Jun 27, 2019 2:18 AM

An insight to Yoshiharu Tsuge's publications

As the first Yoshiharu Tsuge’s anthology came out in France, I started creating this blog which will mostly consist of informations from the postscript which I thought could be a good idea for whoever is interested in this author, or even complete some informations included in the future Drawn and Quarterly release. I'll add some of my own thoughts if I deem the informations on hand are not rigorous enough.

For those who would need a bit more informations, Yoshiharu Tsuge is one of the most important authors of Garo magazine along with Yoshihiro Tatsumi and Sanpei Shirato.

He is the creator of a new and avant-guarde genre called watakushi manga or comics of the self where autobiography and fiction blend together in order to create a new form of authenticity. He is also characterized by a reject of entertainment constraints in favor of adult stories breaking off from classical narrative structure in particular with how his stories end abruptly and don’t necessarily resolve the conflict at hand.

We could imagine it took so long for him to accept being published in foreign countries because of how personal his stories were, he mentions in an interview :

You wonder why it took so long?… It’s hard to explain… For a long time I tried to escape other people’s attention. I’ve never liked to be put under the spotlight. I only wanted to lead a quiet life. In Japan we say ite inai, which means living on the margins, not really being engaged with society, trying to be almost invisible if you like.

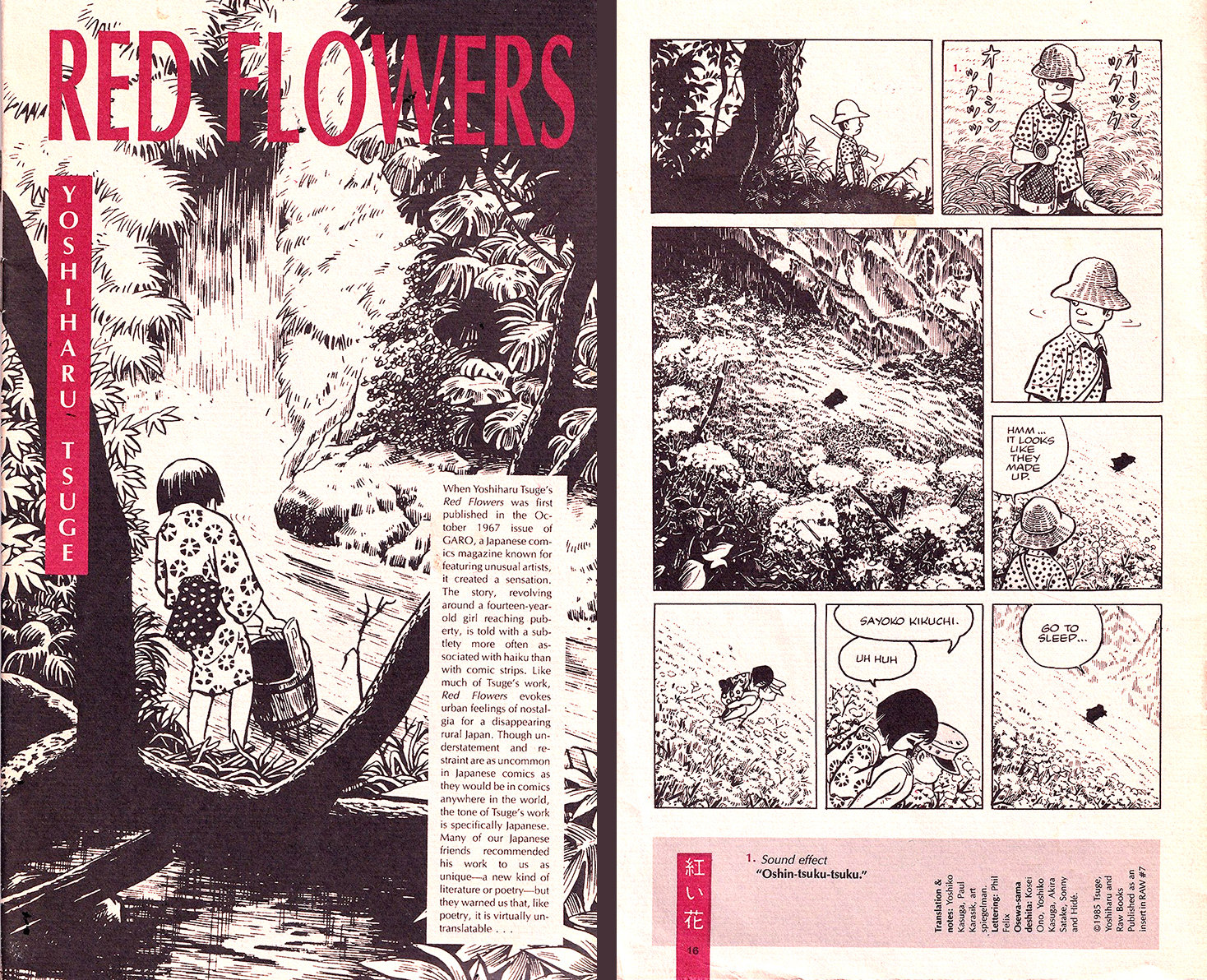

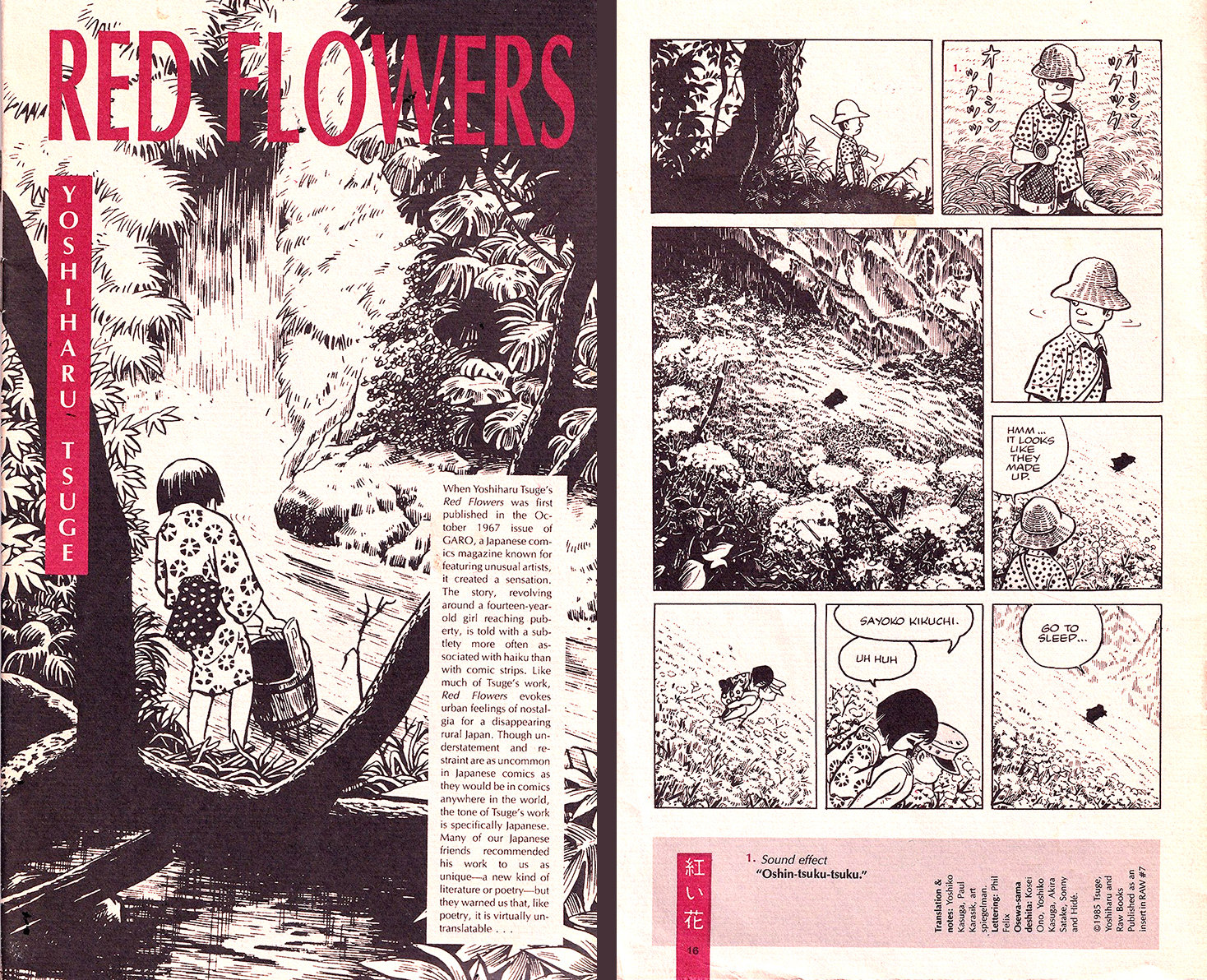

Cornelius (the French editor) first published anthology should be the second one chronologically,

going from march 1967 to June 1968, which basically is the time where his style became more refined after meeting a critical failure and taking a year off to work as an assistant to Shigeru Mizuki. Entitled “Les fleurs rouges” it regroups different stories from Akai hana and Neji-shiki

Chapters included are :

The Wake (Tsuya (通夜) Garo 1967-03)

In Full Sun ( Bessatsu Shonen King 1967-04)

Salamander (Sanshouuo (山椒魚) Garo 1967-05)

Mr. Lee’s Family (Ri-san Ikka (李さん一家) Garo 1967-06)

The Dog of the Mountain Pass (Touge no Inu (峠の犬) Garo 1967-08)

A View of the Seaside (Umibe no Jokei (海辺の叙景) Garo 1967-09)

Red Flowers (Akai Hana (紅い花) Garo 1967-10)

Incident in the Nijibeta Village (Nijibetamura Jiken (西部田村事件) Garo 1967-12)

Chouhashi’s Inn (Chouhachi no Yado (長八の宿) Garo 1968-01)

Futamata’s Valley (Futamata Keikoku (二岐渓谷) Garo 1968-02)

Ondoru House (Ondoru Koya (オンドル小屋) Garo 1968-04)

Mr. Ben’s Snow House (Honyaradou no Ben-san (ほんやら洞のべんさん) Garo 1968-06)

The first chapter The wake is a real rebirth in his career as he acquired more advanced technical abilities when working with Mizuki which allowed him to give life to his visual ambitions, as well as financial stability that allowed him to refuse orders from other magazines and focus entirely on Garo.

