Dec 25, 2020 10:42 AM

‘Koe no Katachi is dangerous because it is exploitative’

Anime Relations:

Koe no Katachi

‘Koe no Katachi is dangerous because it is exploitative’

… is the first line of Detective’s infamous review. They argue the film sacrifices realism for exploitative sympathy-bait, assuming KyoAni is motived by commercial gain rather than compassion for the deaf. His review represents the major criticisms of the film, shared by fellow MAL users and film-critics alike. To decide whether these criticisms are valid, here I will explore each side of the argument independently. Please note that I am not deaf nor know anyone who is, so my opinions are based on research and not prior experience.

For

The film exploits deafness as a plot device to earn sympathy from the viewer. Shouko is not a person who is understood through the mutual human experience, rather an object to pity, akin to an injured puppy. The film showcases her struggles with deafness to emphasise her pitiful nature so the audience can feel better about themselves through her vicarious triumphs against adversity. Koe no Katachi has no intention to accurately portray the deaf experience, only to highlight the moments of maximum suffering to bolster her pitifullness. The creators take the moral high ground because they are representing disabilities, but are ultimately motivated by monetary gain, facilitated by fans who are too blinded by their sympathy for disabled people to realise the nefarious means in which their pity reaction is achieved.

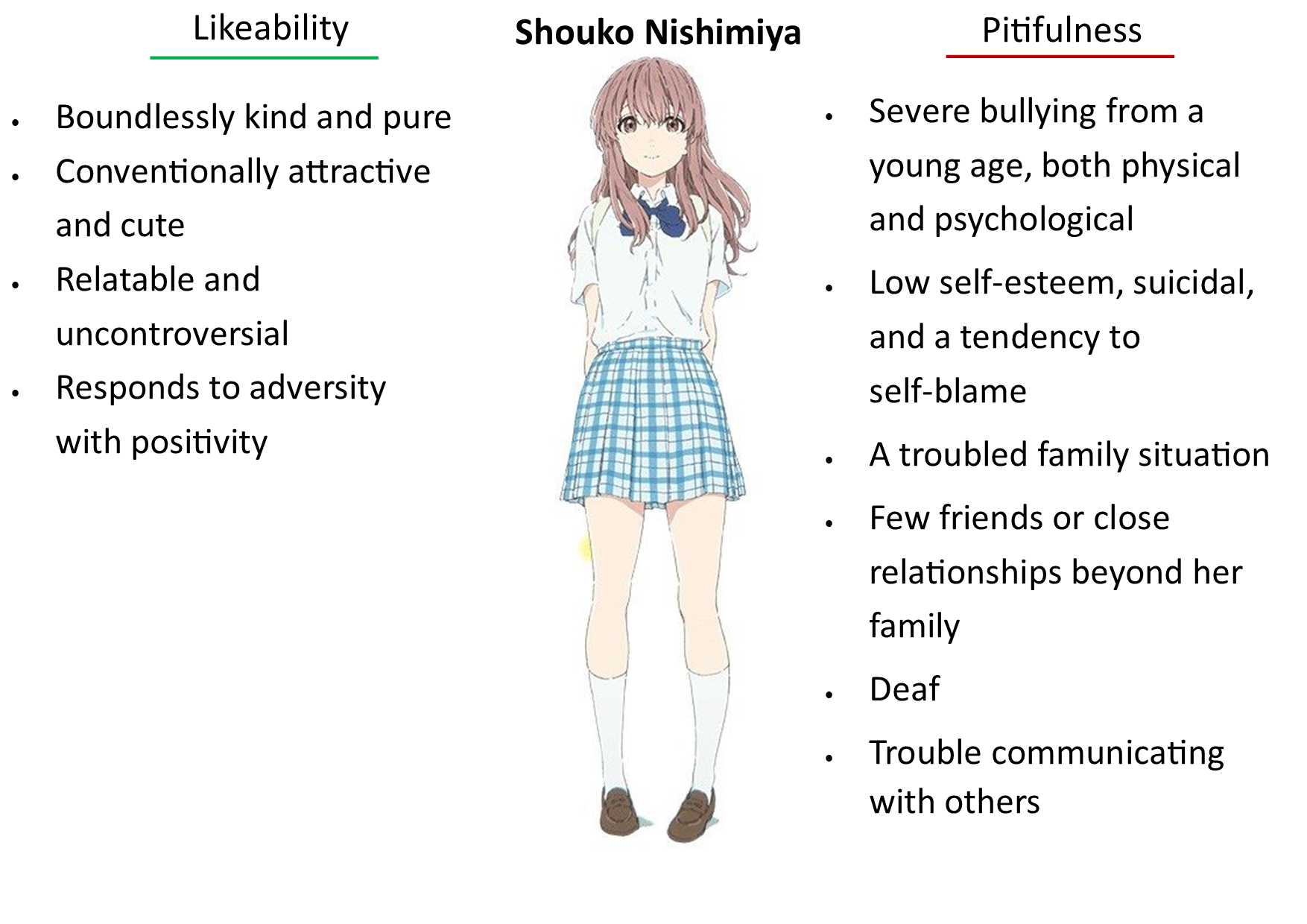

Put in PPD terms, Shouko’s character is designed to emotionally manipulate the audience; her likeability is contrasted against massive undeserved suffering. Presenting some evidence:

Such engineering of personalities is a twisted way to sell a story based on sensitive issues such bullying and suicide, particularly when featuring disabilities.

