel and the message they wanted to express in their poem and since she wrote this poem out of hatred and wanted to express it, therefore this poem is about things that a person hate. If I may add, from the links you gave me, it is said that Sei made this poem and sent it to the person who left her as a way of saying he will not be able to fool her with his lame excuse"The man left with an excuse and wrote her to make another excuse, but she wouldn't get fooled by that, meaning he cannot escape with that lie. Which again prove that this poem is about her "dislike" She dislike the way he left and made this poem for that. So the feeling that the poet wanted to express in this poem is again by what she dislike, her annoyance, her anger, her hatred. So I do not think that this poem is about how Taichi is faking his swings for his opponent, because that's not what the feeling and the message that was written in the poem. But rather a person who felt like she's being fooled, being played at and she doesn't like it. |

CuebeeMar 17, 2017 8:03 AM

| *Yawn* Not gonna argue again with a stupid troll. |

Mar 22, 2017 8:53 AM

#8

Anima_k said: Taichi is faking swings to deceive his opponent. The moment he sends this card to Tamaru we see that Tamaru realizes what is going on - that it was Taichi faking his swings. So I think the poem is mirroring what is actually going on in the last pages. A person faking the rooster's cry = Taichi faking swings. Gatekeepers understanding that the cry is fake = Tamaru understanding that the swings are fake. Hello. I do think that poem was about someone expressing their hatred or angered to someone or situation ( as Cuebee mentioned.) But since you mentioned something that happened from the latest chapter, I think that Taichi sent it to Tamaru as a way to express his annoyance towards him (For what he did) Since it's not like Tamaru did it out of curiosity, but because there was an intention to mess up with Taichi. So it's more like, Taichi's way of saying "You cannot fool me, I know what you're trying to do" |

|

Mar 23, 2017 12:42 AM

#9

| @Nunnally03, could be :) that's why it is interesting to share everyone's opinion, one poem but so many interpretations :) By the way, the dead cards that were read when Taichi made his fake swings: #79 (akikaze ni) See how clear and bright Is the moonlight finding ways Through the riven clouds That, with drifting autumn wind, Gracefully float in the sky. #24 (Kono tabi wa) At the present time, Since I could bring no offering, See Mount Tamuke! Here are brocades of red leaves, As a tribute to the gods. |

Mar 23, 2017 9:27 AM

#10

| @Anima_k Yes the poems in Chihayafuru is a nice thing to discuss. At the present time, Since I could bring no offering, See Mount Tamuke! Here are brocades of red leaves, As a tribute to the gods. According to the commentary in the book I am reading, the poem was composed by Michizane after going on an excursion with his patron, Emperor Uda, and because he had little time to prepare, he couldn’t make a propering offering to the gods for a safe trip. The term nusa (幣) means a special staff used in Shinto ceremonies. But Michizane, admiring the beautiful autumn scene on Mount Tamuke, hopes that this will make a suitable offering instead. Sadly Michizane would be disgraced and exiled only a short time later. https://klingonbuddhist.wordpress.com/2010/07/22/michizane-poem-from-the-hyakunin-isshu/ Michizane's poem suggest that in his hurry to depart, he did not have time to prepare suitable offering for the gods of Mt. Tamuke, but that the natural beauty of the crimson leaves made an excellent substitute. Sugawara No Michizane and the Early Heian Court By Robert Borgen I think this poem is mostly about the lack of preparation. The author of that poem wasn't able to prepare a proper offering to the gods of Mt. Tamuke (for unknown reasons) and instead he wasn't able to bring any offering for them, then he hope that the autumn leaves will be enough as a substitute. In other words. He wasn't able to prepare properly so he just make do with whatever he can offer which he think is beautiful enough. |

CuebeeMar 23, 2017 9:42 AM

| *Yawn* Not gonna argue again with a stupid troll. |

Mar 23, 2017 10:11 AM

#11

| And as for me, what caught my eye was the symbology :) I mean crimson leaves is a famous symbol for Chihayafuru and it was used in the 179 chapter for all the competitors - except Taichi wasn't on those pages. Suetsugu-sensei didn't include him there in the list of those who have passion for karuta. On another side, Taichi also has an individual association with crimson leaves - his love for Chihaya was described as one. I won't try to interpret the poem based on this chapter solely, because I feel like later more context will be available to have a better judgement (just my personal feeling). But for now, what caught my eye is exactly the symbology of crimson leaves (=passion for karuta/love?) being viewed as a suitable offering/sacrifice. |