He still accepted a final collaboration with Bessatsu Shonen King where he redrew a story created 7 year before. The scenery and characters are a lot more detailed than his forst story published in Garo : as much as Tsuge is known for never having assistants to help him, he asked for the help of Ryoichi Ikegami for this particular story.

This rebirth continues with the Salamander loosely based on the short story by the same name created by Masuji Ibuse (can be read here) . Barely 10 pages long, it perpetuates the genre of dark comedy that started with the wake, it can be noted that it shares similarities with some of Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s stories, most notably with the presence of a dead foetus. It’s from this point that Tsuge starts using internal monologues to characterize the narrator. This subtle change to the first person narration is important enough to be noted when many gives him credit to be the father of autobiographical manga – this change can be compared to the inclusion of direct narration in Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield which created a rupture in the way of perceiving the art of the novel at the time.

One other detail that could seem insignificant is the presence of the flyleaf with no illustrations. Manga artists being paid from the very first page, leaving only the the title on the first page was hard to justify in pther mainstreams magazine, but Garo having an editorial system that left total freedom to its artists allowed Tsuge to be audacious. What seems like total laziness on his part is actually a meticulous choice: the aim was to give to the reader the widest margin of interpretation possible without guiding them with an illustration that would suggest or sum up entirely the theme of his work.

This minor detail acts as a way for him to begin sapping some of the basic foundations of the medium still only limited to entertainment and will use it until the end of his collaboration with Garo.

The next story, Mr Lee’s family is one of his most famous work, parodied many times and even gaining a sequel made by Kuniko Kurita. It’s from this story on that the narrator first appeared as the representation of Yoshiharu Tsuge himself. Along with the next story, Touge no Inu, it shows his fascination with vagrant, beggars and the people living on the edge of society. He took an important inspiration from an essay by literary critic Junzo Karaki depicting these kind of persons.

A view of the seaside was a way for him to finally take a step against the cheap sentimental drama he was forced to draw for rental libraries. As one of the first manga depicting a romance between two adult characters, it truly uses the full extent of the medium by using visual techniques belonging to Gekiga in the literal sense of dramatic pictures. What once only belonged to urban crime stories is now used to present a simple meeting. Wide and silent panels are used to bring about an emotional state instead of the usual dialogue that is here restricted to the minimum, the whole drama is brought by the drawings, his ellipsis and spreads are remarkable. It marks a turning point in his way to introduce his characters.

Red flowers was inspired by one of the first novel from Osamu Dazai : Gyofukuki which tells about the metamorphosis of a young girl into a fish. It's one of the stories that was the most written about. Its publication marks the start of a series of stories with an identical structure in which the author’s avatar meets different people from the countryside. In Incident in the Nijibeta Village a location is clearly defined. In this story, Tsuge learns the basics of fishing with his co-worker S. which is none other than Sanpei Shirato. This one had an important role in Tsuge’s career, not as a teacher but because in 1965, he invited him in a small inn in Shiba which gave him a lot of inspiration as to the location and scenery of his stories. The one that got stuck in the hole of the Izumi river in Nijibeta is also Shirato and this place quickly became an important meeting place for his fans, just as the Chohachi’s inn which continued to subsist in part because of the popularity of this story.

The places featured in his next two stories, Futamata’s valley and Ondoru House are places even more secluded that Tsuge visited in 1967 at a period where national tourism was just beginning to develop. These kind of places have disappeared since then, making these travel logs into valuable testimony about forgotten areas.

Mr Ben’s snow house also presents his characters with sublety while presenting a familial drama. Tsuge has to heart to reward readers that pay attention to every detail as the final panel reveals children toys, telling us a lot about Mr ben’s past.

This anthology allows us to see the progression of an author finally freed from the chains of entertainment after 10 years of hardships drawing stories that didn’t correspond to his vision of art, Garo allowing him to use the full extent of his talent. As varied as these stories can be, be it in their style or settings, it forms a rigorous coherent volume and starts an exhibition of drifting people, exiled from society and creates a dramatic background that will be present in all his works.

By depicting these kinds of people, he gets the whole movement of gekiga richer by getting out of the city, getting rid of its darkness to show these people whose destiny seem to echo a lot more within us in that they are devoid of any spectacular elements.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

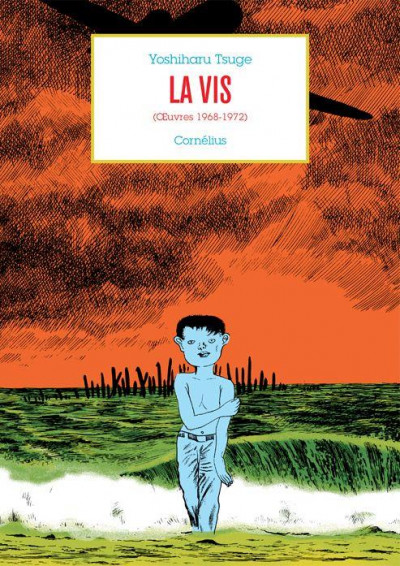

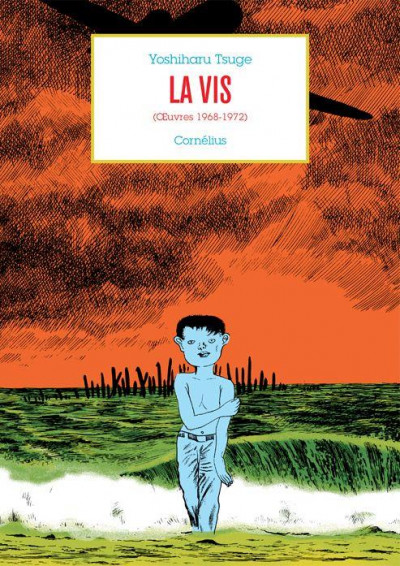

The second anthology is the third one chronologically, going from June 1968 to September 1972

Chapters included are :

Screw-Style (Nejishiki (ねじ式) Garo Zoukangou 1968-06)

Master of the Gensenkan Inn (Gensenkan Shujin (ゲンセンカン主人) Garo 1968-07)

The Morrikiya Girl (Morrikiya no Shojo (もっきり屋の少女) Garo 1968-08)

The Crab (Kani (蟹) Gendai Comic 1970-01)

Master of the Yanagiya Inn (Yanagiya Shunin (やなぎ屋主人) Garo 1970-02)

Dream of a Walk (Yume Yumemiru (夢の散歩)Yagyo#1 1972-04)

Memories of the Summer (Natsu (夏の思いで) Yagyo#2 1972-09)

When the first special issue of Garo came out in June 1968, the magazine was in its golden age. Its subtitle “Junior Magazine” had been gone 2 years prior and a huge part of its readership was made up of college students and working people. Intellectuals and prominent critics were showering it with praise ; Garo was selling like hot cakes.

Popular authors like Sanpei Shirato and Shigeru Mizuki were present in every issue while young talents like Maki Sasaki (Yoku Aru Hanashi) and Seiichi Hayashi (Elegy in Red) were becoming regulars. After receiving negative reviews, Yoshiharu Tsuge’s stories were finally becoming popular, to the point where the first special issue of the magazine was entirely dedicated to him, consisting of previously published stories and a new one that would change everything : Screw-Style

Now considered as one of the most important one-shot of modern manga and one of the most emblematic cultural works of the Japanese 60s, Screw-Style continues to be written about even 50 years after its publication. If his previous stories had different stakes than the traditional “story manga”, this one marks a clear break in this register. Considered as absurd, illogical and beyond understanding, it immediately found its fans among the different bubbling artistic fields of the time. Theater was emancipating with the Juro Kara group and the provocations of Shunji Torayama, while the first protest songs were being released. It’s also the time of independent cinema with the rise of the Art Theater Guild, often considered as the Japanese side of the New Wave. Garo was responsible for the inclusion of comics onto the global cultural sphere and by giving life to his anxieties and fears, Tsuge was able to resonate with people in a climate full of political struggles and an increasing social unease. The novelty of Screw-Style resided more into its completely assumed artistic ambition rather than on the content itself of the story. For the first time, the Art of Comics could rival cinema and literature in its complexity and intricacy.

Then came the first polemics around the deeper meaning of this work. Said to have come from a dream Tsuge had while taking a rooftop nap, some would see in this hallucinated cut-up a meticulous retranscription of a true nightmare.

One month later, Tsuge would say that it didn’t deal with any particular theme and that anybody could interpret is as he wanted, “I simply put together vague dark ideas that I had in mind”. He would also later refute the rumor of this dream and confess that it is lack of time and inspiration that were the cause for the creation of Screw-Style.

Indeed, recent fan discoveries would reveal that most of the iconic panels came straight up from magazine photos but this question of authenticity and creativity didn’t really matter much considering the wide influence it had. Being the first to experiment in a new realm, it would create a small revolution in this field and many would try to replicate this feat.

