What defines good and evil? Who decides which is which? How should evil be dealt with? Death Note does not necessarily answer these questions, but it doesn't intend to—the point is that such questions have been asked for centuries and will never be answered. The show pits formidable personalities with wildly different worldviews against each other, and none of them are afraid to say "I am justice!" The question of who is right haunts every character and ultimately goes unsolved. Let's see if we can't get to the bottom of it, using the three characters at the center of the show's moral conflict.

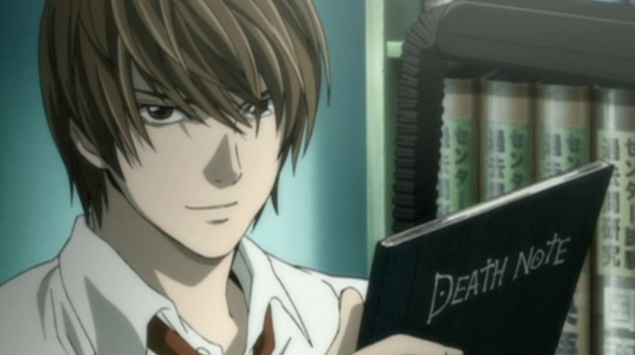

Light Yagami

A protagonist is not necessarily a hero. Light proves this in the first episode. It's not enough for him to take a stand against violent crime; after only five days with the Death Note he's written hundreds of names and declared himself the "god of the new world," vowing to strike down any who stand in his way. It's a noble cause, but easily corruptible; it only takes one more episode for Light to kill someone out of pure vanity.

It's worth noting that in the five years of Light's reign as Kira, the crime rate plummets and all wars are put on hold. From Light's perspective—and that of millions of others—it's one step closer to an ideal world. But a world governed by altruism is a far cry from one governed by fear. By this time Light and his subordinates have started killing pickpockets and other petty criminals, judging mankind on acts rather than reasons. The rule of law rests entirely in the hands of three flawed individuals.

Perhaps only fear can motivate humanity to coexist so completely and so quickly, but the second season makes clear that Kira has addressed symptoms and not causes. Fear, ignorance, and anger still exist, and Light is perfectly willing to manipulate these flaws in his favor, as when he organizes a bloodthirsty mob to storm the Kira task force's headquarters. And lest we forget greed, this same mob is distracted and neutralized when Near showers them with the remains of L's fortune to cover his team's escape.

Remember: Light's original motive is boredom. "Day in and day out, the same news on permanent repeat," he laments, shortly before picking up the Death Note and changing the world forever. Though he vows to strike down the wicked, he makes no distinction between hardened criminals and those "who are less guilty but who still make trouble for others." The troublemakers are culled through disease and accidents, while the truly terrible serve as examples. One could argue that Light's power gives him the responsibility to reshape the world for the better, but the world he seeks to create is unquestionably in his self-centered image.

L

Tsugumi Ohba has described L as "slightly evil", and it isn't difficult to see why. As the undisputed king of detectives, L has essentially limitless jurisdiction and resources. In a world that turns on the interpretation and manipulation of data, he is as close to superhuman as one can get. It's the perfect recipe for a villain: wholly without rivals, with every eccentricity tolerated and every command treated as gospel. Oh, and he's a star athlete. With the ability to succeed at seemingly anything he does, why does L devote himself to law?

In a way, L is just as vain as he proves Light to be in the second episode. He admits that he's "childish and hates losing," which indicates a certain amount of pride at stake in his work. He also will not take a case unless at least ten lives or a million dollars are on the line. If his detective work is indeed just a game to him, it makes sense that he would seek out challenges. He may also believe that his intellect is wasted on any but the most dangerous and impossible cases.

But both he and Light declare "I am justice!" at the end of the second episode. The parallel is no mere dramatic flair. As Misa's extrajudicial kidnapping and torture proves, both men are willing to go to extreme lengths in the name of their principles. But while they both work from the shadows, L has an existing legal framework on his side—one that he is more or less free to dictate. While he insists that extraordinary foes require extraordinary actions, he's also not above outright lying—everything from using convicts as expendable decoys to insisting that his trademark crouch increases his reasoning abilities by 40%.

Humans are inquisitive by nature. We want answers, and Light's tenure as God proves that many of us look up to powerful figures who claim to have them. Light appeals to an innate desire for justice in all people, and uses that to rule the world from the shadows. But his arrogance consumes him throughout the second season because he has no equal to keep him humble. It's possible that L is the same way: he gravitates toward law, detective work, and justice simply because he has to succeed. Where Light represents individual, retributive justice, L represents law at its most perfect and least merciful. As long as he aligns himself with what people consider to be right, who would dare to stand in his way?

Ryuk

While we're on the subject of L, why does the discovery of shinigami shock him so deeply? Because the supernatural upsets the balance of the hierarchy he has crowned himself king of. Gods of death operate by completely different rules than humans, physically and psychologically speaking. Once he's acknowledged that he's dealing with forces beyond his understanding, of course, the shinigami are just one more challenge for him to fit into his worldview.

So what is there to understand about Ryuk? Of all the characters in Death Note, Light's companion shinigami is the most honest. Like Mephistopheles in Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus, Ryuk may be deliberately evasive or obtuse, but unlike the humans he meets, he never tells an outright lie. His reason for dropping the Death Note into the human world is clear from the beginning: "I did it because I was bored."

Is it evil to allow a deadly weapon to potentially fall into evil hands? Perhaps, but would you call gun shop owners evil? All they do is respond to the demands of an existing market. The difference is that Ryuk knowingly attempts to stir up trouble—the most "interesting" humans are the ones who make extensive and creative use of the Death Note, and those who rise to challenge them.

But even then it's difficult to call Ryuk's actions evil. Shinigami are a different race from humans, governed by utterly alien laws and morals. Their continued existence revolves around taking lives, because that is their entire purpose. Humans are essential to their existence and at the same time tangential, representing only a means for survival. Concepts like justice have little meaning to gods of death, because their culture is not built on overcoming adversity or inequality. They simply exist and pass the time, and creatures whose limited life spans drive them to passion are fascinating to them.

Ryuk sets in motion the deaths of thousands—perhaps hundreds of thousands. But he does not hide behind ideals or principles. There will be other lives, and as long as they do interesting things—and give him apples—he is content to watch them destroy each other. He'll be the first to tell you. It may sound like a paradox, but there's an undeniable integrity to that sort of amorality.

So What?

The answer to the question of right and wrong is that there is no answer. Good and evil are mutable concepts that change with perspective and context, and defining them is a constant undertaking that stretches back as far as recorded history. Both Light and L believe that humanity is fundamentally unchanging, both use that belief for their own gain, and both have different definitions of justice to back it up. Ryuk, as one of a stagnant race, is wholly amoral, but he is under no obligation to be otherwise. Nor does he feel it necessary to disguise his motives—why should he answer to alien laws?

Trying to decide who is on the side of justice—whether they take a side or not—misses the point of this show. The idea that there are sides drives human history and achievement. But in the world of Death Note, those who see beyond the abstractions have the power to manipulate them, for better or for worse.