Anima_kMar 23, 2017 10:28 AM

Mar 23, 2017 10:34 AM

#12

Anima_k said: And as for me, what caught my eye was the symbology :) I mean crimson leaves is a famous symbol for Chihayafuru and it was used in the 179 chapter for all the competitors - except Taichi wasn't on those pages. Suetsugu-sensei didn't include him there in the list of those who have passion for karuta. On another side, Taichi also has an individual association with crimson leaves - his love for Chihaya was described as one. I won't try to interpret the poem based on this chapter solely, because I feel like later more context will be available to have a better judgement (just my personal feeling). But for now, what caught my eye is exactly the symbology of crimson leaves (=passion for karuta/love?) being viewed as a suitable offering/sacrifice. I posted the credits on my posts. If you want to read more about Sugawara no Michizane, I think you can just google search about him but, this book is also about him: Sugawara No Michizane and the Early Heian Court By Robert Borgen I think it's just right to interpret the poem for this chapter if it appeared in this chapter because that's how usually Suetsugu express their feelings or situation... that's why we get another set of poems for the next chapter. I am not sure how to interpret it for the latest chapter..since it's not like I can understand it :D Although Chihaya went through doubts due to lack of preparation, but that was a poem read during Taichi's match, I think? |

| *Yawn* Not gonna argue again with a stupid troll. |

Mar 23, 2017 10:46 AM

#13

| I apologize, it was just written in your post "According to the commentary in the book I am reading" so I thought you are reading a book and wondered if it can be found online. Then I went by the link and understood that it was a quote :'D sorry :) Yeah, I just also have no idea how to interpret it here. And there were times where I could connect poems from one chapter to events later on, so that's why I chose to wait a little. I do think it might be connected with the fact that Taichi was not among those who were pictured as competitors at the qualifiers with leaves falling around them... As for preparation, Chihaya is the only one who lacks preparation, she forgot the bandages, right? And almost overslept... but why would it be connected with Taichi then? I don't know, I'm not sure... Yes, it was the last card read. Taichi did a fake swing on Akikaze ni, then on this one, Kono tabi wa, then sent the Yo komete card. |

Mar 23, 2017 11:09 AM

#14

| @anima_k The book "100 Poems from the Japanese" by Kenneth Rexroth is actually good if you want a better translation for the Hyakunin Isshu. I personally love that one. #79 (akikaze ni) See how clear and bright Is the moonlight finding ways Through the riven clouds That, with drifting autumn wind, Gracefully float in the sky. That poem talks about a very very beautiful moon that you can see through the gap of the clouds that was brought up by the autumn wind. The moon that was hidden behind the clouds wouldn't have been seen if not because of the autumn wind. |

|

Mar 24, 2017 2:46 AM

#15

| @Nunnally03 That's how I also see it, I wonder tho on what message is Suetsugu trying to express in that poem for this chapter? Autumn represents passion in this manga Moon is often depicted as something lonely But the author of that poem wrote it in amazement while watching the moon and the people. But it is said that Taichi faked his swing on that card. |

| *Yawn* Not gonna argue again with a stupid troll. |

Mar 24, 2017 9:38 AM

#16

| @Cuebee I think it depends on the context. According to: A Hundred Autumn Leaves: The Ogura Hyakunin Isshu: " Autumn is the most picturesque of all the seasons in Japanese poetry, along with Spring. In both cases of Autumn and Spring, we find a sense of melancholy and feeling of being forsaken prevails in the tone of the poems." Example: In the mountain depths, Treading through the crimson leaves, The wandering stag calls. When I hear the lonely cry, Sad--how sad!--the autumn is. And from: One Hundred Leaves: A new annotated translation of the Hyakunin Isshu Autumn is a symbol of loneliness, of the bright and warm part of the year coming to and end. Likewise, an autuman breeze symbolizes sadness. In contrast, spring symbolizes youth, love and vitality. Time of day is important too. For example, dusk is a symbol of sadness. Another example are poems that do not mention directly waiting for a missing lover overnight; rather they might mention seeing the morning moon alone. On the other hand, Winter is associated with the feeling of being forsaken and left,alone, the typical imagery for winter is haze, snow storm, frost, and the colour white. Something I would like to add about the poem Chihayaburu The metaphor of the flowing of the river dyed in red refers to the imparting of the feeling of love unto his lover by him or perhaps vice-versa, and then he used another rhetorical device of ancient poetry, a divine or rather a metaphysical comparison. He says, "even when the gods held sway in ancient lands" he want to immortalize his love and claim it as uncomparable in all history and even in the divine world. |