“I often drew for entertainment but recently I decided to change my way of doing things. Drawing comics has now become private affairs” would he declare soon after its publication.

Master of the Gensenkan Inn published the next month confirms that his stories are still centered around private affairs. His wish to make these worlds believable and tangible is held up by his experience at Mizuki Pro, his drawings having become more detailed and his fascination for old and decrepit places clearly shows itself.

The place and the premise are similar to his previous travel stories, the major difference being that the tone of the story way darker, his positive and humorous style being completely gone. The formal audacity of leaving some speech bubbles empty is still present as well as the exploration of surrealism and horror genres. As if condemned to roam the pits of hell, these characters devoid of any sensibility reflect the mental anguish of the author directly on the reader.

This contrast can also be found in The Morrikiya Girl, a seemingly lighter story. It is the last travel story Tsuge would write for Garo and show for the final time his city-dweller narrator meeting a young girl perfectly similar to the one from The Swamp or Tchiko.

Tsuge shows again his attraction for spontaneous persons living their lives as they see fit without asking themselves too much question.

As in Ondoru House, the narrator’s interest is piqued by the behavior of a local woman and is forced to admit a singular fascination for the habits and customs of a population forgotten by recent urbanization. The relation between the narrator and the young woman Chiyoji is doomed to failure as their different landscapes are hermetical to one another. Instead of starting a new friendship they end up only turning a deaf ears to each other.

After the first 3 stories of this volume, Tsuge puts an end to the thematics he tackled in his Garo period.

In September 1968, he puts to execution one of his fantasy: to vanish without telling anyone and to start a new life from scratch.

Even though this fantasy would turn into failure (he came back to Tokyo 10 days later) his will to vanish and “getting free from a self-conditioned by society” never left him.

Feeling erratic, he stopped writing: the heart wasn't there and he didn't hide it. Indeed, he had just met his wife Maki Fujiwara, comedian in the Juro Kara troup called Jogyo Gekijou. They started living together and Tsuge took his distance with his work, only publishing 2 stories at the beginning of 1970: The Crab and Master of the Yanagiya Inn.

In the first of these two stories, the protagonist also realizes in his way the failure of his life. The suburban life he always dreamed of turns out to be boring and under its humorous tone, he is forced to realize that his dream of isolation was for the most part idealized.

The Crab was ordered for the launch of Gendai Comics and Tsuge would admit that, out of ideas, he decided to write a sequel to Mr. Lee's Family, a story that already had its conclusion.

The month after, Tsuge would come back with Master of the Yanagiya Inn in Garo; published in 2 parts, this story would sign the end of his collaboration with the magazine and was intended as a farewell letter of sort for it.

His confidence and mastery acquired in its columns showed themselves from the shocking and magnificent nude of the first page which would have been impossible to draw a few years prior. The medium had changed and Tsuge with it. His themes of disappearance and voluntary seclusion, a constant in his body of works, are for the first time talked about directly. Its characters are crushed by shadows and applications of black ink tones more than ever before.

The shallows are represented in a crude way without any embellishment and his romantic fascination for outcasts is directly cited with the song Abashiri Bangaichi (song from the movie by the same name directed by Teruo Ishii in 1965 wich popularized the romantic vision of the yakuza and started the career of Ken Takakura). It’s also the first time that his unease is so crudely expressed.

For Yoshiharu Tsuge who perfected himself in the art of evocation and of the unspoken, it marks the end of a cycle.

From then, he would stop writing comics for 2 whole years and instead spend his time traveling, writing and illustrating articles for different magazines, taking advantage of the new tranquility allowed by his royalties: “I don’t draw if I have money. Most of the breaks I took in my career happened when I was financially comfortable”

When Tsuge finally returns to writing comics in 1972, everyone was waiting for him, anticipating his new works. Published in the rather unknown magazine Yagyo, Dream of a Walk took both the public and the critics by surprise. The visual change is radical: minimalist paneling, empty sceneries, white frames and laconic narration…

Tsuge explained the reasons for this major change after his hiatus “I was sick of all this psychologizing jumble of the “Master” series, I wanted to make something lighter with some room to breathe”. With his drawings searching for “a delicate balance between dreams and reality” Tsuge complies his style to the needs of the narration. This story makes him believe in an art of a tale free of justifications and expectations of the readership. Created in a more intentional way than Nejishiki, we can see Yume Yumemiru as his first onirical story.

Memories of the Summer confirms the reinvention of his style. These 2 stories for Yagyo include most of the motifs he will start declining: the break between the main character and his environment, female nudes and sexual aggressions and the thin line between autobiography and fiction.

“After Dram of a Walk, the stories belonging to the style wakakushi manga became more numerous. Readers kept being mistaken and thought I was only faithfully transcribing my travels…but I started longing for this misunderstanding”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

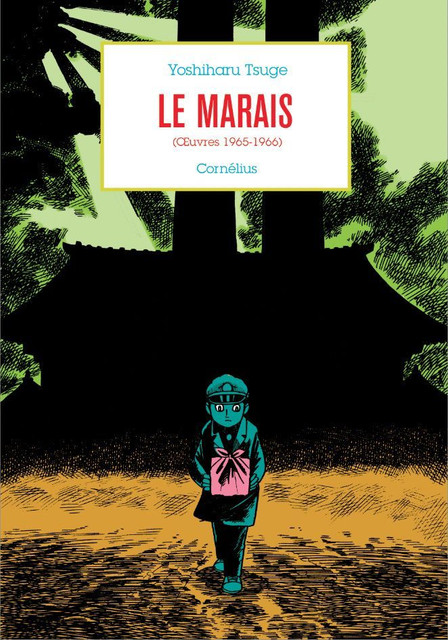

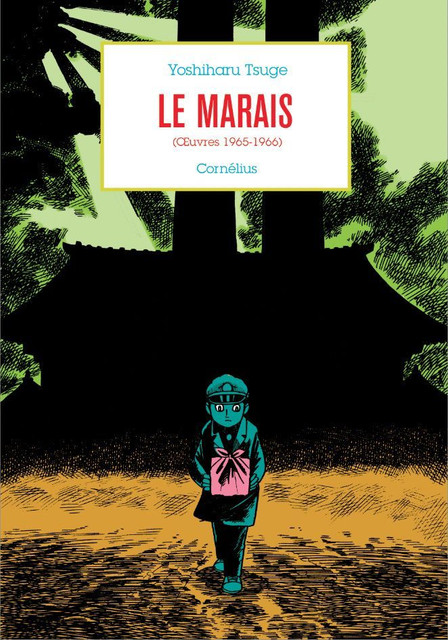

This third volume is the first one of this collection chronologically and contains stories from August 1965 to December 1966 and should be the same as the one in "The Swamp" coming out in a few months.

Chapters included are :

The Rumor (Uwasa no Bushi (噂の武士) Garo 1965-08)

Watermelon Liquor (Suikashu (西瓜酒) Garo 1965-10)

Destiny (Unmei (運命) Garo 1965-12)

The Mysterious Painting (Fushigana e (不思議な絵) Garo 1966-01)

The Swamp (Numa (沼) Garo 1966-02)

Tchiko (Chiko (チーコ) Garo 1966-03)

Mushroom Hunting (Hatsutakegari (初茸がり) Garo 1966-04)

The Librarian's daughter (Garo 1966-09)

The Mysterious Letter (Published in the "Usawa no Bushi" collection 1966-12)

Kunoichi (Published in the "Usawa no Bushi" collection 1966-12)

Handcuffed (Garo 1966-12)

Yoshiharu Tsuge makes his first apparition in Garo with The Rumor a few months after the magazine offered him a potential collaboration. Even though he had 10 years of experience drawing comics prior to that, he had to constantly lived in precarity or in total misery. He then started to draw reluctantly for Yoshihiro Tatsumi's publishing house all while being aware that the network of borrowing libraries where Gekiga was born was doomed to disappear : "The time marking the decline of borrowing libraries was one of the hardest period I lived through. Not only did I have a hard time earning decent wages, I couldn't stand the idea of creating stories for entertainment".

Running out of steam, Tsuge publishes his first story for Garo in August 1965 when he was 28. In it is a very personnal exploitation of the myth of Musashi Miyamoto, all while keeping in line with the graphical style and thematics he had when he drew for borrowing libraries. Musashi steals the spotlight from the narrator in the same way as Mr Lee or the old man in his future creations, already presaging his love for marginalized people.

Watermelon Liquor may be humorous but it once again portrays undernourished characters that can only count on cheap tricks to make their ends meet. In an interview given a few years after his retirement, Tsuge explained that the story would've gained from being more mysterious and that he regrets having kept the final recitative. Rereading the story while ignoring it is probably a good way to understand Tsuge's turmoil at his beginning : " I couldn't be satisfied by endings that resolved everything. Maybe was it then that I started being influenced by literature". If all these narrative ambitions were still but mere unavowed pipe dreams, it would only take a few months for him to finally explore unfamiliar territory with the release of "The Swamp".

But before that, he would release Destiny, proving his skills at recreating classical dramatic structure. This conventionality will not prevent him from showing the roots of some of his later audacity. The relationship of this precarious and unsteady couple is unspired from Tsuge's own situation - this starting point will actually be much more explicit in Tchiko. His romantic relationship results in a suicide attempt and will haunt him until the end of his career. Having a specific historical timeframe allows for a certain distance to be kept and hides its autobiographical core.

