This article was written by SendPieSenpai and edited by toblyvikku and nirosa of the MAL Articles Club.

Interested in writing or editing for us? Click here!

Unrestrained by demands for source accuracy, original anime provide audiences with a fresh story to learn and new characters to love. Without a manga/manhwa, light novel, visual novel, video game, or even music video to establish it, such works allow animation studios to fully exercise their staff's creativity while partaking in a huge gamble. Although originals are outnumbered by adaptations, chances are you've heard of well-loved series such as Angel Beats! by PA Works, Cowboy Bebop by Sunrise, and Mahou Shoujo Madoka★Magica by Shaft. And these are just a few!

Sometimes we wonder: "Wouldn't it be great to be able to make anime?" Afterall, it is just drawing, right? On the contrary—a little bit of research easily illustrates how difficult and tedious it is to create smooth, hand-drawn animation. Deeper research shows that, remarkably, there aren't a lot of English-translated articles or documentaries showcasing the hard work of animators. In the context of original works, this article will go over many of the steps taken in creating our beloved medium!

Story

The writer(s) for original anime have to directly pitch their stories to willing studios. Sources adapted into anime are traditionally chosen by producers due to the source's already proven popularity. With an original, no one knows just how the world will react until that first episode airs. However, having your original story chosen for animation is proof enough that an entire studio believes in your work—that's pretty confidence-boosting!

Character Design

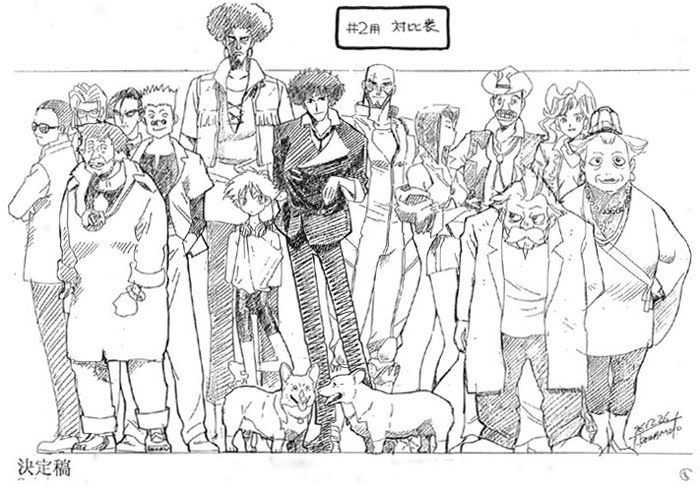

Character design sheet for Cowboy Bebop

An incredible amount of thought and editing (and re-editing) goes into polishing characters who have both recognisable appearances and dynamic personalities. Adaptations get to skip this step entirely. Everything from art style to colour palette—from clothes to motivations: studios must finalise these decisions before any animation work can begin. Characters, after all, make or break every story.

Storyboard

Each scene, each movement of the "camera," and every action animated is outlined by the director in their storyboard. These often undetailed drawings and scribbled notes are how directors communicate their vision and are the basis by which the rest of the team operates. Storyboards are gone over several times—usually by several eyes—before being passed down to the animators. Notable industry names, like KyoAni's Naoko Yamada, first showcase their directorial style upon being chosen as an "episode director," a temporary director who works on only a few episodes of a show.

Keyframes & Inbetweens

Frames used in the making of Kill la Kill

As their name implies, keyframes are the most important frames in an animation and firmly illustrate every change in action. "Keyframers" are capable of accurately portraying the director's storyboards and the team's character designs while showing their own ability to control and understand the flow of the scene. "In-betweening." drawing every frame in-between every keyframe, is typically outsourced or given to freelancers. Every frame is checked thoroughly and redrawn as necessary—inbetweens by keyframers (yellow paper) and keyframes by directors or heads of animation (pink paper). A standard 23 minute, 24 frame per second episode—excluding the opening and ending—can contain over 33,120 frames!