|

Mar 24, 2017 10:35 AM

#17

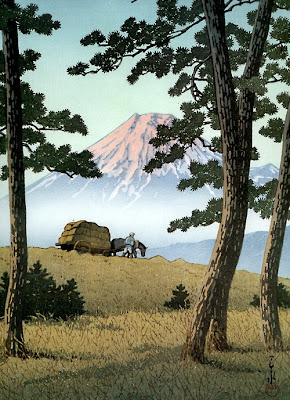

| @Nunnally03 Thanks! On the other hand, Winter is associated with the feeling of being forsaken and left,alone, the typical imagery for winter is haze, snow storm, frost, and the colour white. Probably the reason why Sou was often associated with the Mt. Fuji, since Mt. Fuji is the highest peak on Japan (while the Meijin title is on the highest position for a karuta player) And why they often depict Mt. Fuji's top covered in snow when they are talking about how lonely the ones on top might be, for being alone. Which makes me wonder again on why Mt. Fuji has been covered in black from the past chapters. =======UPDATED======== About Poem 4 田子の浦に打ち出でてみれば白妙の 富士の高嶺に雪はふりつつ Tago no Ura ni Uchi idete mireba Shirotae no Fuji no takane ni Yuki wa furi tsutsu When I take the path To Tago's coast, I see Perfect whiteness laid On Mount Fuji's lofty peak By the drift of falling snow.  Stamp from Yoshiwara station, which is the closest railway station to Tago no Ura Bay. And there he is, Daruma san! Yoshiwara-juku (吉原宿, Yoshiwara-juku) was the fourteenth of the fifty-three stations of the Tōkaidō. It is located in the present-day city of Fuji, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan. The Yoshiwara-juku Festival is held each year in October and November in Fuji, showing visitors the area's history. Yoshiwara-juku was originally located near the present-day Yoshiwara Station, on the modern Tōkaidō Main Line railway, but after a very destructive tsunami in 1639, was rebuilt further inland, on what is now the Yodahara section of present-day Fuji. In 1680, the area was again devastated by a large tsunami, and the post town was again relocated and moved to its current place. Although most of the route of the Tōkaidō in Sagami and Suruga Provinces was along the seashore as the name "East Sea Route" implied, at Hara-juku travelers walked away from the sea. Also, up until this point on the journey, Mount Fuji could always be seen to the right of the travelers coming from Edo. However, as they traveled inland, they could see Mount Fuji to their left, and the view came to be called "Fuji to the Left" (左富士, Hidari Fuji).   During the Edo period, there was a long colonnade of pine trees lining the route along this point. This is depicted in the classic ukiyoe print by Ando Hiroshige (Hoeido edition) from 1831-1834 which shows a groom leading a horse with women travelers down a narrow path lined with pine trees with Mount Fuji to the left. all from: https://traveloguegokuraku.blogspot.com/2012/05/tago-no-ura-bay.html ********************************************* This reminds me that the only poem in Hyakkunin Isshu with Pine trees being mentioned is the Tachi Wakare, which also happened to be Taichi's namesake card and from the past chapters,. we saw how Chihaya went to Toudai to get the USB from Sou... and Taichi saw her (Although he ran away) Then later on Sou and Chihaya meet again, next we saw Sou with Taichi again. I wonder if it's the same as this? I wonder if Taichi may one day connect Sou and Chihaya? Because it's almost as if, looking at Mt. Fuji is connected to the path with pine trees. or something more else, probably a sign for Arata and Taichi being the rival? like.. "before you get to the top, you have to pass me by first." |