In his first stories for Garo, Tsuge tried to deconstruct some of the cliche and to avoid caricature in order to set his characters in a brutal reality, establishing foundations for future works to come. Whatever the type of stories he writes, he cares to go into details about his characters, giving them a bit more depth and subtlety. These details can easily be missed however - like the fact that a man is cleaning the house at the beginning of Destiny suggests that something might be wrong in their couple ; or the fact that the main character of Mysterious Painting is picking up a scroll with his chopsticks shows that he is a second rank samurai and lacks proper etiquette.

His love for marginalized people is also shown by the fact that a lot of his stories are set on riverbanks that are typically reserved for rejects and scums of society. It's also a an echo to his own condition and his aspirations to live far "from this rotten society" like the painter from the Mysterious Painting likes to say. This eccentric painter can be seen as one of the first representations of Tsuge : he liked using his ironic tone when he had to answer questions, especially towards Screw-Style.

Tsuge finishes writing this story in the Autumn of 1965 when he was in an inn in Otaki. Sanpei Shirato, that had already seen his potential, invited Tsuge to stay there with him in order to remotivate him.

"I felt like I was purified. The sky, the mountains, the river, the rain, the inn, going fishing... Every bit of nature was shining of a new light. Birds,insects, stray dogs, rocks... I became aware of forms of life I never even considered until then. The manga I created after that were deeply influenced by the memory of my stay in Otaki."

This experience was decisive. Immersed in the wild for 2 weeks, he developped a taste for travel, found inspiration for new stories as well as a newfound confidence.

Even though the Swamp is said to be the cornerstone of this new type of storytelling, Tsuge was well aware of what he was starting. First story set in contemporary times, the main reaction towards it is that nobody understood it, and even Tatsumi admitted to that.

Tsuge only plays with suggestions and never gives any key to understand his story, the reader can only try and wonder what everything meant. By only showing and not making itself clear, The Swamp insidiously distils a tense atmosphere to disorient the reader and to leave him free to interpret the story as he wants. That's one of the first step towards a rupture with the established codes that Tsuge will reiterate the next month with Chiko.

Tsuge doesn't innovate by writing about his life as an artist without embellishing it, but he is the first to show it without distorting it by the prism of self-mockery.

The fact that the two protagonists live together without being married and that it's the woman who brings the money in is another form of subversion. He also discredits the idea that comics would be by nature funny or entertaining and depicts a bare reality without dramatic elements. Chiko, published in March 1966, is considered today as the first autobiographic manga.

Mushroom Hunting was imagined in his stay in Otaki. Drawn in a more rounded style and close to picture books, it doesn't create uneasiness like the previous stories, but relied more on its instantness than on the complex plots people usually liked.

As mentionned before, the feedbacks were pretty bad and Tsuge will start to work for Mizuki who was overwhelmed with commissions. Having 10 years of experience behind him, he is immediately tasked with drawing characters, sometimes going as far as drawing complete stories. Tsuge won't forget to mention that his ego sufferered a lot from drawing for someone else but still admits that it was a crucial part of his development as an artist :

"What I learned by his side was of inestimable value for the immature man that I was [...] It's at Mizuki Pro that I learned to really take care, to draw into deatails."

If Tsuge stopped publishing any original stories for almost a year, he was still present in the columns of Garo. His next two publications, The Librarian's daughter and Handcuffed were rewritings of old stories he wrote for borrowing libraries.

Handcuffed was redrawn in order to attract the attention of another big magazine, using shamelessly of the most popular codes and inscribing itself in the emblematic hardboiled Gekiga genre ; a flyleaf similar to those by Saul Bass, extended action-scenes, a young hero full of good intentions, gun fights, and a final twist without any happy end.

The Librarian's daughter is important for being a sort of testimony of Tsuge's graphical change when he started working for Mizuki. The scenery feels more detailed and organic, there's more nuance in the shades of black and shadows, the panneling is also improved overall and silent pannels are more numerous making this short more atmospheric.

The same kind of evolution can be seen in The mysterious letter, a crime story he wrote when he was younger and also emblematic of borrowing libraries manga. It was redrawn focusing on 3 layers to fit his anthology book better. This first anthology was edited by Tatsumi's older brother : Shoichi Sakurai. It was composed of 5 stories all present in this volume : The Librarian's daughter, The Rumor, The Mysterious Letter, Watermelon Liquor and Kunoichi.

Kunoichi was first published in 1961 when the popularity of ninja manga was at its peak. Some of Sanpei Shirato trademarks can be observed like the bloody dismemberment, flashy aerian acrobatic feats or silent panels focused on nature to mark the passage of time, the influence of Mizuki characters can also be seen in Sukeza who looks a lot like Kitarou.

Sanpei Shirato would write the postscript for this anthology, dated from March 12th 1966 and it ends like this:

"There are a big number of authors influenced by the works of Yoshiharu Tsuge and I'm one of them. I hope he will continue working hard and become one of these great authors that you can't miss, not only for young artists but for the world of manga as a whole"

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The fourth anthology is also the fourth one chronologically and contains stories going from January 1973 to November 1974

Chapters included are:

The time of the boarding house (Geshuku no Koro (下宿の頃) Young Comic 1973-01)

Ouba's Electroplating Workshop (Ouba Denki Mekki Kougyousho (大場電気鍍金工業所) Bessatsu Manga Story 1973-04)

Nostalgia (Natsukashii Hito (懐かしい ひと) Shuumatsu Kara#2 1973-08)

Realism Inn (Realism no Yado (リアリズムの宿) Manga Story 1973-11)

Incident (Jiken (事件) Yagyou #5 1974-04)

Inn of the Withered Field (Kureno no Yado (枯野の宿) Manga Story 1974-07)

Yoshio's Youth (Yoshio no Seishun (義男の青春) Manga Sunday 1974-11-09 to 1974-11-23)

Since the publication of Screw-Style, Yoshiharu Tsuge draws less : this unexpected success earns him his first royalties and his work as assistant to Shigeru Mizuku allowed him to have stable income but working for someone else was a pain for him so he quit this job in 1972 after 6 years. As he was waiting for some new orders, he got contacted by the popular magazine Young Comics.

Yoshiharu Tsuge is starting to discover the world of mainstream weekly magazines

but having spent 10 years into making the same kind of entertaining works for borrowing libraries, he's aware that the readership has different expectations to those from

a niche magazine like Yagyo.

"I didn't have any trouble writing The Time of the Boarding House. I used a basis a pure entertainment and added erotism on top of it, nothing more"

He chose to use his early days working for Wakagi Shobou alongside Shinji Nagashima and Masaharu Endou, the latter being used as an inspiration for the friend of the main character. This first order from Young Comics is overall more carefree than usual.

Tsuge will go one to create Ouba's Electroplating Workshop for Bessatsu Manga Story. The lighter tone is replaced with a harsher reality: "This is the first time where I felt like I was actually writing about me"

That's because he made use of his childhood rumories, depicting the daily hardships of the people in this workshop. The setting is very precise and documentary-like and a lot of time was spent in giving life to the characters.

"Only accumulating the small details by increasing the number of accessories is not enough to have a satisfying result. The details that I'm talking about are not to be found directly in the quality of my drawings but by the gestures and the things that no one ever pays attenton to. It's not enough to add them as it is with the goal to create an effect, they have to be integrated into the structure of the story"

The apparition of Miyoshi walking on his hands and mentionning the pilot formation school is there to suggest both the admiration of Yoshio and frame an historical context.

The name of the workshop will be changed at the last minute to be coherent with a story from his brother Tadao Tsuge called Shouwa Goeika (昭和御詠歌 Garo 1969-04) that also focuse on the hardships that their family went through. These two stories are a unique testimony to the life in the rough areas in the very end of the War.

This return to mainstream magazines will turn out to be very short as his next order comes from Shuumatsu Kara, a literary magazine that hosted old writers of Garo like Akasegawa Genpei or Sasaki Maki. This is another proof that manga has really become legitimate among the global cultural scene.

The couple featured in Nostalgia is the same a the one from Memories of the Summer that is meant to personify Yoshiharu Tsuge and his wife Maki Fujiwara. The dialogue and the play on the gazes like the fact the narrator is always turning his back his wife shows a resigned vision of the couple. His distance with his first love, the inaccessible Yaeko is made clear by using a realist style as soon as he enters the bath. The narrator is trapped into an idealized past and is ready to give up on everything to find it back. The violence of the attempted rape is increased by the calm tone of the story.

Realism Inn is also about finding back an idealized past embodies by Japan's Back Coast that wasn't part of the modernization of the country. The detailed backgrounds and the heavy shadows present in his last stories for Garo are back again. It's also another one of his travel stories at the exception that this time his commercial intent of traveling to find inspiration for his stories is made explicit rather than being a pretext to escape his melancholia. There's also no chance that anyone would want to spend a night in the inn depicted here: "I like to spend time in peddler's inn but it's important to know that there's no good inn of this kind"

Peddler's inn were already disappearing around this time and his portrayal of it is similar to the one in Youji Yamada's movie series Otoko wa Tsurai yo.

The parallel made between The Spider's Thread and the narrator who hoped to use people's misery for his own gain without facing any consequences is a way for Tsuge to show that he doesn't aspire for more fame or money.

Back in the magazine Yagyou with Incident, this story show a strong bond between the two main protagonists that are united against the outside world. Their isolation is shown by never putting them in the same pannels as the other characters. 20 years later, Tsuge will relate the stormy relationships he had in the neighborhoods he lived in:

"As of today, I am still repulsed by society because it tries to exclude everything that is different or eccentric. The more people lack independance and individuality, the more they will try to fit fantasized social norms and persecute and ostracize those that are outside this group"

Similarly to A view of the seaside, Inn of the Withered Field gives a huge importance to the scenery and tries to imitate Edo-era etchings. Tsuge uses the early Hakaba Kitarou comics for the appearance of his main character and once again shows his love for spontaneous persons living their lives as they see fit without asking themselves too much question in the character of Iwao. A parallel is drawn between the lives of these two: one is a comic writer who dreams of living in the countryside while the other lives in the countryside and dreams of becoming a comics artist. Their growing frienship is interrupted by the apparition of the pragmatic wife who is here to hold up the whims of her husband, a regular motif in Tsuge's bibliography.