Colouring

Once approved, all of the hand-drawn frames are sent to the colouring department. Given a detailed colour sheet by the character design team, the colourers are tasked with scanning the frames into digital images and filling in the drawings. All 33,120 of them! Mistakes in colours are often due to miscommunication. To save time, the animation team sends the colouring department scenes as they are finished—and not necessarily in chronological order! This is one of the reasons why anime tend to avoid frequent costume changes.

Concrete Revolutio

Set Design & Backgrounds

The appearance of a school. The structure of a city. The forests, the ocean, the clouds. Architecture and the surrounding environments provide an amazing amount of information about the world to the audience! Set designers work more closely with the buildings and cities of an anime, while a typically outsourced art team will work on backgrounds and establishing shots. However, many of the general decisions about setting, such as atmosphere, inspiration, weather, and scale, are made jointly by the director and the original work's creator before any art is made.

Layouts

Layouts from various Studio Ghibli films (clockwise from upper left): Howl no Ugoku Shiro, Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi, Kurenai no Buta, and Mononoke Hime

Like keyframes, layouts manifest the director's vision into more detailed and cinematic representations. Unlike keyframes, these drawings don't appear in the final product. This is because they are only sketches that represent the approximate placement of objects, scenery, and characters shown in the "camera" frame. Compositional tactics from film cinematography—rule of thirds, golden ratio, lead room, dynamic lines—are fully employed in these reference drawings, enabling the animation and background teams to create cohesive and visually-pleasing scenes despite working separately.

CG

CG, in anime, generally refers to any 3D-rendered element. Studios often choose to use 3D CG when there's a scene too complex to hand-draw, such as moving stairs, weaponised vehicles, or complicated structures. This work is always outsourced to a specialised studio where they use 3D modeling/animation programs such as 3DSMax or Maya. Unfortunately, some lag or artifacting is introduced during rendering, a process that requires the devotion of a computer's entire CPU for several hours. In general, the less powerful the CPU, the more the 3D suffers.

Music & Sound Design

When work on an anime's OST begins depends on the ambitions of the studio. The director and producer decide how much freedom they want to give their composers and concertmasters. Some tell these musicians vague emotions or a simple scene description; others give the finished animations as inspiration. SFX are mixed by sound designers who recreate ambient noise into exaggerated, more epic, and louder versions of their realities—from the rustle of leaves to the clashing of swords to the cicadas that haunt all anime summers.

Voice Acting

It's quite obvious what seiyuu do. Like the OST, the time the voice acting is recorded varies. Anime that begin recording early typically intend to use the emotions and facial expressions as a basis for the animation. Anime that start recording during production have the seiyuu time and empathise themselves with the provided video of the storyboard or keyframes. Sitting inside the sound booth behind the glass, the scriptwriter, director, and sound director follow along and listen for anything that may cause misinterpretation.

Cinematography & Editing

When viewers talk about "cinematography" in anime, they are mostly comparing it to its use in live-action films and shows with actual cameras. This is easily understood when said in reviews, but what the animation industry means by "cinematography" is completely different! To anime studios, it means bringing all of the separately-created characters, backgrounds, sounds, and light effects together to complete the scene. Everything is synchronised. Editing is also slightly different from live-action; the anime's director personally goes over every completed scene, changing the playback speeds of certain elements and removing frames as needed.

"Rushes" Check

Even after the innumerable edits done during production, each episode must go through another series of incredibly thorough checks. The industry calls these gatherings of directors and other important staff "rushes" because they occur a week or two before each episode airs. Changes can be made anywhere and can be for anything! The rest of the studio must also "rush" to make these edits so that the main staff's "rushes" are up-to-date and checked again. "Rushes" can take anywhere from several hours to several days, with delays in production ultimately hampering how thorough these checks can be.

Finally, Episode 1 airs and an original anime is brought to the audience as shiny and spectacular as its studio can manage. All of the work seems to have lead to that first showing, but production continues as the weeks between episodes go by. From nothing more than an idea (from scratch!), a beautiful and meaningful animation can arise, its topics, art style, and themes unlike anything the already vast world of anime has seen before. Original works showcase the creativity of curators and the drive of studios to take on hundreds of work-hours to sail far into unknown, untested waters. And we, as viewers, get the gift of seeing something for the first time: no expectations, no spoilers, and a whole new story to dive into.