CuebeeMar 26, 2017 5:52 PM

| *Yawn* Not gonna argue again with a stupid troll. |

Mar 27, 2017 5:48 AM

#18

| @Cuebee I think it's more like about how...seeing the "real beauty" of the mountain even from afar, in that path. Because the passerby were able to see and admire Mt. Fuji even though they were far from it, while walking down that path. If you will relate it to the manga, then it's probably the same on how Taichi may help Chihaya and the others into understanding Sou. That he's not as bad as what everyone thought of him. Chihaya have always thought of Sou in negative way and never did she and Sou had a talk after he told her she wouldn't become a Queen and made her feel bitter about it. But there, she went to Toudai to ask for the USB. Why would she do this when she didn't even had a chance to talk to him, but suddenly her bitterness is gone and she's asking for the USB? Because of Taichi. Then even after he told her coldly that he wouldn't give her the USB and called her naive, we didn't see a tiny bit of bitterness and she still treated him normally. Chihaya realized, that Sou isn't as bad as what he is because Taichi wouldn't stay with him if he is. So maybe that's how it will also goes with the rest. |

For salty fans For salty fans |

Apr 10, 2017 8:42 AM

#19

If it's symbolism,there was a page where all of the karuta players are shown with autumn leaves flowing on them. Taichi is not included in that panel. And we all know how autumn leaves symbolize passion in this manga. The other about bringing his offering, the brocade of red maple leaves. What do those leaves mean here? If you are talking about the poem 24 which is actually a dead card. I think it is best for you to remember on how they see "dead card" in this manga as something negative, not good, bad omen. Even the poem akikaze ni is a dead card. Both of the poem you used as a symbol is a dead card. Except the one he sent which is poem 62 which symbolizes hatred and annoyance. So if we are going to talk about poems as symbolism in this chapter, then I think you should also put into account that those cards you mentioned were dead cards which isn't a good omen. I wonder what it means with those cards being dead cards instead? |

|

Apr 14, 2017 11:44 PM

#20

| In Chapter 180 Setsuna Hayami makes her reappearance with a slightly more expanded introduction to her back story. Once again she and her calligraphy based karuta are associated with 尾形光琳 (Ogata Kōrin) (Kourin, Korin) or -perhaps more precisely- associated with reproductions of karuta sets based on Kōrin's writing and illustrations. These cards as depicted present something of a puzzle to me. In flashbacks in chapter 180 we are shown that Hayami too attempts to reproduce them by hand and it appears that one of her attempts could be for "natsu no yo ha" (36), Mostow: "The short summer nights". When Hayami made her first appearance she was also depicted with cards from a Kōrin set. Based on images on the manufacturer's site, it looks like the following cards appeared in Vol. 29, Ch. 149 on page 15, top to bottom: 1. Poem 60 - Torifuda 2. Poem 10 - Yomifuda 3. Poem 60 - Tori 4. Poem 36 - Tori 5. Poem 60 - Yomi 6. Poem 10 - Tori 7. Poem 72 - Yomi 8. Poem 72 - Tori 9. Poem 36 - Yomi 10. Poem 10 - Tori Where both the playing and the reading cards for poem 36 may have been depicted alongside Hayami. Perhaps someone more familiar with the sets of Kōrin cards comes along to provide correct(ed) identifications. Something else to note about that richly decorated panel is that the text of another poem, "tama no o yo" (89) is written over the top of all the imagery. Written in the same "script" or calligraphy style as employed for the Kōrin card set. Shokushi Naishinnō's poem is not depicted as a card, however. Its text appears unlike the other poems because it is shown free floating without its illustration from that set. To repeat something about that chapter from another forum, I found Hayami's one stroke introduction interesting and the allusion, in that same panel, to a "black and white world" intriguing. Intriguing not in the least because it came right after all the references to that painter / artisan perhaps best known for his use of vivid colour. |