Yoshio's Youth was drawn at the same time as Inn of the Withered Field without any magazines in mind. This long story is refused everywhere and Tsuge comes to the realization that being praised by influencial intellectuals doesn't necessarily means getting all powers as a mangaka. He's 37 and it's the final straw: "I felt like the world of manga wasn't the same and I was ready to change career for real"

He will move out and open a coffee shop in front of the Ogikubo train station but gives up after 2 months because it ends up being too complicated. Yoshio's Youth will finally be accepted in Manga Sunday and be published in 3-part.

This story tells about his early days as an artist and he mentions the joy he had taking his inspiration from Kouji Uno's writing style:

"I found in his novels and unexpected charm that I hadn't felt in anything I had read before that. Everything is so carefree and Kouji Uno spends a lot of time writing details about unimporant things. I tried to find back this way of writing slowly and this old-fashioned but refreshing style with my story. Everything that happens in Yoshio's Youth is based on personal experiences"

Tsuge's describes his meeting with Akira Okada, his first mentor, with who he will learn about coffee, classical music and the joys of public baths.

It's one of the rare cases where Tsuge draws spontaneously, with a geniune will to draw but the lack of positive reception will break this short spurt of enthusiasm and the last few pages implying that the whole thing was about his loss of innocence before struggling to be successful are also a premonition of the most troublesome times Yoshiharu Tsuge will go through after that...

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

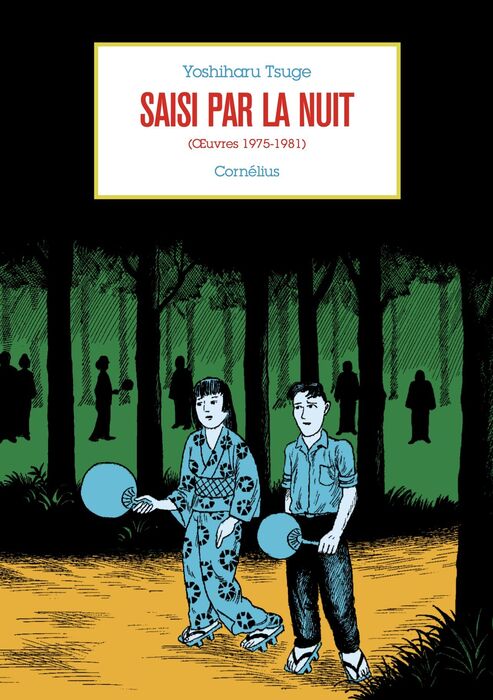

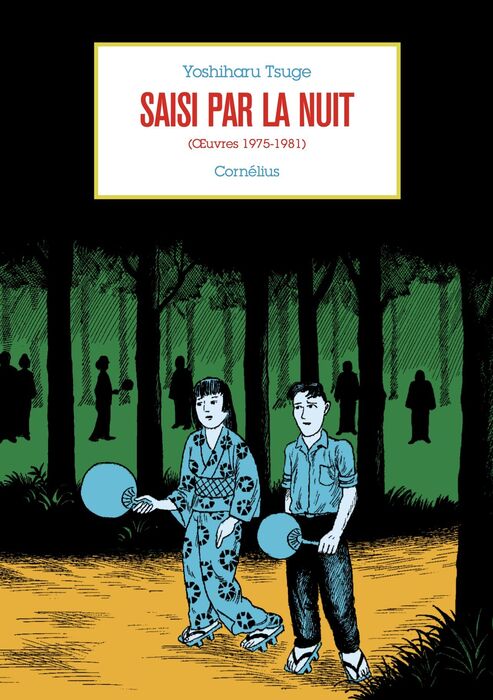

The fifth anthology is also the fifth one chronologically and contains stories going from April 1975 to January 1981

Chapters included are:

Commoner's Inn (Shomin Onjuku (庶民御宿) Manga Sunday 1975-04)

A Room for Boredom (Taikutsuna Heya (退屈な部屋) Manga Sunday 1975-10)

Caught by the Night (Yoru ga Tsukamu (夜が掴む) Manga Sunday 1976-09)

Part-time Job (Arubaito (アルバイト) Poem 1977-01)

Life at Cape Komatsu (Komatsu Misaki no Seikatsu (コマツ岬の生活) Yagyou #7 1978-06)

The Deadly Dried Squid Technique (Hissatsu Surume Katame (必殺するめ固め) Custom Comic 1979-07)

Outside Inflation (Soto no Fukurami (外のふくらみ) Yagyou#8 1979-05)

Yoshibo's Crime (Yoshibou no Hanzai (ヨシボーの犯罪) Custom Comic 1979-09)

The Fish Stone (Sakana Seki (魚石) Big Gold #4 1979-11)

Hands at the Window (Mado no Te (窓の手) Custom Comic 1980-03

Aizu Fishing Inn (Aizu no Tsuri Yado (会津の釣り宿) Custom Comic 1980-05)

Playful Days (Nichi no Tawamure (日の戯れ) Custom Comic 1981-01)

Yoshiharu Tsuge repeated it all throughout his career, for him creation is more of a constraint than a necessity: "If only I could live without having to draw, but alas, I need money in order to live; and to draw again when I run out of money". The man who gained fame in 1968 with "Screw-style" slows considerably his publication rate from the 70s onwards. The royalties coming since he left Garo are constant and allow him to publish stories only once in a while. Severe personnal problems will force him to slow down his rythm even more in the second half of the 70s. Going through a midlife crisis, inspiration doesn't come as easily and he has to reuse the formulas that made hime famous: travel logs, tales from everyday life and onirical stories, without rehashing them despite his chaotic emotionnal state, he still pursues a form of authenticity.

Published in Manga Sunday in April 1975, "Commoner's Inn" signs the return of his travel logs with the main difference being that its main character is for the first time accompanied by a sidekick and brings back the comical dynamic of "Time of the boarding house" to make his story progress. The sex scene he drew to appeal to the readers is longer than usual. Proud of this result, he mentions in an interview that the secret to a well made drawing is to thrill the imagination.

"A room for boredom" is the last story to showcase the couple from "Incident". Once again, his desire to escape are hindered by his wife who represents for him everything he tries to escape: his mother.

-In writing

Other Links:

Instagram - Ryan Holmberg on Maki Fujiwara's picture diary

Youtube - Interview of Ryan Holmberg on The Swamp

Gallery from the Angoulême exposition on Tsuge

For those who would need a bit more informations, Yoshiharu Tsuge is one of the most important authors of Garo magazine along with Yoshihiro Tatsumi and Sanpei Shirato.

He is the creator of a new and avant-guarde genre called watakushi manga or comics of the self where autobiography and fiction blend together in order to create a new form of authenticity. He is also characterized by a reject of entertainment constraints in favor of adult stories breaking off from classical narrative structure in particular with how his stories end abruptly and don’t necessarily resolve the conflict at hand.

We could imagine it took so long for him to accept being published in foreign countries because of how personal his stories were, he mentions in an interview :

You wonder why it took so long?… It’s hard to explain… For a long time I tried to escape other people’s attention. I’ve never liked to be put under the spotlight. I only wanted to lead a quiet life. In Japan we say ite inai, which means living on the margins, not really being engaged with society, trying to be almost invisible if you like.

Cornelius (the French editor) first published anthology should be the second one chronologically,

going from march 1967 to June 1968, which basically is the time where his style became more refined after meeting a critical failure and taking a year off to work as an assistant to Shigeru Mizuki. Entitled “Les fleurs rouges” it regroups different stories from Akai hana and Neji-shiki

Chapters included are :

The Wake (Tsuya (通夜) Garo 1967-03)

In Full Sun ( Bessatsu Shonen King 1967-04)

Salamander (Sanshouuo (山椒魚) Garo 1967-05)

Mr. Lee’s Family (Ri-san Ikka (李さん一家) Garo 1967-06)

The Dog of the Mountain Pass (Touge no Inu (峠の犬) Garo 1967-08)

A View of the Seaside (Umibe no Jokei (海辺の叙景) Garo 1967-09)

Red Flowers (Akai Hana (紅い花) Garo 1967-10)

Incident in the Nijibeta Village (Nijibetamura Jiken (西部田村事件) Garo 1967-12)

Chouhashi’s Inn (Chouhachi no Yado (長八の宿) Garo 1968-01)

Futamata’s Valley (Futamata Keikoku (二岐渓谷) Garo 1968-02)

Ondoru House (Ondoru Koya (オンドル小屋) Garo 1968-04)

Mr. Ben’s Snow House (Honyaradou no Ben-san (ほんやら洞のべんさん) Garo 1968-06)

The first chapter The wake is a real rebirth in his career as he acquired more advanced technical abilities when working with Mizuki which allowed him to give life to his visual ambitions, as well as financial stability that allowed him to refuse orders from other magazines and focus entirely on Garo.

He still accepted a final collaboration with Bessatsu Shonen King where he redrew a story created 7 year before. The scenery and characters are a lot more detailed than his forst story published in Garo : as much as Tsuge is known for never having assistants to help him, he asked for the help of Ryoichi Ikegami for this particular story.