These traits reveal that Shouko's personality is built around her deafness, either directly or as the initial trigger. This perpetuates the notion that disabled people are defined by their disability - take away her deafness, and Shouko has no personality, nor hobbies, nor likes/dislikes – she exists to parade her condition. Capitalising on these characteristics is weaponization of moe and deafness.

Koe no Katachi is ‘inspiration porn’, the objectification of disabled people for the benefit of able-bodied audiences. Sites like Facebook and Instagram are rife with short consumable videos of disabled people overcoming adversity in motivating ways, inspiring the able-bodied to feel vicarious pleasure. In the same vein, Shouko is a symbol for her disability whose triumphs exist to please the viewer. She is an object who is tasked with overcoming the obstacles and roles which she is presented with, and the audience is invited to clap at her bravery rather than empathise with the person inside. As Detective puts ‘affection for things like this a wonderful human trait, but this work is dubious.’

To expand on the issue of designer personalities, Koe no Katachi must represent its deaf characters respectfully and realistically, especially as disabled representation is so sparse. The media is a powerful resource to challenge stigma and correct misinformation, so failure to do so may perpetuate unfair stereotypes of the disabled. Unfortunately, the film does exactly that - paints a dangerously narrow and arguably harmful image of deafness, pushing her most distinguishing characteristics to the forefront and further cementing the notion that disabled people are defined by their deviances from the norm.

Left: Momoko Kaeru ga Kikoeta. I wonder which protaginist is more popular

Would Koe no Katachi have been as wildly popular had Shouko been replaced by a mentally challenged, physical deformed boy? It is an uncomfortable reality that most audience members favour Shouko’s characteristics as an attractive vulnerable girl, thus making her easier to sympathise with. It is filmmaking convention to feature attractive characters, but Koe no Katachi’s intentions here are too transparent.

The most dangerous notion which the film perpetuates is that disabled people exist to be saved. Rather than solve her issues independently, Shouko embodies the damsel in distress trope, a female character (often attractive and likeable) who needs to be conquered by a man to relieve her suffering. Shouko is tailor made to this role through several characteristics:

• Reliance on sign language puts her in direct and unavoidable communication with Ishida

• Depends on and trust others quickly

• Lack of other social contacts make her easy to approach and befriend

• Lonely and need for support

These characteristics are not inherent to her disability, but they are inferred to result from her struggles related to deafness, pushing her in a vulnerable position for Ishida to sweep her away. This is a worrying conclusion – disabled people are somehow in need of saving, or as a romantic target to facilitate a dependent relationship. The film promotes this reading of the film – Shouya is a white knight self-insert for the audience to project themselves onto so they can vicariously save the damsel in distress. For Shouko to be so accepting of these advances – even blindly falling in love with the first person who shows her any attention - is a vulnerable characteristic which sends a dangerous message to those who want an easy way into a relationship.

These romantic advancements often involve grandiose gestures like learning sign language or risking one's life to save theirs – these extreme acts of kindness are condescending. It perpetuates the notion that romance can only be achieved though over-the-top showcases of bravery and commitment, wowing the woman into submission. The writing overuses these intense spontaneous events rather than an organic relationship progression, overshadowing Shouko’s role as a character and suppressing her development into a romantic target.

The in-film reaction to Shouko’s personality raises questions on how disabled people should be treated. Does her deafness grant her absolute goodness, such that anyone opposing her automatically becomes a villain? The film is quick to villainise Ueno and co in this respect, and while their actions are clearly unfair, the notion is that anyone who opposes Shouko is antagonised. Disabled people have interesting stories to tell, quirks, and virtues like anyone else, but it is up to the individual to find them likeable or not. The film takes away this option by thrusting purity upon her rather than a rounded character with all kinds of angles and rough edges. In other words, disability should not be a measuring system to determine anyone’s level of integrity when treating others.

Counter:

The ways in which Shouko reacts and internalises her experiences are unique to her and not inherent to her disability. The creators indeed selected the most marketable personality traits possible, but the underlying point here is that these traits do not derive from her deafness.

To punctuate this point with a comment on Detective’s profile by YukkoIsDead: ‘Nishimiya may be unbelievably, almost perhaps inhumanly, forgiving, kind, and a Mary Sue, but the truth is that such people exist. Who, because of their disabilities, or simply inferior qualities, try to make the best out of their situation by being meek and earnest. They may be too rare to believe in, but you better believe they exist, because I have seen such people with my eyes. She is a human, albeit nearly an impossibility, with needs and aspirations and flaws like everyone else.’ People who present with these personality traits may or may not result from deafness or even disability, but understand that these are normal methods to cope with adversity which deserve to be represented.