removed-userMay 3, 2017 9:15 PM

May 3, 2017 9:13 PM

#21

| Setsuna Hayami first appears past -what is probably- the midstream point of this story. We have no idea when Hayami was conceived by Suetsugu-sensei as a character. Nor do we know if -and if so, how- any of the elements, the characters, in her name were considerations for the creator of Chihayafuru. Precedent suggests they were. Wiktionary has the following to offer, posted as a point of departure, for further exploration: Setsuna (刹那) is a Japanese word meaning "a moment; an instant". The word came from a Buddhist term: せつな meaning "split second," which was imported from China (in Chinese character format: 刹那 chànà) but originated in India (in Sanskrit: क्षण ksana). It can also be used as a given name as-is, or with different kanji. That is a very important homophone for Setsuna, in my opinion, but Setsuna Hayami’s name is indeed written with different kanji. Used to produce the sound of her name. As ideograms those characters have different meanings. Names are rarely translated inside translated texts but I think the original spelling often matters so I’m going to belabour this point because it connects to earlier points about not letting the original language go missing. Corrections and additional comments welcome…速水 節奈 はやみ せつな Hayami Setsuna Next to split her name into Individual kanji, using primarily one online dictionary: http://jisho.org 速 haya: quick, fast Readings: Kun: はやい (hayai), はや- (haya-), はやめる (hayameru), すみやく (sumiyaku) (which has its own homophone connection because of sumi which may lead to 墨 sumi, meaning ink) On: ソク (soku) 水 mi[zu]: Kun: みず (mizu) 1. water. (especially cool, fresh water, e.g. drinking water. Note that warm and hot water are not readily associated with Mizu in Japan(ese). 2. fluid (esp. in an animal tissue) 3. flood; floodwaters 4. water offered to wrestlers prior to a bout - Sumo term. 5. break granted to wrestlers engaged in a prolonged bout 6. water. water is a chemical substance with the chemical formula H2O… etc 水 On: スイ (Sui) 1. Wednesday 2. shaved ice 3. water (fifth of the five elements) 節 Setsu: node, season, period, occasion, verse, clause, stanza, honour, joint, knuckle, knob, knot, tune, melody Readings 節: Kun: ふし(fushi), -ぶし (bushi), のっと (notto) On: セツ (setsu), セチ (sechi) 奈 Na: what?, Nara. Obsolete translation: Apple tree. Readings 奈: Kun: いかん (ikan), からなし (karanashi) On: ナ (na), ナイ (nai), ダイ(dai) Mentioned in the Wiktionary as a variant of 柰 (uncommon “Hyōgai” kanji) Which itself means: To bear or endure, a crabapple tree It has the same On & Kun readings The “haya” in Hayami sounds the same as the “haya” in Chihaya, but in Chihaya’s name it is written with a different kanji (早). There is a similarity in the meanings too, however, perhaps importantly, with some difference in nuance. Through that part of their names they might both be connected to each other and in turn to the “se o hayami” poem (77). In the poem, hayami is often written in kana: はやみ In Setsuna Hayami’s case there is also, possibly, an additional link to that poem, through the Se in her first name. With the note that here too the spellings differ. The parts of her name, if you divide them, are Setsu and Na, based on the kanji, or せ つ な Se Tsu Na when written in kana or romaji, as Morae and/or as syllables. In the case of spelling out the poem it is even more complicated because then we’re dealing with more than one ancient Japanese language, no longer in use, and a modern Japanese language used as approximation of the original written text, extant in different formats. All more or less wide open to re-interpretation and subject to transliterations during the time it was composed and in the centuries which separate us from the poet. In “se o hayami” - Se as 瀬 can also be written as 湍 -without changing the meaning- the latter of the two kanji can, through different radicals, also be linked to the first kanji in 湍沢 (Mizusawa). The 瑞 or Mizu in Mizusawa differs only in the use of 王 as a radical instead of 氵from the Se which can be used to write Se in “se o hayami” in present day Japanese. This 瑞 also sounds like but doesn't look like this 水 (mizu) and has a different meaning. I don’t know if that played any role in Suetsugu-sensei's choice of characters. I don’t know if “se o hayami” is Setsuna Hayami’s namesake poem either