This rebirth continues with the Salamander loosely based on the short story by the same name created by Masuji Ibuse (can be read here) . Barely 10 pages long, it perpetuates the genre of dark comedy that started with the wake, it can be noted that it shares similarities with some of Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s stories, most notably with the presence of a dead foetus. It’s from this point that Tsuge starts using internal monologues to characterize the narrator. This subtle change to the first person narration is important enough to be noted when many gives him credit to be the father of autobiographical manga – this change can be compared to the inclusion of direct narration in Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield which created a rupture in the way of perceiving the art of the novel at the time.

One other detail that could seem insignificant is the presence of the flyleaf with no illustrations. Manga artists being paid from the very first page, leaving only the the title on the first page was hard to justify in pther mainstreams magazine, but Garo having an editorial system that left total freedom to its artists allowed Tsuge to be audacious. What seems like total laziness on his part is actually a meticulous choice: the aim was to give to the reader the widest margin of interpretation possible without guiding them with an illustration that would suggest or sum up entirely the theme of his work.

This minor detail acts as a way for him to begin sapping some of the basic foundations of the medium still only limited to entertainment and will use it until the end of his collaboration with Garo.

The next story, Mr Lee’s family is one of his most famous work, parodied many times and even gaining a sequel made by Kuniko Kurita. It’s from this story on that the narrator first appeared as the representation of Yoshiharu Tsuge himself. Along with the next story, Touge no Inu, it shows his fascination with vagrant, beggars and the people living on the edge of society. He took an important inspiration from an essay by literary critic Junzo Karaki depicting these kind of persons.

A view of the seaside was a way for him to finally take a step against the cheap sentimental drama he was forced to draw for rental libraries. As one of the first manga depicting a romance between two adult characters, it truly uses the full extent of the medium by using visual techniques belonging to Gekiga in the literal sense of dramatic pictures. What once only belonged to urban crime stories is now used to present a simple meeting. Wide and silent panels are used to bring about an emotional state instead of the usual dialogue that is here restricted to the minimum, the whole drama is brought by the drawings, his ellipsis and spreads are remarkable. It marks a turning point in his way to introduce his characters.

Red flowers was inspired by one of the first novel from Osamu Dazai : Gyofukuki which tells about the metamorphosis of a young girl into a fish. It's one of the stories that was the most written about. Its publication marks the start of a series of stories with an identical structure in which the author’s avatar meets different people from the countryside. In Incident in the Nijibeta Village a location is clearly defined. In this story, Tsuge learns the basics of fishing with his co-worker S. which is none other than Sanpei Shirato. This one had an important role in Tsuge’s career, not as a teacher but because in 1965, he invited him in a small inn in Shiba which gave him a lot of inspiration as to the location and scenery of his stories. The one that got stuck in the hole of the Izumi river in Nijibeta is also Shirato and this place quickly became an important meeting place for his fans, just as the Chohachi’s inn which continued to subsist in part because of the popularity of this story.

The places featured in his next two stories, Futamata’s valley and Ondoru House are places even more secluded that Tsuge visited in 1967 at a period where national tourism was just beginning to develop. These kind of places have disappeared since then, making these travel logs into valuable testimony about forgotten areas.

Mr Ben’s snow house also presents his characters with sublety while presenting a familial drama. Tsuge has to heart to reward readers that pay attention to every detail as the final panel reveals children toys, telling us a lot about Mr ben’s past.

This anthology allows us to see the progression of an author finally freed from the chains of entertainment after 10 years of hardships drawing stories that didn’t correspond to his vision of art, Garo allowing him to use the full extent of his talent. As varied as these stories can be, be it in their style or settings, it forms a rigorous coherent volume and starts an exhibition of drifting people, exiled from society and creates a dramatic background that will be present in all his works.

By depicting these kinds of people, he gets the whole movement of gekiga richer by getting out of the city, getting rid of its darkness to show these people whose destiny seem to echo a lot more within us in that they are devoid of any spectacular elements.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The second anthology is the third one chronologically, going from June 1968 to September 1972

Chapters included are :

Screw-Style (Nejishiki (ねじ式) Garo Zoukangou 1968-06)

Master of the Gensenkan Inn (Gensenkan Shujin (ゲンセンカン主人) Garo 1968-07)

The Morrikiya Girl (Morrikiya no Shojo (もっきり屋の少女) Garo 1968-08)

The Crab (Kani (蟹) Gendai Comic 1970-01)

Master of the Yanagiya Inn (Yanagiya Shunin (やなぎ屋主人) Garo 1970-02)

Dream of a Walk (Yume Yumemiru (夢の散歩)Yagyo#1 1972-04)

Memories of the Summer (Natsu (夏の思いで) Yagyo#2 1972-09)

When the first special issue of Garo came out in June 1968, the magazine was in its golden age. Its subtitle “Junior Magazine” had been gone 2 years prior and a huge part of its readership was made up of college students and working people. Intellectuals and prominent critics were showering it with praise ; Garo was selling like hot cakes.

Popular authors like Sanpei Shirato and Shigeru Mizuki were present in every issue while young talents like Maki Sasaki (Yoku Aru Hanashi) and Seiichi Hayashi (Elegy in Red) were becoming regulars. After receiving negative reviews, Yoshiharu Tsuge’s stories were finally becoming popular, to the point where the first special issue of the magazine was entirely dedicated to him, consisting of previously published stories and a new one that would change everything : Screw-Style

Now considered as one of the most important one-shot of modern manga and one of the most emblematic cultural works of the Japanese 60s, Screw-Style continues to be written about even 50 years after its publication. If his previous stories had different stakes than the traditional “story manga”, this one marks a clear break in this register. Considered as absurd, illogical and beyond understanding, it immediately found its fans among the different bubbling artistic fields of the time. Theater was emancipating with the Juro Kara group and the provocations of Shunji Torayama, while the first protest songs were being released. It’s also the time of independent cinema with the rise of the Art Theater Guild, often considered as the Japanese side of the New Wave. Garo was responsible for the inclusion of comics onto the global cultural sphere and by giving life to his anxieties and fears, Tsuge was able to resonate with people in a climate full of political struggles and an increasing social unease. The novelty of Screw-Style resided more into its completely assumed artistic ambition rather than on the content itself of the story. For the first time, the Art of Comics could rival cinema and literature in its complexity and intricacy.

Then came the first polemics around the deeper meaning of this work. Said to have come from a dream Tsuge had while taking a rooftop nap, some would see in this hallucinated cut-up a meticulous retranscription of a true nightmare.

One month later, Tsuge would say that it didn’t deal with any particular theme and that anybody could interpret is as he wanted, “I simply put together vague dark ideas that I had in mind”. He would also later refute the rumor of this dream and confess that it is lack of time and inspiration that were the cause for the creation of Screw-Style.

Indeed, recent fan discoveries would reveal that most of the iconic panels came straight up from magazine photos but this question of authenticity and creativity didn’t really matter much considering the wide influence it had. Being the first to experiment in a new realm, it would create a small revolution in this field and many would try to replicate this feat.

“I often drew for entertainment but recently I decided to change my way of doing things. Drawing comics has now become private affairs” would he declare soon after its publication.

Master of the Gensenkan Inn published the next month confirms that his stories are still centered around private affairs. His wish to make these worlds believable and tangible is held up by his experience at Mizuki Pro, his drawings having become more detailed and his fascination for old and decrepit places clearly shows itself.

The place and the premise are similar to his previous travel stories, the major difference being that the tone of the story way darker, his positive and humorous style being completely gone. The formal audacity of leaving some speech bubbles empty is still present as well as the exploration of surrealism and horror genres. As if condemned to roam the pits of hell, these characters devoid of any sensibility reflect the mental anguish of the author directly on the reader.

This contrast can also be found in The Morrikiya Girl, a seemingly lighter story. It is the last travel story Tsuge would write for Garo and show for the final time his city-dweller narrator meeting a young girl perfectly similar to the one from The Swamp or Tchiko.

Tsuge shows again his attraction for spontaneous persons living their lives as they see fit without asking themselves too much question.

As in Ondoru House, the narrator’s interest is piqued by the behavior of a local woman and is forced to admit a singular fascination for the habits and customs of a population forgotten by recent urbanization. The relation between the narrator and the young woman Chiyoji is doomed to failure as their different landscapes are hermetical to one another. Instead of starting a new friendship they end up only turning a deaf ears to each other.

After the first 3 stories of this volume, Tsuge puts an end to the thematics he tackled in his Garo period.

In September 1968, he puts to execution one of his fantasy: to vanish without telling anyone and to start a new life from scratch.

Even though this fantasy would turn into failure (he came back to Tokyo 10 days later) his will to vanish and “getting free from a self-conditioned by society” never left him.

Feeling erratic, he stopped writing: the heart wasn't there and he didn't hide it. Indeed, he had just met his wife Maki Fujiwara, comedian in the Juro Kara troup called Jogyo Gekijou. They started living together and Tsuge took his distance with his work, only publishing 2 stories at the beginning of 1970: The Crab and Master of the Yanagiya Inn.

In the first of these two stories, the protagonist also realizes in his way the failure of his life. The suburban life he always dreamed of turns out to be boring and under its humorous tone, he is forced to realize that his dream of isolation was for the most part idealized.

The Crab was ordered for the launch of Gendai Comics and Tsuge would admit that, out of ideas, he decided to write a sequel to Mr. Lee's Family, a story that already had its conclusion.

The month after, Tsuge would come back with Master of the Yanagiya Inn in Garo; published in 2 parts, this story would sign the end of his collaboration with the magazine and was intended as a farewell letter of sort for it.

His confidence and mastery acquired in its columns showed themselves from the shocking and magnificent nude of the first page which would have been impossible to draw a few years prior. The medium had changed and Tsuge with it. His themes of disappearance and voluntary seclusion, a constant in his body of works, are for the first time talked about directly. Its characters are crushed by shadows and applications of black ink tones more than ever before.

