Let’s be honest – the name of this website isn’t “mymangalist” for a reason. In the West, when we think about Japanese pop culture it’s usually anime that comes before manga. And there’s certainly more money to be made from anime in the West, too (though not as much as there was at the height of the anime boom in the 2000’s). It would be a stretch to say that anime was ever mainstream in the United States – though it’s gotten pretty close in France at times – but stuff like Pokemon and Ghibli certainly achieved a greater cultural penetration than any manga ever did.

So what’s the “difference” between anime and manga? As you can imagine, that’s an incredibly complex and multi-faceted question. In order to answer it, I think it makes sense to begin in Japan – because one has to understand the way the two mediums are perceived differently in their native land to understand the well from which the ideas spring forth. We tend to bunch anime and manga together in the West, which is understandable given how many anime are adapted from manga – but in Japan their role in society is very different.

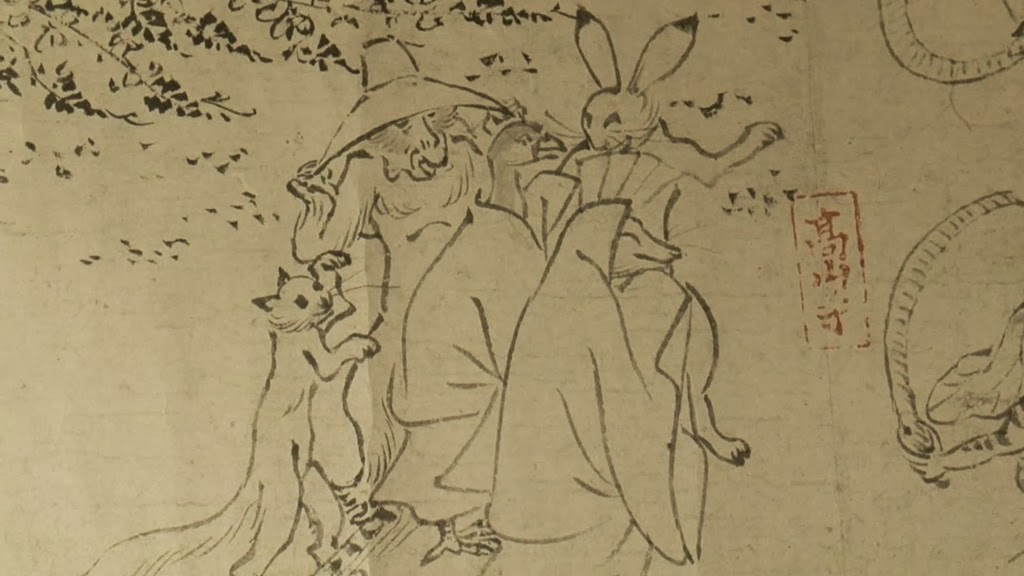

To help understand the fundamental difference between anime and manga in Japanese culture, one might argue that this fact is crucial – there’s kanji for manga (漫画, which, interestingly, literally translates to something like “whimsical pictures”) but for anime one must use katakana (the syllabary generally reserved for foreign words)*. When one understands the huge importance of concepts like “inside” (内 uchi) and “outside” (外 soto) in the Japanese language – something “of us” and something foreign – they understand why this is such an important distinction (while this normally applies to groups of people - natives, family, workmates, friends - it can at least subconsciously extend to concepts and objects as well). Manga is considered a native art form – dating back to the Choujuu-giga, the famous frog, rabbit and manga picture scrolls dating to the 12th and 13th Centuries. They’re housed at Kouzan-ji temple in Kyoto and attributed to the famous monk Soujou Toba (if you’ve seen Kyousougiga you know something of this story).

* Note: There are kanji for anime as well, but they are archaic and by no means in general use.

One of the experiences that stands out to me from my first-ever trip to Japan is boarding the Shinkansen from Tokyo to Kyoto and seeing a very well-dressed businessman in his 40’s or 50’s settle into the seat across the aisle from me, open his briefcase and pull out first a rice ball, then a beer, and finally a copy of Shounen Jump. That was my “Enzo, you’re not in Kansas anymore” revelation – and in the extended time I’ve spent in Japan since I’ve seen Japanese of every social strata, age and demographic reading manga publicly. Simply put, my experience has been there’s no social stigma attached to reading manga in Japan – it’s a well-respected part of cultural life that crosses class, gender and age divides. And my outsider's perspective is that to a large extent, there is a social stigma attached to being an anime fan.

Why is this important? For a number of reasons, many of them directly linked to the creative differences between the two art forms. It’s not a criticism to say that the thematic range of anime is far more narrow than manga. Some of the reasons for that are purely practical (I’ll touch on them shortly), but on a more elemental level, when your audience is the entire country you’re obviously going to have a wide range of styles and subjects (as manga does). When you’re primarily going after a smaller, selective audience willing to pay a lot of money for discs (see House of Pies) that range will be narrower. Simply (perhaps too simply) put, manga’s audience is Japan, and anime’s audience is overwhelmingly a relatively small slice of Japan (children, male otaku, and female otaku). On any given week the top-selling manga might have 500,000 volumes sold (much more if it’s something like One Piece or Shingeki no Kyoujin), while the top-selling anime is usually under 10,000.

The practical side of this diversity gap is equally important. It seems obvious but we sometimes forget that the cost of producing a manga is infinitesimally smaller than an anime series. If a young aspiring author is given a serialization (and this is after a one-shot to test the waters, which anime doesn’t have), it can be cancelled at any time at the cost to the publisher of only a few thousand dollars. An anime must scrounge for funding through a production committee, and once they commit they’re in for the entire series because of the production lag for animation. If it tanks, they’re out a lot of money.

The result of this is that manga publishers are much more willing to take a risk on non-commercial or edgy material than anime production committees. The latter want a hedge – an already-popular source material (be it manga, LN or VN), a famous writer, popular seiyuu, a commercial hook. They want a slice of the pie. While you might see one or two Jousei anime a year these days (and with Manglobe gone who knows if we’ll even see that) there are entire magazines dedicated to Jousei manga. There are manga mags targeted at every demographic group and genre - weekly, monthly, quarterly. Shounen is generally the biggest seller and gets the most attention in the West (with Shoujo second) but they’re only the tip of the iceberg. Anime, by contrast, is almost entirely spread across a much narrower band. There are exceptions (this season’s Shouwa Genroku Rakugo Shinjuu could hardly be a more stark one) but they’re just that – exceptions.

With that said, is one form “better” than the other? To that I would unequivocally answer “no” – they’re simply different. Manga and anime differ in every sense, from the creative process to financing and ultimately to purpose. I do find that as a fan, the balance for me has shifted – at one time I was much more focused on anime, but as my tastes (and the medium) have evolved, I find myself more and more interested in manga. Variety has become much more important to me, and by its very nature manga will always be able to offer more variety than anime.

With that said, there remains a thrill great anime can offer that’s very hard to match. I love the Boku Dake ga Inai Machi manga unreservedly – I was thrilled when an anime adaptation was announced. But seeing it come alive on screen in the superb treatment it’s receiving is an altogether different experience. Anime characters are “alive” in a way manga characters aren’t – we must supply much of the life with our imaginations. The act of embracing these two forms is very different – equally satisfying, but very different. It’s the way in which the anime is able to synch with our imaginations and enhance the experience that separates good adaptations from bad ones.

For me, anime and manga are both indispensable, and it’s their differences that make them so. Each of them gives me something nothing else can (including the other). And it’s when they come together – in an adaptation – that a unique experience as a fan is created.