but it is all very suggestive to me, and fun to look into. With the note - probably as redundant as the preceding notes - that in Japanese Hayami’s name wouldn’t appear in that order all that often. A "file" like this can be constructed for every character's name. In Japanese as in any other language the meaning of names can sometimes be discerned at first glance but in every day use we don't pay much attention to that aspect of names. Mrs. Baker may have nothing to do with bread. Mr. Miller may have no connection with Don Quixote... but ... Hayami may serve as a reminder that we may have to go back to the very beginning, to the very words chosen to represent the series and to the characters picked at inception - without guarantees that the meaning given -or assumed- at the start matches the meaning in the end. Sometimes that may mean going back to the very basics of the language in which these words were first composed. Suetsugu-sensei loves playing with words. On that I think we can all agree. In the OP for this thread Cuebee wrote: “Chihayaburu - as we all know, Chihayaburu is about a passionate and unchanging love.” It is no doubt a figure of speech given the rest of Cuebee’s introduction and Cuebee's invitation to explore and to offer differing interpretations but I want to address that line briefly as an after thought to the comment about Hayami because I’m not sure we all know that’s what “Chihayaburu” is about. Nor am I at all certain that’s what Narihira’s poem was about either. Neither, for that matter, am I convinced that the preexisting pillow word rests on that meaning. Originally or in the universe created under this title by Yuki Suetsugu. A universe she has since expanded and which she probably understands better now than she did when she first started developing the idea for this manga. But not necessarily. It would be odd though if she stopped reading and examining poetry in the years this series has run now. We may settle what the title word means and what that specific poem means in the context of her Chihayafuru story but we won’t settle the meaning Narihira had in mind. The poem itself starts with the fascinating reality that it may, at its very basic, either depict a river, the depiction of a river or both. As the headnote attached in poetry anthologies suggests. As its placement in the autumn section of poetry anthologies suggests. There may be no more to it than that. Despite Ki no Tsurayuki’s observation that there is too much meaning in Narihira’s poetry. It may be about no more than that. Drawings resembling red leaves as though floating on the surface of a river. Why should we take 大江奏's (Kanade Ōe’s) word for it that there is more to it than that? The word and the poem have taken on their own connotations in the context of the series. It may well represent passion and that may well apply primarily to Chihaya whose name sake card it became. Chihayafuru is not the only poem with which she is associated nor is the Chihayafuru poem only relevant to her. She shares not just that one with other characters either. It would be a mistake, in my opinion, to single them out to the point of isolation... and that is clearly not the objective of this thread, nor this series. Can we agree on that as well? Setsuna Hayami can be treated as the boulder or rock(s) of the "se o hayami" poem. A temporary obstacle in the way of the fast flow of its water. Momentary but ultimately insignificant obstruction before the flow moves into more meaningful territory again. What a waste it would be to give such an interesting character such treatment. Fortunately quite a few people have paused here in these instants devoted to her. Earlier I wrote: "In Setsuna Hayami’s case there is also, possibly, an additional link to that poem, through the Se in her first name. With the note that here too the spellings differ." In 綾瀬千早's (Chihaya Ayase's) case the connection to that poem through Se is perhaps more direct, in "modern" Japanese spelling. The kanji in Chihaya's family name includes this 瀬 which is not only pronounced but also spelled the same as the Se of "se o hayami", in a modern spelling. A poem which became the seventy-seventh in Teika's Ogura collection and the first we ever see Chihaya take during a karuta match, not counting the anachronistic flash forward at the very beginning of the story. |