The shallows are represented in a crude way without any embellishment and his romantic fascination for outcasts is directly cited with the song Abashiri Bangaichi (song from the movie by the same name directed by Teruo Ishii in 1965 wich popularized the romantic vision of the yakuza and started the career of Ken Takakura). It’s also the first time that his unease is so crudely expressed.

For Yoshiharu Tsuge who perfected himself in the art of evocation and of the unspoken, it marks the end of a cycle.

From then, he would stop writing comics for 2 whole years and instead spend his time traveling, writing and illustrating articles for different magazines, taking advantage of the new tranquility allowed by his royalties: “I don’t draw if I have money. Most of the breaks I took in my career happened when I was financially comfortable”

When Tsuge finally returns to writing comics in 1972, everyone was waiting for him, anticipating his new works. Published in the rather unknown magazine Yagyo, Dream of a Walk took both the public and the critics by surprise. The visual change is radical: minimalist paneling, empty sceneries, white frames and laconic narration…

Tsuge explained the reasons for this major change after his hiatus “I was sick of all this psychologizing jumble of the “Master” series, I wanted to make something lighter with some room to breathe”. With his drawings searching for “a delicate balance between dreams and reality” Tsuge complies his style to the needs of the narration. This story makes him believe in an art of a tale free of justifications and expectations of the readership. Created in a more intentional way than Nejishiki, we can see Yume Yumemiru as his first onirical story.

Memories of the Summer confirms the reinvention of his style. These 2 stories for Yagyo include most of the motifs he will start declining: the break between the main character and his environment, female nudes and sexual aggressions and the thin line between autobiography and fiction.

“After Dram of a Walk, the stories belonging to the style wakakushi manga became more numerous. Readers kept being mistaken and thought I was only faithfully transcribing my travels…but I started longing for this misunderstanding”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This third volume is the first one of this collection chronologically and contains stories from August 1965 to December 1966 and should be the same as the one in "The Swamp" coming out in a few months.

Chapters included are :

The Rumor (Uwasa no Bushi (噂の武士) Garo 1965-08)

Watermelon Liquor (Suikashu (西瓜酒) Garo 1965-10)

Destiny (Unmei (運命) Garo 1965-12)

The Mysterious Painting (Fushigana e (不思議な絵) Garo 1966-01)

The Swamp (Numa (沼) Garo 1966-02)

Tchiko (Chiko (チーコ) Garo 1966-03)

Mushroom Hunting (Hatsutakegari (初茸がり) Garo 1966-04)

The Librarian's daughter (Garo 1966-09)

The Mysterious Letter (Published in the "Usawa no Bushi" collection 1966-12)

Kunoichi (Published in the "Usawa no Bushi" collection 1966-12)

Handcuffed (Garo 1966-12)

Yoshiharu Tsuge makes his first apparition in Garo with The Rumor a few months after the magazine offered him a potential collaboration. Even though he had 10 years of experience drawing comics prior to that, he had to constantly lived in precarity or in total misery. He then started to draw reluctantly for Yoshihiro Tatsumi's publishing house all while being aware that the network of borrowing libraries where Gekiga was born was doomed to disappear : "The time marking the decline of borrowing libraries was one of the hardest period I lived through. Not only did I have a hard time earning decent wages, I couldn't stand the idea of creating stories for entertainment".

Running out of steam, Tsuge publishes his first story for Garo in August 1965 when he was 28. In it is a very personnal exploitation of the myth of Musashi Miyamoto, all while keeping in line with the graphical style and thematics he had when he drew for borrowing libraries. Musashi steals the spotlight from the narrator in the same way as Mr Lee or the old man in his future creations, already presaging his love for marginalized people.

Watermelon Liquor may be humorous but it once again portrays undernourished characters that can only count on cheap tricks to make their ends meet. In an interview given a few years after his retirement, Tsuge explained that the story would've gained from being more mysterious and that he regrets having kept the final recitative. Rereading the story while ignoring it is probably a good way to understand Tsuge's turmoil at his beginning : " I couldn't be satisfied by endings that resolved everything. Maybe was it then that I started being influenced by literature". If all these narrative ambitions were still but mere unavowed pipe dreams, it would only take a few months for him to finally explore unfamiliar territory with the release of "The Swamp".

But before that, he would release Destiny, proving his skills at recreating classical dramatic structure. This conventionality will not prevent him from showing the roots of some of his later audacity. The relationship of this precarious and unsteady couple is unspired from Tsuge's own situation - this starting point will actually be much more explicit in Tchiko. His romantic relationship results in a suicide attempt and will haunt him until the end of his career. Having a specific historical timeframe allows for a certain distance to be kept and hides its autobiographical core.

In his first stories for Garo, Tsuge tried to deconstruct some of the cliche and to avoid caricature in order to set his characters in a brutal reality, establishing foundations for future works to come. Whatever the type of stories he writes, he cares to go into details about his characters, giving them a bit more depth and subtlety. These details can easily be missed however - like the fact that a man is cleaning the house at the beginning of Destiny suggests that something might be wrong in their couple ; or the fact that the main character of Mysterious Painting is picking up a scroll with his chopsticks shows that he is a second rank samurai and lacks proper etiquette.

His love for marginalized people is also shown by the fact that a lot of his stories are set on riverbanks that are typically reserved for rejects and scums of society. It's also a an echo to his own condition and his aspirations to live far "from this rotten society" like the painter from the Mysterious Painting likes to say. This eccentric painter can be seen as one of the first representations of Tsuge : he liked using his ironic tone when he had to answer questions, especially towards Screw-Style.

Tsuge finishes writing this story in the Autumn of 1965 when he was in an inn in Otaki. Sanpei Shirato, that had already seen his potential, invited Tsuge to stay there with him in order to remotivate him.

"I felt like I was purified. The sky, the mountains, the river, the rain, the inn, going fishing... Every bit of nature was shining of a new light. Birds,insects, stray dogs, rocks... I became aware of forms of life I never even considered until then. The manga I created after that were deeply influenced by the memory of my stay in Otaki."

This experience was decisive. Immersed in the wild for 2 weeks, he developped a taste for travel, found inspiration for new stories as well as a newfound confidence.

Even though the Swamp is said to be the cornerstone of this new type of storytelling, Tsuge was well aware of what he was starting. First story set in contemporary times, the main reaction towards it is that nobody understood it, and even Tatsumi admitted to that.

Tsuge only plays with suggestions and never gives any key to understand his story, the reader can only try and wonder what everything meant. By only showing and not making itself clear, The Swamp insidiously distils a tense atmosphere to disorient the reader and to leave him free to interpret the story as he wants. That's one of the first step towards a rupture with the established codes that Tsuge will reiterate the next month with Chiko.

Tsuge doesn't innovate by writing about his life as an artist without embellishing it, but he is the first to show it without distorting it by the prism of self-mockery.

The fact that the two protagonists live together without being married and that it's the woman who brings the money in is another form of subversion. He also discredits the idea that comics would be by nature funny or entertaining and depicts a bare reality without dramatic elements. Chiko, published in March 1966, is considered today as the first autobiographic manga.

Mushroom Hunting was imagined in his stay in Otaki. Drawn in a more rounded style and close to picture books, it doesn't create uneasiness like the previous stories, but relied more on its instantness than on the complex plots people usually liked.

As mentionned before, the feedbacks were pretty bad and Tsuge will start to work for Mizuki who was overwhelmed with commissions. Having 10 years of experience behind him, he is immediately tasked with drawing characters, sometimes going as far as drawing complete stories. Tsuge won't forget to mention that his ego sufferered a lot from drawing for someone else but still admits that it was a crucial part of his development as an artist :

"What I learned by his side was of inestimable value for the immature man that I was [...] It's at Mizuki Pro that I learned to really take care, to draw into deatails."

If Tsuge stopped publishing any original stories for almost a year, he was still present in the columns of Garo. His next two publications, The Librarian's daughter and Handcuffed were rewritings of old stories he wrote for borrowing libraries.

Handcuffed was redrawn in order to attract the attention of another big magazine, using shamelessly of the most popular codes and inscribing itself in the emblematic hardboiled Gekiga genre ; a flyleaf similar to those by Saul Bass, extended action-scenes, a young hero full of good intentions, gun fights, and a final twist without any happy end.

The Librarian's daughter is important for being a sort of testimony of Tsuge's graphical change when he started working for Mizuki. The scenery feels more detailed and organic, there's more nuance in the shades of black and shadows, the panneling is also improved overall and silent pannels are more numerous making this short more atmospheric.

The same kind of evolution can be seen in The mysterious letter, a crime story he wrote when he was younger and also emblematic of borrowing libraries manga. It was redrawn focusing on 3 layers to fit his anthology book better. This first anthology was edited by Tatsumi's older brother : Shoichi Sakurai. It was composed of 5 stories all present in this volume : The Librarian's daughter, The Rumor, The Mysterious Letter, Watermelon Liquor and Kunoichi.

Kunoichi was first published in 1961 when the popularity of ninja manga was at its peak. Some of Sanpei Shirato trademarks can be observed like the bloody dismemberment, flashy aerian acrobatic feats or silent panels focused on nature to mark the passage of time, the influence of Mizuki characters can also be seen in Sukeza who looks a lot like Kitarou.