Shouko is not exclusively an object to be pitied, rather a character who can be empathised with directly. Able bodied viewers will never understand her difficulties as a deaf person, but one can empathise with how she responds to her hardships. Have you ever isolated yourself because you presume you are a burden on other people, or assume people-pleasing strategies to smooth out social interactions? These are not exclusive traits to the deaf experience and are thus available for everyone to identify with. It should be obvious, but the sentiment seems to have been lost to certain critics.

Shouko certainly possesses marketable qualities, but this represents a larger societal issue in which female leads must be attractive for the film to be commercially successful. It is an unfortunate reality that Koe no Katachi must participate in these paradigms to communicate its useful messages to a broad audience, but a necessity.

The definition of exploitation is to benefit from a resource at the expense of the resource, but should this negative impact be assumed by able bodied audiences without considering how deaf people feel about the film? A trip to reddit and various anime blogs demonstrates a resounding affection of the film from deaf audiences, often celebrating the realistic depiction of deafness and rare representation of the condition. For instance:

• The specifics of the bullying are said to be accurate, like tapping hearing aids, isolation due to social difficulties, and talking behind their backs

• People pretending to move their mouths (as to mimic speech) and treated as a plaything

• In a relational sense, being treated as a project or object of pity, or satisfying someone’s fetish of control and moral redemption

• Being overly apologetic because they are self-conscious of their speech difficulties

• Shouko’s phase of not wanting to use sign language to pretend she can hear/speak better than she can, as to not disappoint others

• The accuracy of the sign language, enhanced by KyoAni’s excellent hand animation

• The scene when Shouko realises Ishida’s presence through the vibration of the handrail (a detail I would have never noticed otherwise)

If for no one else, this film is rare representation for deaf audiences. That isn’t to say every deaf person likes or agrees with the notions the film presents, but it is a step in the right direction to include a more diverse and representative variety of stories in the medium.

Shouko is presented through Ishida’s perspective throughout the film, and thus her role and character presentation shift according to Ishida's opinion of her throughout. In the first act, she is an annoyance, someone who attracts undeserved attention because of her disability. After the time skip, she becomes someone to apologise to, a person to protect so Ishida can feel better about himself. Ishida falls into the white knight redemption archetype, but his attempts to execute his plans are forced and ineffective because he doesn’t consider Shouko beyond her disability or place in his memory, so Shouko is hurt by his awkward advances. It isn’t until the post hospital arc that Ishida realises that Shouko is a person beyond the roles he hoists upon her, and honest human communication with apologies and acceptances is ultimately how they connect, and he finally progresses.

In this sense, the film is aware of how the majority sees disabled people – as a project, as something to pity and needs help, and a way to make themselves feel better – because Ishida falls into these traps himself. The point of the film is to look past those misconceptions and connect with the person inside by treating them like anyone else.

Shouko’s internal suffering is not due to stupidity, rather what she believes to be logically true based on how people have treated her. She believes that her speech difficulties and hearing impairment causes others trouble. Most are nice enough not to let it show, but interact with enough people and you will learn the ways in which people recognise and are made uncomfortable by your awkwardness. Their shifty body language saying, ‘this person is difficult to interact with’ and the subsequent methods to end the conversation when they realise it’s too much trouble. This isn’t because they are terrible people, but because you are at fault, even if it’s unfair. Since your fault is a fundamental part of who you are, you do not deserve to interact with them. If you were normal, then they wouldn’t have to make the adjustments necessary to talk to you, nor would the people around you suffer for associating with an outcast.

Shouko’s line ‘I’m doing the best I can’, uttered in her fight with Ishida, sums up her reality. A hopeless existance who will never fit in like everyone else, so she does as much as she can for others to save them the trouble of interacting with her. This is prevailing opinion of self remains with her until corrected by Ishida at the end of the film. The ‘date’ scenes reveal this mindset - Ishida is forcing a friendship between them through organised trips, but the forced unease of his advances exposes the pity he feels for her. Shouko picks up on his intentions and recognises that his treatment of her results from her differences, and blames herself.

Along the same lines, Shouko falls for Ishida upon the smallest evidence that he cares for her. Living a life where she does not believe that others can love her, she clings to the few people who she deems dependable, even if a past bully, and looks to confirm their affection quickly – prompting the hurried confession. After all, she has no confidence that anyone else will accept them in the future.

I hope this has presented a balanced argument to the question proposed. This is less of an exhaustive opinion piece and more of a cluster of mine and other’s opinions, rattled off with little structure because it was a nightmare to write formally. Also, this has no relevance to Christmas, it just happened to be finished today.

Posted by

takara6

| Dec 25, 2020 10:42 AM |

Add a comment