removed-userMay 6, 2017 3:54 AM

May 5, 2017 9:45 PM

#22

Cuebee said: So this is the English translation for Chihayaburu: "Even when the gods Held sway in the ancient days, I have never heard That water gleamed with autumn red As it does in Tatta's stream" I think this translation may be from the transcripts of "Ogura Hyakunin Isshu" as hosted on the UVa website. http://jti.lib.virginia.edu/japanese/hyakunin/index.html Transliterated into modern Japanese it looks like this there: Kanji and kana: 在原業平朝臣 千早ぶる 神代もきかず 龍田川 からくれないに 水くくるとは Romaji: Ariwara no Narihira Ason Chihayaburu Kamiyo mo kikazu Tatsuta-gawa Kara kurenai ni Mizu kukuru to wa Where the poem comes with its own -curious- illustration: http://jti.lib.virginia.edu/japanese/hyakunin/images/onna17.jpg To return to the very beginning, as in the first panels of the manga and the OP of this thread. It does all start with this particular "Chihayaburu" poem. The one composed by Narihira. If we skip the first panels leading up to the first images of a karuta match in progress. The first "syllable" recited and the first card we see flying is the playing card for that poem. The card doesn't fly by itself and the moment is out of sequence but let's skip that too for now. In your subsequent comments you've at times included images. To illustrate a point about the "tago no ura" poem, for example. In the collected volumes of "Chihayafuru" the "Chihayafuru" poem is also printed on the inside flap of the dust jacket. Before we even get to the story we're already made aware of that poem. To back up a little further, we can also try to find images depicting the earliest extant examples of Ariwara no Narihira's "Chihayaburu" poem in writing. UVa also hosts a modern Japanese transcript of the "Kokin Wakashū" or "Kokinshū": http://jti.lib.virginia.edu/japanese/kokinshu/kikokin.html The Wikipedia article for that poetry anthology includes links to scans of pages from a "Kokinshū" copy as preserved by Waseda University. Narihira's "Chihayaburu" poem was included in that collection, along with commentary in the kana introduction, I paraphrased above, attributed to Ki no Tsurayuki.* Poem seventeen is poem two hundred ninety four in "Kokinshū". It was included in the fifth book, the second of two sections of poems devoted to the autumn season. In that Waseda scan, the poem and its attribution to Narihira looks like this: http://archive.wul.waseda.ac.jp/kosho/he04/he04_05284/he04_05284_p0058.jpg The preceding page in that scanned copy has one of Sosei's poems "Momijiba no", poem 293 in Kokinshū (the poet of "ima kon to" (Uva), poem 21 in Teika's Ogura collection) and the headnote which 293 shares in anthologies with Narihira's "Chihayaburu". Helen McCullough provides the following English translation of that shared headnote for the poem in "Kokinshū", quote: “Composed when the Nijo Empress [Koshi] was still called the mother of the Crown Prince. Topic set: a folding-screen picture of autumn leaves floating on the Tatsuta river.” From: McCullough, Helen Craig (1985). Kokin Wakashū: The First Imperial Anthology of Japanese Poetry. Stanford University Press. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kokin_Wakashū Appropriately, for a topic like this, there are different ways to read the title of the thread. “Chihayafuru poems” can mean: “Different poems in the Chihayafuru story” and it can also mean different “Chihayafuru poems”, i.e. different poems titled or starting with the word “Chihayafuru”. Another bit of redundancy, used as an opportunity to back up even further. “Chihayaburu” has been identified as one of the Makurakotoba, or pillow words, employed in Japanese poetry. Using Wikipedia as a starting point again and going from the connection made there to Man'yōshū. In the table with examples of Makurakotoba it says that the pillow word Chihayaburu means powerful/mighty and that it modifies the place name Uji and the word or concept kami ‘gods’. Suetsugu-sensei had, in particular, Kana-chan elaborate on that element of Chihayafuru. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Makurakotoba Used to make the point, perhaps also redundant, that Narihira wasn’t the only one, nor the first to use “Chihayaburu” in a poem. When searching the eTexts on the UVa site for ちはやふる or ちはやぶる it returns quite a few different poems, beginning with those terms, in the different sections or books of Man'yōshū, an anthology linked in an earlier comment. Fu ふ and Bu ぶ are perhaps the most common spelling variations in Chihayafuru ちはやふる but Suetsugu-sensei doesn’t always use only kana or the exact same spelling either. From time to time she’ll use kanji to spell out Chihayafuru in a different way in her manga. Two examples: 千速振る 千早ふる * McCullough offers the following English translation for the line about Narahira in the Kana Preface of "Kokinshu": "The poetry of Ariwara Narihira tries to express too much content in too few words. It resembles a faded flower with a lingering fragrance." Another noteworthy line from that fascinating Kana Preface addresses the poetry of Ono no Komachi, about whose work the author of the Preface wrote these concluding words: "Its weakness is probably due to her sex". We can wonder what Kana-chan thinks when she reads something like that. Perhaps gender divisions are still maintained in the most prestigious Karuta competition due to lingering sentiments like these. Perhaps Suetsugu-sensei has some point to make in that regard as well by setting up the ongoing story from now on from the preliminary rounds of the -segregated- national championships. The road to 若宮詩暢 (Shinobu Wakamiya) at 近江神宮 (Omi Jingu). Presumably the hand in that panel, the animators decided to omit in their adaptation. The only other playing card with visible text:「もれいつる つきのかけ のさやけ・」- transcribed in the margin on the two page spread in the bi-lingual edition as: "More itsuru tsuki no kake no sayake" - in that panel has been mentioned in this thread a few times already. The reader besides holds a reading card while one additional playing card, depicted below the ちー Chi・・・, faces away from us, with only its double leaf motif exposed. With a WHAM! topping it off, above the spotlights and the two -seemingly detached- observers. |