Sanpei Shirato would write the postscript for this anthology, dated from March 12th 1966 and it ends like this:

"There are a big number of authors influenced by the works of Yoshiharu Tsuge and I'm one of them. I hope he will continue working hard and become one of these great authors that you can't miss, not only for young artists but for the world of manga as a whole"

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The fourth anthology is also the fourth one chronologically and contains stories going from January 1973 to November 1974

Chapters included are:

The time of the boarding house (Geshuku no Koro (下宿の頃) Young Comic 1973-01)

Ouba's Electroplating Workshop (Ouba Denki Mekki Kougyousho (大場電気鍍金工業所) Bessatsu Manga Story 1973-04)

Nostalgia (Natsukashii Hito (懐かしい ひと) Shuumatsu Kara#2 1973-08)

Realism Inn (Realism no Yado (リアリズムの宿) Manga Story 1973-11)

Incident (Jiken (事件) Yagyou #5 1974-04)

Inn of the Withered Field (Kureno no Yado (枯野の宿) Manga Story 1974-07)

Yoshio's Youth (Yoshio no Seishun (義男の青春) Manga Sunday 1974-11-09 to 1974-11-23)

Since the publication of Screw-Style, Yoshiharu Tsuge draws less : this unexpected success earns him his first royalties and his work as assistant to Shigeru Mizuku allowed him to have stable income but working for someone else was a pain for him so he quit this job in 1972 after 6 years. As he was waiting for some new orders, he got contacted by the popular magazine Young Comics.

Yoshiharu Tsuge is starting to discover the world of mainstream weekly magazines

but having spent 10 years into making the same kind of entertaining works for borrowing libraries, he's aware that the readership has different expectations to those from

a niche magazine like Yagyo.

"I didn't have any trouble writing The Time of the Boarding House. I used a basis a pure entertainment and added erotism on top of it, nothing more"

He chose to use his early days working for Wakagi Shobou alongside Shinji Nagashima and Masaharu Endou, the latter being used as an inspiration for the friend of the main character. This first order from Young Comics is overall more carefree than usual.

Tsuge will go one to create Ouba's Electroplating Workshop for Bessatsu Manga Story. The lighter tone is replaced with a harsher reality: "This is the first time where I felt like I was actually writing about me"

That's because he made use of his childhood rumories, depicting the daily hardships of the people in this workshop. The setting is very precise and documentary-like and a lot of time was spent in giving life to the characters.

"Only accumulating the small details by increasing the number of accessories is not enough to have a satisfying result. The details that I'm talking about are not to be found directly in the quality of my drawings but by the gestures and the things that no one ever pays attenton to. It's not enough to add them as it is with the goal to create an effect, they have to be integrated into the structure of the story"

The apparition of Miyoshi walking on his hands and mentionning the pilot formation school is there to suggest both the admiration of Yoshio and frame an historical context.

The name of the workshop will be changed at the last minute to be coherent with a story from his brother Tadao Tsuge called Shouwa Goeika (昭和御詠歌 Garo 1969-04) that also focuse on the hardships that their family went through. These two stories are a unique testimony to the life in the rough areas in the very end of the War.

This return to mainstream magazines will turn out to be very short as his next order comes from Shuumatsu Kara, a literary magazine that hosted old writers of Garo like Akasegawa Genpei or Sasaki Maki. This is another proof that manga has really become legitimate among the global cultural scene.

The couple featured in Nostalgia is the same a the one from Memories of the Summer that is meant to personify Yoshiharu Tsuge and his wife Maki Fujiwara. The dialogue and the play on the gazes like the fact the narrator is always turning his back his wife shows a resigned vision of the couple. His distance with his first love, the inaccessible Yaeko is made clear by using a realist style as soon as he enters the bath. The narrator is trapped into an idealized past and is ready to give up on everything to find it back. The violence of the attempted rape is increased by the calm tone of the story.

Realism Inn is also about finding back an idealized past embodies by Japan's Back Coast that wasn't part of the modernization of the country. The detailed backgrounds and the heavy shadows present in his last stories for Garo are back again. It's also another one of his travel stories at the exception that this time his commercial intent of traveling to find inspiration for his stories is made explicit rather than being a pretext to escape his melancholia. There's also no chance that anyone would want to spend a night in the inn depicted here: "I like to spend time in peddler's inn but it's important to know that there's no good inn of this kind"

Peddler's inn were already disappearing around this time and his portrayal of it is similar to the one in Youji Yamada's movie series Otoko wa Tsurai yo.

The parallel made between The Spider's Thread and the narrator who hoped to use people's misery for his own gain without facing any consequences is a way for Tsuge to show that he doesn't aspire for more fame or money.

Back in the magazine Yagyou with Incident, this story show a strong bond between the two main protagonists that are united against the outside world. Their isolation is shown by never putting them in the same pannels as the other characters. 20 years later, Tsuge will relate the stormy relationships he had in the neighborhoods he lived in:

"As of today, I am still repulsed by society because it tries to exclude everything that is different or eccentric. The more people lack independance and individuality, the more they will try to fit fantasized social norms and persecute and ostracize those that are outside this group"

Similarly to A view of the seaside, Inn of the Withered Field gives a huge importance to the scenery and tries to imitate Edo-era etchings. Tsuge uses the early Hakaba Kitarou comics for the appearance of his main character and once again shows his love for spontaneous persons living their lives as they see fit without asking themselves too much question in the character of Iwao. A parallel is drawn between the lives of these two: one is a comic writer who dreams of living in the countryside while the other lives in the countryside and dreams of becoming a comics artist. Their growing frienship is interrupted by the apparition of the pragmatic wife who is here to hold up the whims of her husband, a regular motif in Tsuge's bibliography.

Yoshio's Youth was drawn at the same time as Inn of the Withered Field without any magazines in mind. This long story is refused everywhere and Tsuge comes to the realization that being praised by influencial intellectuals doesn't necessarily means getting all powers as a mangaka. He's 37 and it's the final straw: "I felt like the world of manga wasn't the same and I was ready to change career for real"

He will move out and open a coffee shop in front of the Ogikubo train station but gives up after 2 months because it ends up being too complicated. Yoshio's Youth will finally be accepted in Manga Sunday and be published in 3-part.

This story tells about his early days as an artist and he mentions the joy he had taking his inspiration from Kouji Uno's writing style:

"I found in his novels and unexpected charm that I hadn't felt in anything I had read before that. Everything is so carefree and Kouji Uno spends a lot of time writing details about unimporant things. I tried to find back this way of writing slowly and this old-fashioned but refreshing style with my story. Everything that happens in Yoshio's Youth is based on personal experiences"

Tsuge's describes his meeting with Akira Okada, his first mentor, with who he will learn about coffee, classical music and the joys of public baths.

It's one of the rare cases where Tsuge draws spontaneously, with a geniune will to draw but the lack of positive reception will break this short spurt of enthusiasm and the last few pages implying that the whole thing was about his loss of innocence before struggling to be successful are also a premonition of the most troublesome times Yoshiharu Tsuge will go through after that...

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The fifth anthology is also the fifth one chronologically and contains stories going from April 1975 to January 1981

Chapters included are:

Commoner's Inn (Shomin Onjuku (庶民御宿) Manga Sunday 1975-04)

A Room for Boredom (Taikutsuna Heya (退屈な部屋) Manga Sunday 1975-10)

Caught by the Night (Yoru ga Tsukamu (夜が掴む) Manga Sunday 1976-09)

Part-time Job (Arubaito (アルバイト) Poem 1977-01)

Life at Cape Komatsu (Komatsu Misaki no Seikatsu (コマツ岬の生活) Yagyou #7 1978-06)

The Deadly Dried Squid Technique (Hissatsu Surume Katame (必殺するめ固め) Custom Comic 1979-07)

Outside Inflation (Soto no Fukurami (外のふくらみ) Yagyou#8 1979-05)

Yoshibo's Crime (Yoshibou no Hanzai (ヨシボーの犯罪) Custom Comic 1979-09)

The Fish Stone (Sakana Seki (魚石) Big Gold #4 1979-11)

Hands at the Window (Mado no Te (窓の手) Custom Comic 1980-03

Aizu Fishing Inn (Aizu no Tsuri Yado (会津の釣り宿) Custom Comic 1980-05)

Playful Days (Nichi no Tawamure (日の戯れ) Custom Comic 1981-01)

Yoshiharu Tsuge repeated it all throughout his career, for him creation is more of a constraint than a necessity: "If only I could live without having to draw, but alas, I need money in order to live; and to draw again when I run out of money". The man who gained fame in 1968 with "Screw-style" slows considerably his publication rate from the 70s onwards. The royalties coming since he left Garo are constant and allow him to publish stories only once in a while. Severe personnal problems will force him to slow down his rythm even more in the second half of the 70s. Going through a midlife crisis, inspiration doesn't come as easily and he has to reuse the formulas that made hime famous: travel logs, tales from everyday life and onirical stories, without rehashing them despite his chaotic emotionnal state, he still pursues a form of authenticity.

Published in Manga Sunday in April 1975, "Commoner's Inn" signs the return of his travel logs with the main difference being that its main character is for the first time accompanied by a sidekick and brings back the comical dynamic of "Time of the boarding house" to make his story progress. The sex scene he drew to appeal to the readers is longer than usual. Proud of this result, he mentions in an interview that the secret to a well made drawing is to thrill the imagination.

"A room for boredom" is the last story to showcase the couple from "Incident". Once again, his desire to escape are hindered by his wife who represents for him everything he tries to escape: his mother.

-In writing

Other Links:

Instagram - Ryan Holmberg on Maki Fujiwara's picture diary

Youtube - Interview of Ryan Holmberg on The Swamp

Gallery from the Angoulême exposition on Tsuge

Posted by

Robinne

| Jun 27, 2019 2:18 AM |

1 comments

|

Leosmileyface | Mar 16, 2021 11:09 AM

Highly informative, I really appreciate this write-up! :)

|

|