removed-userMay 6, 2017 5:57 AM

May 9, 2017 2:36 AM

#23

| Continuing here from several other threads... Descriptions of the Nike Samothrace statue alert us to an other element of speculation about the characters, the story and Suetsugu’s intentions for all of them as well. How much do we need to know about the referenced objects and texts? How much must we assume the mangaka knew about them before incorporating such materials into her own artwork? H.W. Janson, about the winged victory statue in “The History of Art”: ”The goddess has just descended to the prow of a ship. Her great wings spread wide, she is still partly airborne by the powerful head wind against which she advances. The invisible force of onrushing air here becomes a tangible reality. It not only balances the forward movement of the figure but also shapes every fold of the wonderfully animated drapery.” Perhaps we can compare Suetsugu to Hokusai (1740-1849), arguably the most recognisable Japanese artist, who - forgive the pun- liked making waves and who chose to depict the hundred poems in his own manner, in a style contemporary to his own era, in his famous but enigmatic wood block series “Hyakunin isshu uba ga etoki 百人一首姥がゑとき” Hokusai, as Ewa Machotka notes in “Visual Genesis of Japanese National Identity: Hokusai's Hyakunin Isshu”, providing me an opportunity to link back in with the previous comments about spelling in the introduction of Hayami, Hokusai employed various forms of writing for words like uba. Leaving us with a puzzle of interpretation of his attempt at -often obscure and textually unexplained- pictorial re-interpretation from a perspective few before him had attempted. Machotka’s observations, in chapter five: “Manipulating the Canon: Focus on the series title”, begins her exploration of: “The second element: uba”, as follows: "In Hyakunin Isshu uba ga etoki print series Hokusai decided to disguise himself behind a narrator. It is possible to assume that the artist was aware of the unique relations between the anthology and its female audience as he nominated a woman - uba - as narrator of the process of visual translation of Hyakunin Isshu poems. But to understand Hokusai’s choise it is important to know who is referred to by the word uba and how uba influenced Hyakunin Isshu poetry presented by Hokusai in his picture series?" I’m skipping forward here, to name drop Ki no Tsurayuki - again - because he too is said to have assumed the guise of a woman when he wrote the, anonymous, "Tosa Nikki", often attributed to him. He is referred to as its author in one of the "Chihayafuru" panels when Kana-chan mentions her preference for a different one of his poems than the one Teika included in the Ogura collection. To return to imagery associated with Narihira’s poem, an online reproduction of Hokusai's interpretation can be found on the website of The British Museum, here, and the possibility, raised elsewhere that the poems aren't necessarily incorporated to introduce and explain the characters, but perhaps the other way around. The possibility exists that the characters in "Chihayafuru" exist to introduce a new audience to the poetry. By making the characters look like ourselves, as Hokusai did in the Edo period with people in his own time, by making the setting of the -by then already ancient poem- the world around him rather than what the world may have looked like when Narihira composed the poem and in turn looked back to more ancient times in his choice of words. |

removed-userMay 10, 2017 4:03 AM

More topics from this board

Poll: » Chihayafuru Chapter 145 DiscussionClawViper - Apr 25, 2015 |

15 |

by otakuweek

»»

Oct 7, 6:12 AM |

|

Poll: » Chihayafuru Chapter 144 Discussionusagi_Kuro99 - Apr 8, 2015 |

12 |

by otakuweek

»»

Sep 11, 5:21 AM |

|

Poll: » Chihayafuru Chapter 205 Discussion ( 1 2 )Stark700 - Dec 7, 2018 |

81 |

by hopelesspotato

»»

Aug 20, 10:13 AM |

|

» Just finished reading the mangaCawambar - Aug 13 |

7 |

by emiliocylan

»»

Aug 14, 2:53 AM |

|

Poll: » Chihayafuru Chapter 142 DiscussionJakerams - Mar 8, 2015 |

20 |

by otakuweek

»»

Jun 29, 7:36 AM |